Five Books Making News This Week: D.C., The Internet, and Helen Gurley Brown

Jennifer Close, Virginia Heffernan, Brooke Hauser, and More

The anniversary of the publication of Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, which sold 1.6 million copies to top the 2015 U.S. best seller list, passes quietly, the sound of the crush of critics vying to define the novel’s effect on her legacy a distant roar. Attica Locke’s Pleasantville wins the Harper Lee Prize, endowed by Lee, who died in February, to honor work that “illuminates the role of lawyers in society and their power to effect change.” The National Endowment for the Arts’ Big Read program shifts focus toward books written since the NEA was founded 50 years ago. For 2017-2018, this means downplaying To Kill a Mockingbird, a perennial on the list, and adding work by Ron Carlson, Louise Erdrich, Joy Harjo, Kelly Link, Celeste Ng, Claudia Rankine, Kevin Young, and Alejandro Zambra, among others. Two biographies of Helen Gurley Brown flash back to the original Sex and the Single Girl, Jennifer Close publishes a satiric political novel on the eve of the party conventions, Virginia Heffernan presents the Internet as “the great masterpiece of human civilization,” and VICE fiction editor Amie Barrodale publishes a first story collection.

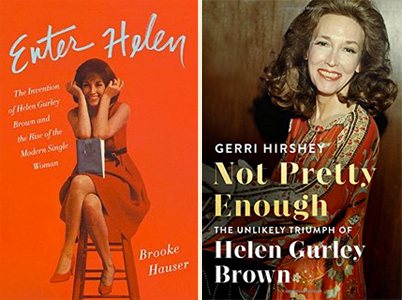

Brooke Hauser, Enter Helen and Gerri Hirshey, Not Pretty Enough

Two books about Helen Gurley Brown, legendary Cosmo editor, arrive at the same time, inspiring twin reviews.

“These two biographies matter precisely because Brown’s life and career anticipated the tensions that countless women are talking about now,” writes Moira Weigel (New York Times Book Review). “She offered a blueprint for success in a sexist world, telling readers how to game a system that was set up to exploit them. Was this the right approach? Whatever your answer, this is the same debate we are still having about the most powerful women in America, from Hillary Clinton to Beyoncé.”

Lorrie Moore (New York Review of Books) includes Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl and Jean Baer’s 1968 The Single Girl Goes to Town in her review, and concludes, “If Hauser’s biography sometimes reads like a screen treatment about making a glamorous life (her epigraphs are often movie quotes, particularly from Marilyn Monroe films, and she uses “Cut to” as a transition; photos, including one of the Browns’ grave in the Ozarks, are affixed),Hirshey’s book—once it gets past its bitter complaint about the Hearst Corporation’s virtual gag order on quoting Brown’s office memoranda—is a bit more like a novel in its attention to narrative tension and pacing and smooth writing. Moreoever, Hirshey cleverly transforms her final pages into something akin to an oral history, with several of Brown’s good friends—from the playwright Eve Ensler to Barbara Walters—chiming in.”

Jennifer Close, The Hopefuls

A former Conde Nast editor whose husband worked on the Obama campaign writes a roman a clef that has D.C. laughing.

Ron Charles (Washington Post) calls it “a hilarious gripefest about what it feels like to be caught in the gravitational pull of Washington.”

For you, the haters of D.C. who were dragged to the capital by spouses or necessity or mistaken idealism, here, finally, is a novel witty enough to match your secret loathing—and tenderhearted enough to make you realize how much you love this damned cesspool after all. Close’s narrator, Beth, settles into their new apartment off Dupont Circle and tries to enjoy herself, but their new acquaintances don’t make it easy. “We went to a dinner party,” Beth says, “where everyone—I swear to God—went around the table and announced their level of security clearance.” She tries to adjust, she tries to be positive, but she can’t help it: “I hated everything about D.C.”

Isabella Biedenharn (Entertainment Weekly) focuses on Close’s descriptions of political charisma. Jimmy Dillon, the “charming Texan” at the novel’s center, “absolutely has it: that golden magnetism that makes you wonder what it would be like just to stand next to him, if only for a second,” she writes. “Close, whose husband worked on Obama’s campaign, uses her knowledge of this world—and her experience as an outsider—expertly.”

Virginia Heffernan, Magic and Loss

Heffernan, a journalist and cultural critic, examines the Internet as a massive masterpiece of realist art. “As an idea, she writes, “it rivals monotheism.” In a reading at the Googleplex (Talks at Google), Heffernan describes her first viewing of the pioneering 2006 Fun Two “Guitar” video. “YouTube was like discovering a lost civilization,” she says. Critics find her new book provocative.

“Some of the most engaging parts of the book,” writes Mark O’Connell (Slate), “are the broadly autobiographical sections in which she reconciles the apparent contradictions of her own dual identity as both an early adopter of networked technology and a literary academic. And as someone who went from having Henry Louis Gates Jr. as a thesis adviser to writing clickbait for Yahoo News—work she memorably refers to as ‘Go-Gurt journalism’—she seems pretty well-positioned to write just this sort of book. Her intention is to examine the internet as a vast cultural artifact, one that she believes challenges the pyramids, the novel, the nation state, even monotheism—looming above them all as ‘the great masterpiece of human civilization.’”

“Heffernan aims to do for online life what Susan Sontag, Marshall McLuhan, Lester Bangs, and Pauline Kael did for the fields of photography, media, music, and film,” writes Anna Wiener (The New Republic).

She wants to give the internet a poetics—a vocabulary for appreciating its texture, its tones. Drawing on literary theory and cultural criticism, Heffernan seeks to “make sense of the Internet’s glorious illusion: that the Internet is life.” The web, she argues, is a masterpiece on par with “the pyramid, the aqueduct, the highway, the novel… the radio, the realist painting, the abstract painting,” etcetera. Just as each of these inventions changed the way we relate to one another and the way we express our humanity, the internet too is a social force, a locus of new cultural values. Like any social triumph—especially one in a phase of rapid development—it bears critical inquiry and investigation.

Louis Menand (The New Yorker) has quibbles. “Heffernan is smart, her writing has flair, she can refer intelligently to Barthes, Derrida, and Benjamin—also to Aquinas, Dante, and Proust—and she knows a lot about the Internet and its history. She is good company. But she has trouble extracting an aesthetics from the mishmash of information, entertainment, commerce, and distraction that is the Internet.”

Heffernan’s strength, notes Sara M. Watson (Columbia Journalism Review): “She plants her criticism firmly in subjective experience.”

We may or may not share her obsession with perfume forums or #freeskip Twitter campaigns, but we learn to read the internet for ourselves through her example. Heffernan gives us a vocabulary and a model for understanding our feelings, our concerns, our joys, and our fears about technology. Though Heffernan succeeds at demonstrating how one might read the internet as art, she does so mostly by example. Readers walk away understanding how Heffernan reads the internet, but we have to read between the lines to gather tools to carry on that critical work for ourselves.

Amie Barrodale, You Are Having a Good Time

A first short story collection from the fiction editor of VICE.

“While these stories aren’t interwoven, precisely, they often echo each other in odd, deliberate ways,” notes Carmen Maria Machado (NPR). “Not just the themes (affairs, Buddhism, therapy) but specific images that repeat and reference each other: waking up to strings of text messages or emails; calling or otherwise communicating with people across vast time-zone differences, things happening at 3 a.m….This uncanny repetition only adds to the collection’s unsettling mood. There is a fascinating grotesqueness here, from the mean, broken, oblivious characters to the funny, ugly scenarios they’re placed into. Even the structures of the stories are disconcerting: They always open so deep midscene—so breathlessly ready to go, so breathlessly already going—it’s disorienting, like a film that starts with a character in midfall off a cliff.” But, she adds, “the grotesqueness is also cut with moments of beauty.”

Barrodale’s “stark and cutting” stories, writes Nicholas Mancusi (New York Times Book Review), “grapple with our failure to communicate, and investigate not merely the woeful inefficiency of language itself (although that’s bad enough) but also the inherent impossibility of truly understanding another person’s internal state.”

The book’s power, he concludes, comes from “Barrodale’s ability to distort and project the familiar into something new, like a visual artist playing with shadows cast on a gallery wall.”

Nina Sparling (The Rumpus) focuses on the collection’s limits: “Each of the stories deals, generally, with thirty-something Americans in bad relationships. Reading about them is like being a friend’s date to a dinner party among her close friends: Everyone sees the stranger in the room but continues the gossip about their lovers, mothers, and prescriptions as if the new arrival understood by default. No effort is made to show the stranger this unfamiliar social world. Ultimately this collection is about how a small slice of people—wealthy, creative types, some writers, some actors, some musicians—deal with one another.” The customs and particularities are referenced, rather than described, in a tone that reads like a VICE column (where Barrodale is Fiction Editor and has written extensively) or an episode of Girls.