Frivolity, Death, and Milena Busquets

The Author of This Too Shall Pass is Trying to Find the Light

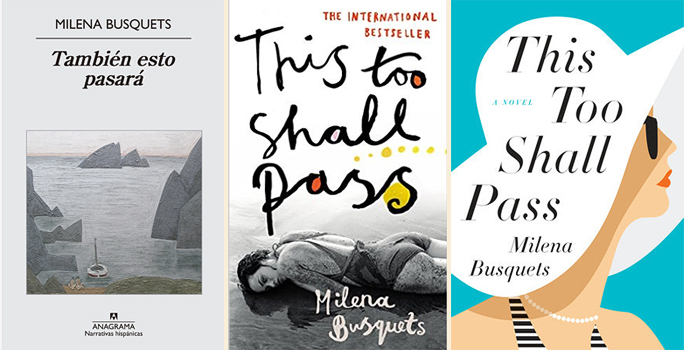

At first glance, This Too Shall Pass seems a perfect beach read. Light, short, set between Barcelona and the picturesque Costa Brava town of Cadaqués, featuring a woman reflecting on her life and relationship—or, as it’s popularly described, trying to “find herself.” Publishers in the English-speaking world seem to think so, at least: the book’s covers on both sides of the Atlantic feature either a young, half-naked woman lying dramatically on a beach (in the UK version), or an illustration of a Breakfast at Tiffany’s-style woman wearing pearls, sunglasses and an elegant sun hat (in the US).

“It’s weird, isn’t it,” laughs the novel’s author, Milena Busquets, as we chat about how book marketing works in mysterious ways. “My friends were like… ‘She’s got a great butt, but what is this?’” But she’s fine with it all—she just wanted to tell her story—or rather, Busquets tells me, she felt the uncontrollable urge to write the book about a year after her mother died. Labeled as “summery,” “sexy,” “cool” and “refreshing,” this, her second novel, is actually an exploration of the grief that shattered her after her mother died—masterfully interspersed with love, sex and a fierce thirst to live in a way that hooks you as a reader, keeps you going, and leaves you not knowing what hit you.

This Too Shall Pass (translated into English by Valerie Miles) was the “hot book” at the Frankfurt book fair two years ago, where, before it was even published in Spain, 29 international publishers had purchased its rights. Now, sitting in a Greek cafe in London, as the book has recently hit stores in the English-speaking world, Busquets observes the gigantic literary success it’s already had in Spain—and part of the continent—from a safe distance. Her stance on it feels partly detached, partly amused, partly melancholic.

It’s not like she had much interest in being back in the literary world, having had more than her fair share of it growing up. For the daughter of one of Spain’s most prominent editors of the second half of the 20th century, Esther Tusquets, it wasn’t uncommon for artists, authors and intellectuals to casually drop by the house and drink wine with her parents when she was a kid—Julio Cortázar himself wrote to her mother congratulating her on Milena’s birth, and hoping for the newborn “all the fish and clouds and chocolate she wishes for.”

Busquets seems, however, unimpressed with Barcelona literary circles, and hasn’t made any efforts to become part of the scene. She’s always been “bored” by the parties everyone attends. “This book talks a lot about freedom, and it’s really important to choose, in life. Sometimes things are just handed to us, and even if you have been fortunate, there comes a moment where you have to choose them. And I realized I hadn’t chosen the publishing world, it had been with me since the crib—and I wanted to choose it. So I left [after having worked in a publishing house with her mother]. And now I’ve done this, and no one can say or think it’s because I’m the ‘daughter of…’”

As with the cover of This Too Shall Pass, it quickly becomes clear that, with Busquets, you shouldn’t let the package fool you. She keeps her distance behind a casual bourgeois demeanor—a very particular kind, from a very particular Barcelona intellectual bohemia—but I’m more interested in how and why she wrote such a gut-wrenchingly honest novel. The book, most of which is unashamedly autobiographical, is part elegy, part love letter to her mother, and part evocative summer tale. The coastal village of Cadaqués, known for being frequented by the likes of Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp, takes center stage as protagonist Blanca travels to the town of her childhood summers to deal with her mother’s death—bringing her girlfriends, kids and two ex-husbands along.

There’s a lot of drama, sex, and fun, and the cocktail is skillfully delivered. Blanca deals with grief by trying to live fast, wildly, freely, childishly. She uses sex as escape and as a way of being loved (“I think it’s a actually pretty romantic book,” Busquets says). The Spanish newspaper El País summed up the emotions This Too Shall Pass portrays as the “sad joy of living.” Fellow Catalan author Sergi Pàmies also put it succinctly: “The first impression of the tone is that of a French-style comedy with moments of light snobbery. But don’t be fooled: once you bite the hook, the text will get stuck to your palate, it will drag you along, making you taste the salt, the blood, the horizon and the abyss of a sea…”

“To the best of my knowledge, the only thing that momentarily alleviates the sting of death—and life—without leaving a hangover, is sex,” says Blanca early on in the novel. Busquets is aware of her character’s frivolity. Not just when it comes to sex, lovers, or drugs, but also because of the many casual comments about, for instance, fridges stocked with only cheese and wine. “It’s a book about death, but there is a lightness, a will to live, a vital impulse which is youthful, almost childlike,” she says. “The wine, the friends, the sea, the men: they can be considered really light things, but they’re also pretty deep, aren’t they? I’m not sure we have deeper things than this.”

“I don’t agree with the idea that writers need to only talk about philosophical and very serious topics, very transcendental, and in a very cold way,” she adds. “I think if Oscar Wilde was alive today in Spain, he’d be considered frivolous.” Frivolity, she argues, is not the same as superficiality: “Really important things can be said from very privileged and very light positions. I think Woody Allen is at his best in the lightest comedies—and so is Almodóvar. When he tries to get serious, you lose all the essence of what he is.”

“Frivolity is an instrument for me to carry myself through the world,” she argues. “For other people it’s a sense of humor, or power, or seriousness. Lightness works better for me. I also think this is down to education, of a certain intellectual bourgeoisie, of having to never bore others, keep up appearances, be pleasant… It’s very… of Barcelona.” As someone who grew up in the same city, I concur.

Busquets feels nostalgic for what is known as the Gauche Divine [French for the “Divine Left”], the intellectual bourgeoisie that emerged in Spain in the 1960s and 70s as a reaction to the hippy, student, and revolutionary movements in the UK, France, and US. The country was still under Franco’s horribly oppressive dictatorship, and desperate for freedoms (of all kinds). A joie de vivre, sexual liberation included, swept through its artistic and literary scenes. It was fascinating to grow up as the daughter of that movement, she says: “I saw in it a way of having fun, of being happy, of saying what they thought—I liked their approach, that you are free and you can take control of what you’re going to do with your freedom, which is something we often take for granted in the Western world.” Growing up close to writers like Jaime Gil de Biedma, Ana María Matute, or Juan Marsé was educational: “Even as a little girl who wouldn’t read them for many years, I liked them; I’ve always liked adults. I liked sitting in a corner observing them, I was never bored by that.”

This “lightness in sadness” approach has seen her work often compared to François Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse, with which she sees similarities—but she would prefer being linked to Colette or Proust. This approach works for her: “Not letting panic spread. Because panic is about to spread very often, in life. It could spread all the time.”

I ask her whether she exposed too much of herself in this novel. “The thing is, once you’re actually writing something, the only thing that matters is the story. And your only loyalty must be to the story; it’s your only boss.” In that sense, “cheating” (like “trying to make Blanca less selfish, more attractive, so to speak”) would be to “betray the reason of the book.” “Prudishness is useless, to make literature. Or self-fiction. Or anything artistic, really.”

Busquets says she had “never” even contemplated writing about her mother before this. “She was such an important presence and such a close person to me, that you never think you’ll write about something so near you. And suddenly, a year after her death, I just saw it crystal clear. I just thought I wanted to tell the love story between a mother and her daughter.” One day, she says, she sat at the kitchen table after taking her sons to school and wrote the first chapter. “What’s sad is that she had to be dead. I don’t think I would have been able to do it with her alive.” She will add, later on, that the book’s success feels tainted: “A lot of people have read it, but the only person that should, will never.”

After all this, This Too Shall Pass hasn’t proven therapeutic. “Even if the book has worked and people have liked it, my mother is still dead. My mother is not in London with me, like she’d been millions of times [Ed. note: they came to the city to scout for new children’s books]. My mother can’t share this, doesn’t know what’s happened with the book… So it feels like a failure within the success.” But she never expected, she says, for literature to do that. “Literature might heal others. I feel like I’m healed by other people’s literature: Proust and Chekhov heal me. But with yourself, writing is not the healing cure; reading is.”

Marta Bausells

Marta Bausells is an editor-at-large for Literary Hub. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, Electric Literature, Literary Review and other publications, and she is the creator and former editor of the Guardian Books Network. She lives in London and originally hails from Barcelona. You can find her on Twitter @martabausells.