Fictional Drugs of Literature, Ranked

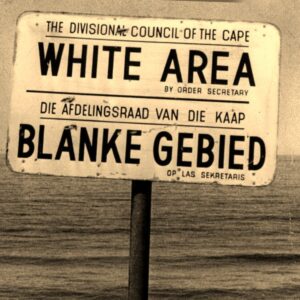

One Pill Makes You Larger

It’s 4/20, and you know what that means: drug-related content on all your favorite websites! Because we’re hip like that. It’s only Thursday, which isn’t the best day for a bender, but certainly close enough to the weekend to celebrate your taxes being done with a little bit of recreational reading—perhaps, if you’re feeling adventurous, about recreational drug use. (NB: it seems like it’s mostly white male writers who make up drugs. Shocker.) On this very official holiday, I’ve put together a selection of 15 fictional drugs as they appear in literature, ranked by the amount I’d like to try them. Spoiler alert: I don’t really want to try most of them at all. But then I’m a square, in case you couldn’t tell, so feel free to add your favorite fictional drugs onto the list below.

1. Soma (Brave New World, Aldous Huxley)

Ah, soma. Huxley’s wonder-drug—”half a gramme for a half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon”—which makes everything feel good and happy and warm, which makes everyone and everything delightful and attractive. More concisely, it has “all the advantages of Christianity and alcohol; none of their defects.” Which, wow.

Okay, so I know soma ultimately makes human life cold, empty, and meaningless, but still—doesn’t it sound good? For daily use.

2. The lotus flowers (The Odyssey, Homer)

Because all is well in the land of the Lotus-eaters:

Any crewmen who ate the lotus, the honey-sweet fruit,

lost all desire to send a message back, much less return,

their only wish to linger there with the Lotus-eaters,

grazing on lotus, all memory of the journey home

dissolved forever.

(trans. Robert Fagles)

When to take it: a summer afternoon by the pool when you honestly cannot be bothered to think of anything, possibly ever again. Augment with a cocktail and some bread and honey and brie, to be festive.

3. Melange (spice) (Dune, Frank Herbert)

The universe of Dune runs on spice, which comes from the sands of Arrakis. Not only does it make humans healthier and live longer, but in some, it can heighten perception to the point of prescience—which is what makes interstellar travel possible. It tastes like cinnamon, “but never twice the same,” as one character puts it. “It’s like life—it presents a different face each time you take it. Some hold that the spice produces a learned-flavor reaction. The body, learning a thing is good for it, interprets the flavor as pleasurable—slightly euphoric. And, like life, never to be truly synthesized.” Of course it is also “a poison—so subtle, so insidious… so irreversible. It won′t even kill you unless you stop taking it.” Indeed, withdrawal is fatal, which is a problem, because it’s extremely addictive. Whatever, though—why would you stop taking a drug that would make you live young forever? Also for daily use, because otherwise you’ll die.

4. Verbaluce™ (“Escape from Spiderhead,” George Saunders)

Now, to be fair, I wouldn’t want to be in the same scenario as the characters in Saunders’s short story—humans as lab rats—but I wouldn’t mind some of their drugs once and a while. After all, that’s why they’re making them, right? Of particular interest to literary types is Verbaluce™:

He added some Verbaluce™ to the drip, and soon I was feeling the same things but saying them better. The garden still looked nice. It was like the bushes were so tight-seeming and the sun made everything stand out? It was like any moment you expected some Victorians to wander in with their cups of tea. It was as if the garden had become a sort of embodiment of the domestic dreams forever intrinsic to human consciousness. It was as if I could suddenly discern, in this contemporary vignette, the ancient corollary through which Plato and some of his contemporaries might have strolled; to wit, I was sensing the eternal in the ephemeral.

For book parties, obviously. Perhaps listicle-writing, also.

5. Nepenthe (The Odyssey, Homer)

Sorry, The Odyssey again! The drug Helen gives to Menelaus’s men translates literally as “not-sorrow”—which sounds ideal to me, except possibly for the fact that this is a not-sorrow brought about by forgetting, which seems like it could have some side-effects:

Into the mixing-bowl from which they drank their wine

she slipped a drug, heart’s-ease, dissolving anger,

magic to make us all forget our pains…

No one who drank it deeply, mulled in wine,

could let a tear roll down his cheeks that day,

not even if his mother should die, his father die,

not even if right before his eyes some enemy brought down

a brother or darling son with a sharp bronze blade.

So cunning the drugs that Zeus’s daughter plied,

potent gifts from Polydamna the wife of Thon,

a woman of Egypt, land where the teeming soil

bears the richest yield of herbs in all the world:

many health itself when mixed in the wine

and many deadly poison.

(trans. Robert Fagles)

When to take it: before funerals, obviously. Also after meetings.

6. The unnamed potion (Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare)

The friar gives Juliet a drug that will make her seem as though she is dead, and um, spoiler: it works a little too well. Hence all the tragedy. But it’s actually a crazy fantastical element in this otherwise straightforward play:

Take thou this vial, being then in bed,

And this distilled liquor drink thou off;

When presently through all thy veins shall run

A cold and drowsy humour, for no pulse

Shall keep his native progress, but surcease:

No warmth, no breath, shall testify thou livest;

The roses in thy lips and cheeks shall fade

To paly ashes, thy eyes’ windows fall,

Like death, when he shuts up the day of life;

Each part, deprived of supple government,

Shall, stiff and stark and cold, appear like death:

And in this borrow’d likeness of shrunk death

Thou shalt continue two and forty hours,

And then awake as from a pleasant sleep.

When to take it: you’ve heard of ghosting, right? This is an even more efficient way to break up with someone who won’t get the hint. They will totally never call you again after you die!

7. Pipe-weed (The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien)

Contrary to popular belief (and suggestion in the films), Tolkien’s pipe-weed is closer to tobacco than it is to marijuana. Be that as it may, it sounds very pleasant and relaxing. Still, it’s down here in the middle of the list because it’s boring. You can smoke it any old time. But unless you have wizard powers, you’ll probably get cancer after.

8. Tripizoid (Hystopia, David Means)

In Hystopia, doctors treat PTSD by forcing the patient to reenact their traumatic experience while under the effects of a drug called Tripizoid (“little greenies, we called them, no bigger than a saccharine tablet”)—which, when successful, allows them to forget the whole experience. Enfolding, it’s caused. “Without the drug Tripizoid the enfolding process doesn’t work and the reenactment of the trauma isn’t properly confused with reality. Tripizoid somehow incites a doubling-back of memory, a mnemonic riptide—the great drawback of water before the tsunami of pure memory arrives, except that it never arrives but is simply conjoined with the withdrawing events.” I hope the need for this never comes up in my life, but even if it does, there’s reason to be a little leery. After all, folds are still there—they’re just hidden.

9. Milk-plus (A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess)

At the Korova Milkbar, which has no liquor license, you instead order milk-plus—that is, “milk plus something else… vellocet or synthemesc or drencrom or one or two other vesches which would give you a nice quiet horrorshow fifteen minutes admiring Bog And All His Holy Angels And Saints in your left shoe with lights bursting all over your mozg. Or you could peet milk with knives in it, as we used to say, and this would sharpen you up and make you ready for a bit of dirty twenty-to one…”

No thanks on the ultra-violence, but I could do with some lights bursting all over my mozg. I suppose I’d have to choose the correct “something else.”

10. Dylar (White Noise, Don DeLillo)

Dylar cures the user’s fear of death. Well not cures, exactly. “The drug specifically interacts with neurotransmitters in the brain that are related to the fear of death,” Babette tells us. “Every emotion or sensation has its own neurotransmitters. Mr. Gray found fear of death and then went to work on finding the chemicals that would induce the brain to make its own inhibitors.” But then there are the side effects: “outright death, brain death, left brain death, partial paralysis, other cruel and bizarre conditions of the body and mind.” Plus, there’s the possibility that the drug doesn’t work at all. For use in Trump’s America.

11. Denner resin (The Name of the Wind, Patrick Rothfuss)

Denner resin comes from trees; it is a very addictive opiate that, as a side effect, leaves your teeth bright white. It makes you feel good, but also drives you mad. For use in small amounts, as a pain reliever, and only under competent supervision.

12. Blanketrol (Gun, With Occasional Music, Jonathan Lethem)

“Blanketrol is very crude stuff,” we are told. “It was the original prototype for Forgettol. They withdrew it when they found out it was completely hollowing out the inner life of the test subjects. The users went on functioning, but just by rote. … Think of it as the opposite of déjà vu—nothing reminds you of anything, not even of itself.” More forgetting—what is it with all these novels? That said, this still sounds less terrifying than:

13. DMZ (Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace)

The “incredibly potent” hallucinogen DMZ, aka Madame Psychosis, chemically resembles “some miscegenation of a lysergic with a muscimoloid, but significantly different from LSD-25 in that its effects are less visual and spatially-cerebral and more like temporally-cerebral and almost ontological, with some sort of manipulated-phenylkylamine-like speediness whereby the ingester perceives his relation to the ordinary flow of time as radically (and euphorically, is where the muscimole-affective resemblance shows its head) altered.” In case that means nothing to you, as it does to me, it’s also described as “the single grimmest thing ever conceived in a tube,” and, more evocatively, “acid that has itself dropped acid.” With sideburned hipsters printed on the tablets. According to Pemulis, it was only made in the early 70s, and “used in certain shady CIA-era military experiments.”

Anyway—it’s possible that this is what causes Hal’s condition at the chronological “end” of the novel—and also possible that it is not. Either way, I wouldn’t risk it, despite the obvious cool factor.

14. Substance D (A Scanner Darkly, Philip K. Dick)

D for Death, of course. Slow Death. Also for “Dumbness and Despair and Desertion.” In Dick’s classic, Bob Arctor lives a double life: as a narcotics agent and also as a junkie, who gets addicted to the psychotropic Substance D. But then the drug causes his brain to literally split in half, each hemisphere functioning independently from the other. Which leads to a certain amount of paranoia. And hey, after the horrifying withdrawal period, it can leave your brain damaged! No thanks, friends.

15. BlyssPluss (Oryx and Crake, Margaret Atwood)

Crake’s plan to improve the world with a pill that will “eliminate the external causes of death” doesn’t exactly go as planned (at least as planned by other people). BlyssPluss:

a) would protect the user against all known sexually transmitted diseases, fatal, inconvenient, or merely unsightly;

b) would provide an unlimited supply of libido and sexual prowess, coupled with a generalized sense of energy and well-being, thus reducing the frustration and blocked testosterone that led to jealous and violence, and eliminating feelings of low self-worth;

c) would prolong youth.

These three capabilities would be the selling points, said Crake; but there would be a fourth, which would not be advertised. The BlyssPluss Pill would also act as a sure-fire one-time-does-it-all birth-control pill, for male and female alike, thus automatically lowering the population level.

There’s also a fifth, very unadvertised capability, of course, which is why this is at the bottom of the list.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.