Elliptical and Black: Roxane Gay in Conversation with Rion Amilcar Scott

On Representation, Superheroes, and the Failure of the Market

It’s common to hear writers of color speak of reading a particular book by a writer who shares their background or encountering a writer who shares cultural similarities and suddenly feeling permission to write the things they need to write. Previous to this revelation said writer has looked and looked, but found few mirrors, few reflections of themselves in the popular culture. Or worse yet, any reflections they see are distorted, lopsided and malformed versions of themselves. Once upon a time Roxane Gay spoke via Skype to my class of Bowie State University creative writing students. The class that semester happened to be made up entirely of black women. I could see it in their faces as we discussed Roxane’s work previous to the Skype call and in their questions and comments as they spoke to Roxane and after as we continued our discussions—I realized my students were gazing into a mirror; in that reflection they found the permission to write the stories they needed to write. In this conversation, Roxane and I discuss our work and the problems of proper cultural representation.

–Rion Amilcar Scott

Rion Amilcar Scott: As a comics lover I became excited (probably unreasonably so) when I heard that you, along with poet Yona Harvey, had been drafted to be among the first black women to write for Marvel Comics with the upcoming World of Wakanda series. On one hand it seems like an almost farflung and random choice given what you’ve published previously, but from another perspective it makes all the sense in the world given your focus on writing black women, queer women, etc. into a greater and more complex visibility. How do you see this project fitting into the larger Roxane project?

Roxane Gay: When Ta-Nehisi Coates emailed me and said, “I have a crazy idea,” I had no idea what would happen next. I never dreamed I would write a comic book but here we are. It is a thrilling opportunity and I took it on because black women and black queer women are so underrepresented in most forms of popular culture but especially comics. In fiction and nonfiction, I love to write women’s stories, so while this is an unexpected opportunity, it is well in line with the work I do.

What is the larger Rion project? And how does your short story collection, Insurrections, fit into that project?

RAS: When I stepped on the campus of Howard University as a student so many years ago I was struck by how many different versions of blackness I’d encounter on a given day. Coates writes about this a bit in his second book. In my fiction I’m attempting to write about blackness in the varied and multitudinous ways that I’ve experienced it. We tend to see a limited range of black representations in pop culture, which I think in turn limits everyone’s imagination. It’s tempting to say that things are changing, but I don’t think progress is really a straight line—who would have thought voting rights would be an issue in the 21st century?—so it’s important to keep the pressure on. I suppose Insurrections is a first salvo—an introduction to the world of Cross River, Maryland, a town founded by slaves after a slave revolt. I plan to go to a lot of different places with this fictional world.

I know you’ve been bombarded with people telling you about things they think you should read while working on World of Wakanda, but Roxane, if you haven’t already, you really must read some of the Milestone Comics line from the 1990s. Some black creators got together to create a diverse comics universe and, at least early on, it was excellent. My favorites were Icon and Blood Syndicate, particularly for the range of humanity the writers gave these characters of color. I was so used to being insulted whenever a black character entered a comics panel. Milestone felt real, black and urgent. A very short lived experiment but it really did leave a mark on me. What sort of things are you reading—comics or otherwise—to inspire your World of Wakanda writing?

RG: I will definitely check out Icon and Blood Syndicate. I found the Milestone Comics archive online! In terms of reading—I read some Saga, which I will continue to read because I am enjoying it. I also read some Ultimates, The Wonder Woman Rebirth and I have Monstress and Sex Criminals queued up. Certainly, I read Ta-Nehisi’s Black Panther. I also read two books on how to write comics that were interesting but not super helpful because they were so basic in what they had to say. In truth, I don’t want to read too much work by way of influence. Marvel knew who I was when they hired me and I have to trust that they hired me for a reason—because I know how to tell a story. I’m going to just do my best to honor the tradition and the world I am writing into while telling the story of the Dora Milaje, as I want.

You bring up an interesting question when you talk about your work. Why do we see such a limited range of blackness in popular culture? Where are some of the places you want to go in Cross River and the world you’ve created there? And how do you build a fictional place like Cross River—what kind of work do we see on the page, and what kind of work are you doing off the page?

RAS: Whenever we talk about the limited range of black portrayals we blame the usual suspect: not enough people with an understanding (or real interest in gaining such an understanding) of black folks in charge. One thing I think we often overlook is how soothing these portrayals can be for white viewers and readers. You touch on this in your essay from Bad Feminist about going to see that sci-fi-fantasy adventure movie, The Help. Each time I’ve read it the thing that’s stood out most is the applause and moved tears of the white moviegoers. It was obvious to me and to you and a lot of black moviegoers that what was up on that screen was mostly offensive caricature. It did a lot of work, however, to maintain the image of white saviors vanquishing evil white folks to empower the weak and childlike darkies. Even the most toxic parts of the status quo are soothing to someone. And sometimes even when the toxic parts are recognized to be toxic, they are still better to some than change, which can be scary. Something as simple as presenting a more varied range of humanity is confrontational. And well, most people don’t like confrontation. I can dig it. I don’t like it either for the most part, but it’s necessary.

We’re told often that the solution is the market, that great capitalist equalizer. Buy more black books and we’ll see more black authors, more varied black characters. We know that black women read and buy the most books. If the market was going to save us by now it would have.

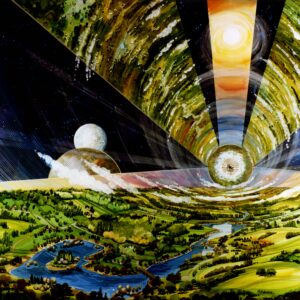

With Cross River I want to create something weird and elliptical and black. I think there is a promise of future bizarreness in Insurrections and I definitely want to fulfill that—the Black Bizarre. I want to follow it in whatever direction it is going as well as I hope to allow it to grow and change with me. Off the page there is a lot of daydreaming, make-believing that the place is in motion even when I’m not sitting in front of a screen. It’s very much the way I used to approach playing with my action figures, my stuffed animals. On the page it’s one character at a time interacting with his or her environment. Whatever happens with him or her is what builds Cross River. Or sometimes it’s what happens with me, a misheard rap lyric might become an imagined Caribbean nation. Memories of a childhood game of aggression become a revered professional sport. It’s great fun.

You know, we often talk about representation and such like it’s an “eat your vegetables” kind of thing. I know I’ve been guilty of that. We all read fiction to engage in an experience and to feel a range of emotions. In short, I read because it’s a fun thing to do. For instance, looking at my shelf, reading Daniel José Older’s books are a blast and it feels like the diversity of his work is part and parcel of that.

Your upcoming short story collection, Difficult Women, has one of those titles that feels like it makes a statement (same with your upcoming memoir, Hunger—also the same with all your other books, actually) what is it you hope readers come away with from your upcoming works—not in the “eat your damn vegetables” sense that we often talk about this, but in the real human engagement sense?

RG: I hope readers walk away from reading Difficult Women with the sense that the world is a dark place, but still, somehow, we find a way to want, to need, to love. The same could be said for most everything I write.

Rion Amilcar Scott’s Insurrections is available now from University of Kentucky Press.