Five Books Making News This Week: Death, Dystopia, and Depression

Happy Valentine's Day!

“There has never been a more important time for writers to assemble,” Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Teheran, told a packed ballroom at this year’s Associated Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) conference in Washington, D.C. “Literature and art not only resists the tyranny of man, but they also resist the tyranny of time,” she noted in her keynote address. On Friday, a record audience turned out for a reading and conversation by two of the our era’s most influential authors, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Ta-Nehisi Coates. (The crowd of 3,600 overflowed two ballrooms, triggering a video follow-up session for those who couldn’t get in on Saturday afternoon.) Saturday night, as one of a series of protests, hundreds of writers and poets gathered within sight of the White House, with poet Ross Gay reading, “I am a brick in a house that is being built around your house” and Carolyn Forche reading Walt Whitman’s “This Is What You Shall Do.” And at the AWP bookfair, there were spontaneous readings (#BlackPoetsSpeakOut), advocacy (#ThankYouNEA), and an #IdissentDoyou postcard campaign.

Margaret Atwood’s prescient novel A Handmaid’s Tale spikes, George Saunders’ first novel arrives with a splash, a century-spanning saga tells the story of Korean outsiders, Daphne Merkin’s memoir captures depression, and the Mountain Goats frontman and National Book Award finalist is back with a dark and spooky novel.

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985, hit number 1 on Amazon this week. Sales have soared 200 percent since the election, and there was another bump after the trailer for the Hulu version, launching in late April, aired during the Super Bowl.

“The Handmaid’s Tale depicts an America collapsed into a theocratic dystopia called Gilead,” notes Petra Mayer (NPR). “It’s a place where women are brutally oppressed. They’re forbidden to read and forced to bear children for the ruling class. For many readers, that story is suddenly relevant.” (Atwood even shared with Mayer her predictions for the next best form for speculative fiction.)

“You are seeing a bubbling up of it now . . . It’s back to 17th-century puritan values of new England at that time in which women were pretty low on the hierarchy,” Atwood told Reuters in Havana during the Cuban International Book Fair, when asked about the resurgence of interest.

George Saunders, Lincoln in the Bardo

A widely cherished and honored short story author takes on a novel, focusing on President Abraham Lincoln’s grief after the death of his eleven year old son Willie I 1862. The response from critics? Glowing.

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) likens Saunders’ novel to “a weird folk art diorama of a cemetery come to life.”

Picture, as a backdrop, one of those primitively drawn 19th-century mourning paintings with rickety white gravestones and age-worn monuments standing under the faded green canopy of a couple of delicately sketched trees. Add a tall, sad mourner, grieving over his recently deceased son. And then, to make things stranger, populate the rest of the scene with some Edward Gorey-style ghosts, skittering across the landscape—at once menacing, comical and slightly tongue-in-cheek.

“The souls crowd around this uncanny child,” writes Colson Whitehead (New York Times Book Review). “In the midst of the Civil War, saying farewell to one son foreshadows all those impending farewells to sons, the hundreds of thousands of those who will fall in the battlefields. The stakes grow, from our heavenly vantage, for we are talking about not just the ghostly residents of a few acres, but the citizens of a nation—in the graveyard’s slaves and slavers, drunkards and priests, soldiers of doomed regiments, suicides and virgins, are assembled a country. The wretched and the brave, and such is Saunders’s magnificent portraiture that readers will recognize in this wretchedness and bravery aspects of their own characters as well. He has gathered ‘sweet fools’ here, and we are counted among their number.”

David L Ulin (Los Angeles Times) concludes, “Life is chaos and history a story, and even the greatest of our leaders are merely humans, after all. The recognition sits at the center of Lincoln in the Bardo, which is a book of singular grace and beauty, an inquiry into all the most important things: life and death, family and loss and loving, duty and perseverance in the face of excruciating circumstance.”

Min Jin Lee, Pachinko

Min Jin Lee’s second novel is a multigenerational saga of a Korean family that spans most of the 20th century. Critics compare her to Thomas Mann and Dickens.

Jean Zimmerman (NPR) writes, “We are in Buddenbrooks territory here, tracing a family dynasty over a sprawl of seven decades, and comparing the brilliantly drawn Pachinko to Thomas Mann’s classic first novel is not hyperbole. Lee bangs and buffets and pinballs her characters through life, love and sorrow, somehow making her vast, ambitious narrative seem intimate.”

“Lee is an obvious fan of classic English literature, and she uses omniscient narration and a large cast of characters to create a social novel in the Dickensian vein,” writes Steph Cha (USA Today). “Her protagonists struggle with the whims of history, with survival and acceptance in a land that treats even native-born Koreans as foreigners . . . ”

“Pachinko is about outsiders, minorities and the politically disenfranchised,” notes Krys Lee (New York Times Book Review). “But it is so much more besides. Each time the novel seems to find its locus—Japan’s colonization of Korea, World War II as experienced in East Asia, Christianity, family, love, the changing role of women—it becomes something else. It becomes even more than it was. Despite the compelling sweep of time and history, it is the characters and their tumultuous lives that propel the narrative.”

Daphne Merkin, This Close to Happy

The New Yorker writer and author’s frank and vivid memoir of her lifelong experience of clinical depression gathers accolades from critics.

“This Close to Happy is about living despite the persistent desire to die,” writes John Kaag (Wall Street Journal). “I will not be the last to thank Ms. Merkin for resisting this desire long enough to give us what is one of the most accurate, and therefore most harrowing, accounts of depression to be written in the last century.”

Merkin “narrates what happened and how it felt to her,” notes Andrew Solomon (New York Times Book Review). “And she does so with insight, grace and excruciating clarity, in exquisite and sometimes darkly humorous prose. The same tinge of self-aware narcissism that makes the book at times so annoying makes it finally triumphant. Merkin is unlikely to cheer you up, but if your misery loves company, you will find no better companion. This is not a how-to-get-better book, but we hardly need another one of those; it is a how-to-be-desolate book, which is an altogether more crucial manual.

Adam Kirsch (The Tablet) calls Merkin’s memoir “a hybrid of memoir, case study, and confession, which joins such classics as Kay Redfield Jamison’s An Unquiet Mind and Andrew Solomon’s The Noonday Demon in the contemporary literature of depression.” What distinguishes Merkin’s book, he adds, “and gives it an alarming power, is her recognition that depression is not something that once happened to her . . . , an experience she can now look back on with understanding.” For Merkin, he adds, “by contrast, depression is something that emerges from within, the medium in which she lives. She experiences it as ‘a yawning inner lack—some elusive craving for wholeness or well-being.’ Writing about a lack is difficult, and perhaps no one has ever captured exactly what it feels like to be depressed, simply because one can’t describe a negative. Merkin avoids this problem by writing less about the feeling of depression than about its causes and its remedies. What, she asks, made her so miserable? And what happens when she tries—through therapy, medication, or hospitalization—to cure that misery?”

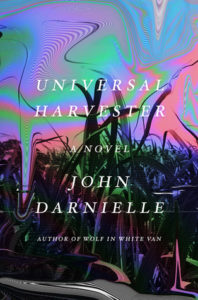

John Darnielle, Universal Harvester

“I envy the Willa Cathers who can go, ‘Look, my story can stand by itself,’” the Mountain Goats frontman and National Book Award finalist (for his first novel, Wolf in a White Van) tells PW’s John Maher. “Cather is so non-pyrotechnic. She’s like Sarah Orne Jewett. It’s just the force of clear, lucid prose, and characters who have flesh on their bones. And that’s the stuff I read for inspiration. I want my characters to feel like they’re people.” Darnielle reads from the new novel here.

Manuel Roig-Franzia (Washington Post) explains:

Something spooky is happening in Nevada: Disturbing scenes are mysteriously being spliced into the films that customers rent at the local Video Hut. Jeremy, a clerk at the video store, is reluctantly tugged into the search for the provenance of these altered films, a quest that becomes an unhealthy obsession for the store owner . . .

If Darnielle had confined Universal Harvester to untangling the story of the altered films, he would have written a perfectly acceptable creepy mystery. Instead, he produces a much richer work that—without giving away too much—takes a long pause from the video mystery to delve into a poignant, multigenerational saga of religious obsession and its shattering consequences.

“Rendered in hyper-realistic prose, the novel unfolds slowly, and Darnielle makes the mundanity of small-town life seem as terrifying as the disturbing films,” writes Eric Farwell (Bookforum).

Abram Scharf (MTVNews) points out that Universal Harvester is “a quiet story of grief with the trappings of a Stephen King suspense-thriller—the first book through which Darnielle has really spun a yarn. His other major fictional works, Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality (a 33 ⅓ series entry themed around the band’s 1971 album) and Wolf in White Van, were both extended character studies of troubled young men, focused more on following the narrators’ fragmented thoughts than crafting a traditional narrative arc. If adapted for the stage, either could make for a brilliant one-man show. Universal Harvester, on the other hand, is cinematic, action-driven. Its characters are constantly on the move, speeding toward destinations they fear will hold ‘scenes of unspeakable devastation and loss,’ and Darnielle seamlessly transfers their dread straight into readers’ hearts.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.