Duke Ellington Really Just Wanted to Be a Writer

On the Literary Sensibilities of a Great American Musician

One of the main assumptions in thinking about African American creative expression is that music—more than literature, dance, theater, or the visual arts—has been the paradigmatic mode of black artistic production and the standard and pinnacle not just of black culture but of American culture as a whole. The most eloquent version of this common claim may be the opening of James Baldwin’s 1951 essay “Many Thousands Gone”: “It is only in his music, which Americans are able to admire because a protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it, that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story. It is a story which otherwise has yet to be told and which no American is prepared to hear.” Eleven years later, Amiri Baraka put it even more forcefully, excoriating the “embarrassing and inverted paternalism” of African American writers such as Phyllis Wheatley and Charles Chesnutt, and claiming flatly that “there has never been an equivalent to Duke Ellington or Louis Armstrong in Negro writing.” Such presuppositions and hierarchical valuations have been part of the source of a compulsion among generations of African American writers to conceptualize vernacular poetics and to strive toward a tradition of blues or jazz literature, toward a notion of black writing that implicitly or explicitly aspires to the condition of music.

I want to start by juxtaposing these stark claims with an early essay by one of the musicians they so often cite as emblematic. Duke Ellington’s first article, “The Duke Steps Out,” was published in spring 1931 in a British music journal called Rhythm. “The music of my race is something more than the ‘American idiom,’” Ellington contends. “It is the result of our transplantation to American soil, and was our reaction in the plantation days to the tyranny we endured. What we could not say openly we expressed in music, and what we know as ‘jazz’ is something more than just dance music.” This would seem to be in keeping with an assumption that black music articulates a sense of the world that could not be expressed otherwise—that it “speaks” what cannot be said openly. Yet Ellington, in moving on to describe the African American population of New York City, offers a somewhat different reading of the music that was being produced in that context, specifically in relation to the literature of the Harlem Renaissance that had exploded into prominence in the previous decade. He writes:

In Harlem we have what is practically our own city; we have our own newspapers and social services, and although not segregated, we have almost achieved our own civilization. The history of my people is one of great achievements over fearful odds; it is a history of a people hindered, handicapped and often sorely oppressed, and what is being done by Countee Cullen and others in literature is overdue in our music.

Here, what we so often suppose to be the dynamics of influence between black music and literature is inverted—in Duke’s view, the achievements of the literary Renaissance are a model for his own aspirations in music. He continues: “I am therefore now engaged on a rhapsody unhampered by any musical form in which I intend to portray the experiences of the colored races in America in the syncopated idiom.” In a remarkably early reference to his lifelong ambition to compose a “tone parallel” to African American history—an ambition that would find partial realization in later works like Black, Brown and Beige and My People—Ellington makes no apologies for his desire to “attribut[e] aims other than terpsichore to our music.” Indeed, he adds, “I am putting all I have learned into it in the hope that I shall have achieved something really worthwhile in the literature of music, and that an authentic record of my race written by a member of it shall be placed on record.” My aim here is not of course to undermine the importance of black music or to crudely promote the literary at its expense but to begin to challenge some of our assumptions about the relations among aesthetic media in black culture. Looking at the literary Duke, at Ellington as writer and reader, I want to reconsider just what that provocative phrase—“the literature of music”—might mean.

The Uses of the Literary

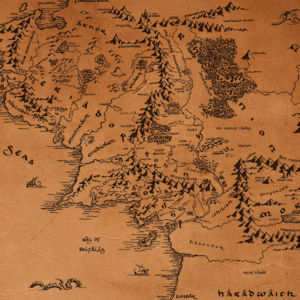

It is well known that Duke Ellington based a number of his compositions on literary sources. One thinks of the 1943 New World A-Comin’, based on the Roi Ottley study of the same name; Ellington’s aborted plans to adapt South African novelist Peter Abrahams’s Mine Boy (1946); Suite Thursday (1960), the Ellington-Billy Strayhorn suite based on John Steinbeck’s 1954 novel Sweet Thursday; and the so-called Shakespearean Suite, also known as Such Sweet Thunder (1957). There are many more compositions that involve narrative written by Ellington and/or Strayhorn (either programmatic, recitative, or lyric) in one way or another, including A Drum Is a Woman (1956); The Golden Broom and the Green Apple (1963); The River (1970); and of course the Sacred Concerts in the 1960s. Barry Ulanov has commented that “Duke has always been a teller of tales, three-minute or thirty. . . He has never failed to take compass points, wherever he has been, in a new city, a new country, a redecorated nightclub; to make his own observations and to translate these, like his reflections about the place of the Negro in a white society, into fanciful narratives.”

What is remarkable, in this wealth of work, is the degree to which Ellington was consistently concerned with “telling tales” in language, not only in sounds—or, more precisely, in both: spinning stories in ways that combined words and music. Almost all the extended works were conceived with this kind of literary component, even though Ellington’s attempts at mixing narrative with music were for the most part dismissed by critics. The bizarre and misogynist vocal narration performed by Ellington himself on A Drum Is a Woman was mocked as “monotonous” and “pretentious” and as “purple prose,” with even favorably disposed reviewers like Barry Ulanov complaining that “there is no point in analyzing the script. Such banality, such inanity, such a hodgepodge does not stand up either to close reading or close listening.” And yet Duke’s desire to write remained constant. Asked to speak to a black church in Los Angeles in 1941 on the subject of Langston Hughes’s poem “I, Too,” Ellington commented, “Music is my business, my profession, my life . . . but, even though it means so much to me, I often feel that I’d like to say something, have my say, on some of the burning issues confronting us, in another language . . . in words of mouth.”

Ellington also wrote poetry. He showed some of his writing to Richard Boyer, who in 1943 was preparing a now-legendary portrait of Ellington for the New Yorker: “New acquaintances are always surprised when they learn that Duke has written poetry in which he advances the thesis that the rhythm of jazz has been beaten into the Negro race by three centuries of oppression. The four beats to a bar in jazz are also found, he maintains in verse, in the Negro pulse. Duke doesn’t like to show people his poetry. ‘You can say anything you want on the trombone, but you gotta be careful with words,’ he explains.” Nevertheless, some of Ellington’s poems are collected in Music Is My Mistress and there are even a few recordings of Ellington reciting poetry in concert. Some of these performances are whimsical, couched as a humorous interlude to the music, as when Duke recites a short, colloquial quatrain at a Columbia University date in 1964 and prefaces it with the nervous disclaimer that “I wanted to tell it to Billy Strayhorn the other day in Bermuda, and he went to sleep. . . So I still haven’t done it”:

Into each life some jazz must fall,

With after-beat gone kickin’,

With jive alive, a ball for all,

Let not the beat be chicken!

Another example is a poem entitled “Moon Maiden,” which Ellington recorded in a session for Fantasy Records on July 14, 1969. He plays celeste on the 36-bar tune, and recites (in an overdub, since he is snapping his fingers, as well) two brief stanzas before taking a solo:

Moon Maiden, way out there in the blue Moon Maiden, got to get with you

I’ve made my approach and then revolved But my big problem is still unsolved Moon Maiden, listen here, my dear

Your vibrations are coming in loud and clear

Cause I’m just a fly-by-night guy,

But for you I might be quite the right “do right” guy Moon Maiden, Moon Maiden, Lady de Luna

In the liner notes, Stanley Dance comments that this “unique” selection originated when Ellington’s imagination “had been stimulated by the thought of men walking around on the moon, and he had not uncharacteristically visualized their encountering some chicks up there.” These lyrics comprise only one among a number of works that reflect Ellington’s fascination with the space race, like “The Ballet of the Flying Saucers” in A Drum Is a Woman (1956), “Blues in Orbit” (1958), “Launching Pad” (1959), and unperformed lyrics like the undated “Spaceman,” with its more lascivious reveries: “I want a spaceman from twilight ’til dawn/ When the chicks say there he is he’s really gone /. . . Give me a spaceman on a moonlit nit [sic] / Who can fly further than he’ll admit/ One whose cockpit is out of this world/ Been around so much he’s even had his stick twirled.”

Stanley Dance writes that the “felicitous internal rhymes” of “Moon Maiden” come off Duke’s tongue “as though phrased by plunger-muted brass,” but surely it is important that Ellington conceives the piece as a vocal recitation, not an instrumental number or a sung lyric. Indeed, he had “recorded the number twice as an instrumental, and with at least a couple of singers, but each time he remained dissatisfied.” At one concert around this time, Ellington introduced the piece by saying that “Moon Maiden represents my public debut as a vocalist, but I don’t really sing. I’m a pencil cat. My other number will be, I Want to See the Dark Side of Your Moon, Baby. . . Extravagance going to the moon? Extravagances have always been accepted as poetic license.” In other words, Ellington was deliberately seeking a kind of rhetorical—and apparently libidinal—excess that he considered to necessitate a poetic form, one in which “extravagances” would be accepted.

I want to focus briefly on what we might term this literary imperative in the Ellington oeuvre, which is not by any means limited to Duke’s efforts at programmatic narrative or poetry. In his brilliant autobiographical suite, Music Is My Mistress, Ellington writes of a more general narrative or “storytelling” impulse behind the very process of creating music, arguing for the necessity in music of “painting a picture, or having a story to go with what you were going to play.” He goes on to claim (like a number of other jazz musicians) that soloists could “send messages in what they play,” articulating comprehensible statements to one another on their instruments while on the bandstand. “The audience didn’t know anything about it, but the cats in the band did,” he adds. But he also noted that “stories” were sometimes necessary to the composition and arrangement process, and often verbalized in language—with Duke talking the band through a new or unfamiliar tune with the guidance of a tall tale or two. The band seldom turned to collaborative arrangements (with all the musicians contributing to the construction of a song), but the anecdotes of that process are legendary, and fascinating for just this reason. Ellington describes it this way:

Still other times I might just sit down at the piano and start composing a little melody, telling a story about it at the same time to give the mood of the piece. I’ll play eight bars, talk a bit, then play another eight and soon the melody is finished. Then the boys go to work on it, improvising, adding a phrase here and there. We don’t write like this very often and when we do it’s usually three o’clock in the morning after we’ve finished a date.

But this is a little off the point. What I am trying to get across is that music for me is a language. It expresses more than just sound.

A more vivid description of the same process is provided in Richard Boyer’s “The Hot Bach,” which is worth quoting at some length:

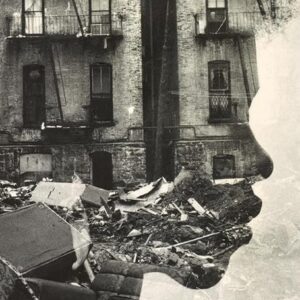

The band rarely works out an entire arrangement collectively, but when it does, the phenomenon is something that makes other musicians marvel. This collective arranging may take place anywhere—in a dance hall in Gary, Indiana, in an empty theatre in Mobile, or in a Broadway night club. It will usually be after a performance, at about three in the morning. Duke, sitting at his piano and facing his band, will play a new melody, perhaps, or possibly just an idea consisting of only eight bars. After playing the eight bars, he may say, “Now this is sad. It’s about one guy sitting alone in his room in Harlem. He’s waiting for his chick, but she doesn’t show. He’s got everything fixed for her.” Duke sounds intent and absorbed. His tired band begins to sympathize with the waiting man in Harlem. “Two glasses of whiskey are on his little dresser before his bed,” Duke says, and again plays the two bars, which will be full of weird and mournful chords. Then he goes on to eight new bars. “He has one of those blue lights turned on in the gloom of his room,” Duke says softly, “and he has a little pot of incense so it will smell nice for the chick.” Again he plays the mournful chords, developing his melody. “But she doesn’t show,” he says, “she doesn’t show. The guy just sits there, maybe an hour, hunched over on his bed, all alone.” The melody is finished and it is time to work out an arrangement for it. Lawrence Brown rises with his trombone and gives out a compact, warm phrase. Duke shakes his head. “Lawrence, I want something like the treatment you gave in ‘Awful Sad,’” he says. Brown amends his suggestion and in turn is amended by Tricky Sam Nanton, also a trombone who puts a smear and a wa-wa lament on the phrase suggested by Brown. . . Now Juan Tizol grabs a piece of paper and a pencil and begins to write down the orchestration, while the band is still playing it. Whenever the band stops for a breather, Duke experiments with rich new chords, perhaps adopts them, perhaps rejects, perhaps works out a piano solo that fits, clear and rippling, into little slots of silence, while the brass and reeds talk back and forth. By the time Tizol has finished getting the orchestration down on paper, it is already out of date. The men begin to play again, and then someone may shout “How about that train?” and there is a rush for a train that will carry the band to another engagement.

It is not at all unusual for collaborative musicians and dancers to give each other epigrammatic or narrative clues during the compositional or choreographic process. Here, though, the arrangement seems to start off from the narrative, with Duke’s self-accompanied performance—the tired band members are drawn into the creative process by the scene Duke sketches as he speaks. Here, in the middle of the night, at the core of what drives the band’s extraordinarily creative cohesiveness, is an intimate call-and-response between words and music, narrative instigation and the subsequent musical contextualization of a melody. It is almost a commonplace by now to describe Ellington’s music with superlative literary analogies, as a “drama of orchestration” or a “theatre of perfect timing.” Some critics have gone so far as to write about the “Shakespearean universality” of Ellington’s music, contending that it is akin to the Bard’s plays “in its reach, wisdom, and generosity, and we return to it because its mysteries are inexhaustible.” But part of what I am suggesting is that the literary is less an analogy for Ellington’s music, than an inherent element in his conception of music itself, and a key formal bridge or instigating spur in his compositional process.

__________________________________

From Epistrophies by Brent Hayes Edwards, courtesy Harvard University Press. Copyright Brent Hayes Edwards, 2017.

Brent Hayes Edwards

Brent Hayes Edwards is Professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University. He is also author of Practice of Diaspora.