From Penelope to Pussyhats, The Ancient Origins of Feminist Craftivism

On Subversive Uses of Women's Handicrafts Throughout History

The pussyhat has emerged as the most salient emblem of the Women’s Marches that took place in January as a response to the presidential inauguration of Donald Trump. The Pussyhat Project grew with such momentum that knitting supply stores began to run out of pink yarn. Aerial photographs of the massive crowds have a decidedly pink hue, and, following the marches, pussyhats graced the covers of Time and The New Yorker.

The pussyhat has not, however, enjoyed universal approbation. Camille Paglia was “horrified, horrified” by the hats, calling them a “major embarrassment to contemporary feminism” that denied marchers “dignity and authority.” Petula Dvorak similarly denigrated the hats as “she-power frippery.” Such dismissals of the pussyhat echo a longstanding tendency among some feminists to reject the traditional handicrafts of women, such as knitting, weaving, embroidery, and quilting, a criticism that springs from the feeling that they represent not the liberation but the oppression of women.

Embroidery inscribed by imprisoned suffragettes in Holloway Prison, 1912.

Embroidery inscribed by imprisoned suffragettes in Holloway Prison, 1912. Photo via Museum of London.

On the other hand, such denigration disturbingly participates in a long tradition of belittling women’s artistic pursuits, particularly those associated with poor women and women of color, which have rarely been afforded consideration as serious art. Moreover, it fails to consider the various ways in which women have transformed such crafts into tools of empowerment. Imprisoned suffragists in the early 20th century, for example, embroidered handkerchiefs to record not only their names but also the force-feeding they endured during hunger strikes. My own grandmother sold handcrafted quilts to help feed her impoverished family of 7 children in the rural South during the 1960s. American women long found creative expression and conversation (often dismissively termed “gossip”) in the quilting bee, a social custom memorialized in a celebrated work by Grandma Moses, who herself turned to painting only after arthritis made embroidery impossible.

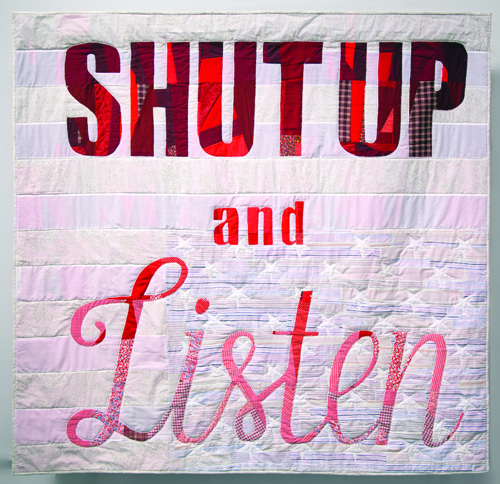

The pussyhat is part of a larger contemporary phenomenon known as Craftivism, which actively challenges the longstanding disparagement of women’s traditional art forms and has itself become a vehicle for feminist opposition. Craftivists run the gamut from hobbyist cross-stitchers urging us to “smash the patriarchy” to professional artists devoting painstaking hours to gallery exhibits. The Craftivist movement inherits a long tradition stretching back to the earliest history and literature of the West: Greco-Roman writers showed again and again how feminine art forms, particularly spinning and weaving, both segregated and subordinated women while also offering them an avenue for resistance.

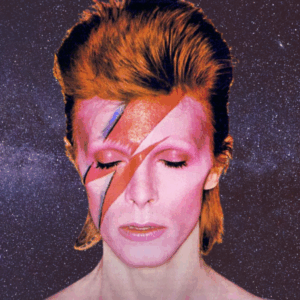

Jessica Wohl, White America, 2016.

Jessica Wohl, White America, 2016. Photo by Abdi Farah.

Woman, Get Back to the Loom: Weaving as Tool of Exclusion

The women of Homer’s epics (8th c. BCE) are told repeatedly to return to their weaving and stay out of the business of men. In the Iliad Andromache, wife of the Trojan warrior Hector, meets her husband on the city’s famous walls. She knows too well the toll of war; her father and seven brothers were killed in battle and her mother enslaved. She asks Hector to take up position in a less dangerous area of the battlefield. He replies, “Go home and tend to your own tasks, the distaff and the loom, and keep the women working hard as well. As for the fighting, men will see to that.” With Andromache silenced, Hector returns to the battlefield; he is killed and she enslaved.

In the Odyssey Penelope, still awaiting Odysseus’s return, overhears a bard singing tales of the Greek warriors’ homecomings. Descending to the suitors’ feast, she requests a different song, whereupon her teenage son Telemachus repeats Hector’s words to Andromache almost verbatim: “Go back to your quarters. Tend to your own tasks, the distaff and the loom, and keep the women working hard as well. As for giving orders (mythos), men will see to that.” Mythos here connotes public speechmaking, from which Greek (and later Roman) women were always excluded.

In these Homeric passages, men’s activities are dynamic and variable while women are meant to remain fixed in the interior of the house, engaged in the static occupation of wool-work. Wives who uphold these divisions become archetypes of marital chastity; Penelope has indeed come down to us as the paradigmatically chaste Greek woman whose fidelity to her husband withstands two decades of his absence.

In later Roman literature, spinning and weaving remain the orthodoxy for chaste wives, most famously Lucretia. In the version told by Livy (59 BCE-17 CE), Lucretia’s husband Collatinus enters into a competition with his cousins, one of whom is the prince Sextus Tarquinius; the contested point is which has the most excellent wife. Having found the other women drinking and dining, “they came upon Lucretia sitting in the middle of the house busily spinning” (Warrior). Her chastity cannot, however, protect her from sexual assault; Sextus later returns and rapes her, a violation to which she famously responds by killing herself so that no unchaste woman will ever cite her as a precedent for continued living.

Woman spinning; Attic red-figure lekythos, 480–470 BCE.

Woman spinning; Attic red-figure lekythos, 480–470 BCE. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The material record echoes this ideology. Countless Greek vases depict women busily spinning and weaving in the women’s quarters. Roman gravestones repeatedly commemorate the wool-work of women as synonymous with wifely chastity. One inscription from the 2nd century BCE celebrates a woman named Claudia. The summation of her virtues reads, domum servavit, lanam fecit, “she kept the house, she worked wool.” Another from the 1st century commemorates an Amymome as lanifica pia pudica frugi casta domiseda, “a wool-working, pious, modest, frugal, chaste, sit-at-home woman.”

Women’s Crafts and Crafty Women: Weaving as Resistance

Hesiod’s Works and Days (c. 700 BCE) records the creation of the first woman, Pandora, a punishment for men after Prometheus steals fire from Zeus. She is sculpted by the artisan god Hephaestus and taught weaving by Athena, patron goddess of wool-work. But Pandora exemplifies a more devious type of craft; the trickster god Hermes gives her a thief’s heart that she cunningly employs to drain the economic resources of her husband. Weaving here signifies woman’s ability to deceive, to swindle, and to emasculate. It is her cunning intelligence and intricate webs that make woman dangerous. The story offers justification for, in fact demands, the exclusion and oppression of the female sex. Despite the horrifying misogyny of Hesiod’s intentions, this story nonetheless evidences another possibility for woman’s craftwork: that it can challenge male authority and subvert the hierarchy that keeps her in check.

This link between cunning and weaving is clear already in Homer’s Odyssey, where Penelope finds herself precariously poised between marriage and widowhood. Facing pressure from her suitors to remarry, she has recourse to a famous trick:

They rush the marriage on, and I spin out my wiles.

A god from the blue it was inspired me first

to set up a great loom in our royal halls

and I began to weave, and the weaving finespun,

the yarns endless, and I would lead them on.

She promises the suitors that she will choose a new husband as soon as she finishes the burial shroud for Laertes, her father-in-law, but every night for three years she returns to the hall and unravels her handiwork. There is something peculiar about the fact that the suitors never catch on; it is instead her maids who inform the suitors of Penelope’s deceit. The woven tapestry becomes a text that only she and her fellow women can read, a discursive space that excludes men. This is one reason it contains the power to subvert.

“Despite the horrifying misogyny of Hesiod’s intentions, this story nonetheless evidences another possibility for woman’s craftwork: that it can challenge male authority and subvert the hierarchy that keeps her in check.”

Homer is of course no feminist. Penelope’s cunning intelligence offers her a means of resisting her suitors, but it also makes her a good match for her husband’s own mental agility. She complements rather than challenges him. The dangerous potential of her craft is neutralized by her use of it to reinforce Odysseus’s patriarchal authority. Odysseus in fact remains skeptical of his wife as he cautiously reintegrates himself into his house. His beggar’s disguise allows him to put her through a series of tests; only when he is certain no other man has been in his bed does he finally reveal himself to her. Even in faithful Penelope there is the lurking danger that she may outcraft him.

In Roman literature, Ovid’s Metamorphoses (c. 8 CE) repeatedly explores the links between weaving and defiance. One of its most gruesome stories is that of Philomela, who is taken captive and brutally raped by her brother-in-law Tereus, a Thracian tyrant. When she threatens to shout out everywhere the story of his crime, Tereus places her tongue in pincers and cuts it out, silencing her. She remains entrapped in a cabin in the woods, where he rapes her again and again for over a year. She turns to the loom to recover her lost speech:

Mute lips cannot tell. But grief has its own genius,

And with trouble comes cunning. She sets up

A Thracian web on a loom, and weaves purple signs

Onto a white background, revealing the crime.

Philomela smuggles the tapestry to her sister Procne through a female attendant. It is again curious that Tereus fails to detect this deception; the woven tapestry speaks only through and to women. The Women’s March pussyhat shares with Philomela’s web the ability to inscribe an act of sexual assault insofar as it makes a clear visual reference to Trump’s now infamous boast that he habitually “grabs” women “by the pussy.” Both the knitted hat and the woven tapestry ring out a cry of opposition.

But it would be wrong to read Ovid’s story as an unambiguous lament for Philomela’s plight; his epic, after all, contains one story after another of brutal rape. And her tale suddenly transforms to become an illustration of the impious violence of female vengeance. The sisters murder the young son of Procne and Tereus, cook his flesh, and serve him to his own father. Philomela’s capacity for craft is outdone only by her pursuit of vengeance. As Patricia Klindienst suggests in a landmark essay, we must fashion our own meaning out of Philomela’s story: “If the myth instructs, so does Philomela’s tapestry, and we can choose to teach ourselves instead the power of art as a form of resistance . . . We have now begun to recover, to preserve, and to interpret our own tales.”

Women spinning and weaving; Attic lekythos, c. 550-530 BCE.

Women spinning and weaving; Attic lekythos, c. 550-530 BCE. Photo via the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ovid’s most famous weaver is Arachne, who surpasses all women in wool-work. She boldly challenges Minerva, herself intent on demonstrating her fearsome power, to a contest of skill. Arachne’s tapestry is the work of an artist in her prime, and it finds a parallel in Ovid’s own “fine-spun” epic song. Like Ovid’s poem, it depicts the rapes of women, especially those perpetrated by gods. Minerva’s tapestry, however, also evokes Ovid’s text; it shows us, just as Ovid has, the might of the gods and the sufferings of those who challenge them. The story puts into competition two opposing views of art: one subverts established power and the other enforces it.

Ovid makes it clear that Arachne is the superior artist: “The golden virago, incensed at Arachne’s spectacular success, ripped the fabric apart with all its embroidery of celestial crimes.” Minerva violently strikes Arachne, then transforms her into a voiceless spider whose webs no longer have the power to articulate resistance. Outmaneuvered by such craft, the powerful have recourse only to brute force, but they cannot quell speech entirely: “All of Lydia buzzed with the story, which spread through Phrygia, too, and filled the world with talk.”

Ovid does not tell us how these talkers interpret the story, whether they draw the lesson of Arachne’s tapestry or Minerva’s. But the final act of defiance is achieved whenever anyone grants the win to Arachne; artist, object, and interpreter join together in an unruly alliance of which we can still be a part.

These stories were largely intended to caution men about the treacherous ingenuity of women; they were not originally written for the female eye. Yet women and their allies would do well to read them and unravel new messages. Women have honed such resistance through centuries of oppression by using its very tools. Rather than denigrate or reject these long-established feminine forms of art, we should remember them. Craft, cunning, art, coded speech—these are the weapons of the oppressed. As women’s hard-won rights grow increasingly eroded and the parameters of free speech more contested, we must always keep at hand the subversive power of craft.

Stephanie McCarter

Stephanie McCarter is Associate Professor of Classics at Sewanee: The University of the South in Tennessee, where she regularly teaches courses related to women and gender in Classical antiquity. She is the author of Horace between Freedom and Slavery: The First Book of Epistles and has written essays connecting antiquity to the contemporary world for Eidolon and The Millions. She is currently at work on a translation of Horace's lyric poems.