Everything is Not Fine If It's Not Fine for Everyone

Morgan Babst Sees the Water Rising All Over America

I broke down at school drop-off as soon as I let my daughter out of my arms and turned away again to the outside world. The other parents—all white this morning, always all liberal—were lingering at the doorstep, trying to comfort each other. There would be checks and balances, some hoped, even with Republicans in control of the House and the Senate and Supreme Court nominations to make. The Republicans had loosened the filibuster rule, one mom remembered, meaning that our large minority of Democratic senators might have at least a last resort. One dad even reached as far for solace as to say that corporations run the country anyway, and corporations prefer stability to whatever Trump-concocted chaos might ensue. He then offered me a hug. We were, they said, lucky to be in New Orleans: a self-caring community, a “big blue dot.”

I waited for my friend Catherine, the only other native New Orleanian in the bunch, but she had not yet arrived with her son. As another friend spoke of asking her history professor husband for some silver lining which he could not give, I waited for Catherine, who has a lineage that includes one of the city’s first black officials, elected during that brief period of Reconstruction when this was suddenly possible—and then was not possible anymore. I waited, but she did not come, and having embarrassed myself, I got into my car and cried myself home.

Puddles still shone in the pot-holed avenue from Monday’s street flooding, and I realized, as the dog, car, and I splashed through them, that I was waiting for Catherine because I wanted someone who understood. My husband had already texted to suggest we have dinner out to recuperate. Everyone was trying to find a way for it to be okay. But I know—and I know that Catherine knows—that sometimes it is not.

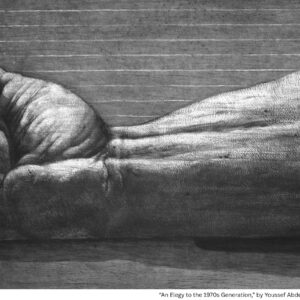

Eleven years ago, New Orleans was abandoned by our government because we are a poor city, and a black one. Eleven years ago, we suffered a cataclysm because the interests of oil and our insignificance to power had left us vulnerable to the sea. The city got herself up, dried herself off, and she continues now, in some ways stronger, in many ways harmed, her motto now not so much Laissez les bons temps rouler, but Take care of yourself, darlin’. (‘Cause no one else will.)

I had tried that philosophy earlier in the morning on my daughter, desperate for a way to break the news that the “bad guy” had won while letting her know that we would survive it. I told her that we would have to be stronger now that we could not rely on the government to protect us, that we would have to care for our neighbors like we had never cared for them before. But as much as I wanted to believe what I was saying, I could not: I know that we as individuals cannot do it all alone.

*

On November 2, 2004, I stood among other American expats outside an Irish pub in Paris, watching the election results come in. A haze of cigarette smoke hung over the sidewalk, and we sipped at our Jameson, and everyone around me got angrier as each state was called. I wandered through the mist, displeased. I had stood in line at the American consulate to send in my absentee ballot (returned to me later marked “address unknown,” though the envelope was pre-printed by the government) and did not want another Bush term. But the year before I had held one of the First Daughters’ hair back in the bathroom at an after-party at Yale, and the next year I planned to go to the Sorbonne. Meanwhile, I was riding around Paris on the back of my salsa-dancing boyfriend’s motorcycle, writing a novel fueled by two-euro wine. I was not panicked, even for my country. Everything was going to be fine.

I returned to the US to get my student visa in order a month before Katrina hit. I made friends with a girl from Lyon, polished my manuscript. On the morning of August 28th, I woke up to the smell of frying bacon and thought, Oh, good. We’re not evacuating. Everything is going to be fine. Then I heard the sound of a hammer: my father was nailing plywood to the windows to save them from the wind. On our way out of town, as small tornadoes formed on the lake just beside the bridge, the girl from Lyon huddled in the backseat, losing command of her English.

I remember it wrong. Instead of George W. Bush peering out of the window of Air Force One as he flew over a flooded New Orleans on his way back from vacation on August 31st, I see him reading a book to school children, as he did while the towers fell. I remember Gov. Katherine Blanco’s refusal to allow aid to enter Louisiana as a caution ribbon wrapped around the state and tied in a big yellow bow. I find in myself a perverse pity for Ray Nagin, sentenced to ten years in jail for corruption; I imagine him huddled in a locked hotel room, in full blown nervous breakdown, as the city he was responsible for filled up like a bowl.

What I do remember clearly: The Jefferson Parish police standing in the middle of Crescent City Connection, shooting over the heads of those trying to cross the river to safety. The crowds waiting in the heat outside of the Convention Center for buses that did not come. The multi-part story in the Times Picayune that told us in advance that the levees were underbuilt, that the storm was inevitable. I remember who we neglected, who we feared, what we called them. But most of all, I remember that we did nothing, because everything was going to be fine.

*

I am sitting on my Garden District lawn as I write this, watching the traffic plod placidly by. The dog tracks a squirrel in the branches of the water oak. It would be comfortable to believe that this is fine.

Though I am a woman and feel assaulted every time I hear the voice that bragged of grabbing women by the pussy, I am white, cis, straight, wealthy, and married. I, personally, should be fine—more fine that the just-out trans daughter of a dear friend, more fine than my black friends who would like to stop being beaten and killed by the police, more fine than the Muslim woman who helped me to care for my child in the first two years of her life, who has three children to raise in a world who have just announced their hate of them. But the truth is, under this new regime, none of us can be assured of being fine, not even the white middle-class men and women who voted for Trump under the misguided belief that their success and safety are predicated on the exclusion and expulsion of others.

We will be fine, we say standing around in a white huddle in front of the doors of our private schools, forgetting that that any real we includes those who will not be fine, cannot be, under a government that overtly expresses its indifference—and hostility—to their well-being. My house is on the natural levee, but this whole place is going under.

Morgan Babst

Morgan Babst is a New Orleans native. Her debut novel, The Floating World, will be published next October by Algonquin Books. Her essays and fiction have appeared in such publications as Guernica, The Harvard Review, and The New Orleans Review.