Daniel Riley on Skyjackings, Joan Didion, and 1970s California

In Conversation with the GQ Editor and Fly Me Author

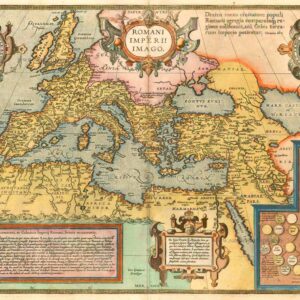

Fly Me, the sensual and sun-bleached debut novel from GQ Senior Editor and Manhattan Beach transplant Daniel Riley, tells the story of Suzy Whitman—an amateur racecar driver and Vassar graduate with a thirst for adventure who follows her older sister Grace to the beaches of Southern California and a job stewardessing with Grand Pacific Airlines. The year is 1972. Mick Jagger and Rolling Stones are at the height of their peacocking powers, Nixon’s White House is under investigation, Jim Jones is spreading his sinister gospel, and an epidemic of skyjacking has taken hold in the clouds above America. For Suzy, what begins as an escape to the chilled-out surf and party scene of Sela del Mar, Riley’s lushly rendered fictitious beach town, becomes a dark descent into the world of drug-trafficking.

I sat down with Riley in the decidedly non-beachy setting of Swift Hibernian Lounge in the Bowery last week, where we chatted about Jim Jones, Joan Didion, the lure of beach living, and our enduring fascination with the dangerous and debauched 1970s.

Dan Sheehan: Vibrant descriptions of your imagined Southern California beach town Sela Del Mar, and of the west coast period atmosphere in general, jump out of this novel right from the beginning. Describing a book’s setting as a character has become somewhat of a cliché, but in this case it does seem particularly apt. Beyond its pleasures as a lushly drawn backdrop, the power that this region holds over these characters feels like an active seduction.

Daniel Riley: Well, what you’ve just described was actually the original intention. At the beginning, I didn’t have a plot in mind; I didn’t have any these characters. The question for me was, how do you write a book that is about the thing that Southern California beach towns do to people psychologically? Which is a very strange and challenging place to begin a story that needs to have people and action at the center of it. How do you show the way in which this place can grab you and slow you down? The four main characters represent the spectrum of people you’ll find in this kind of place. You’ve got the total insider who has never been anywhere else, and then you’ve got these three outsiders whose range of experiences run from falling for it immediately, to being somewhat skeptical but open to it, to feeling wholly skeptical and outside of it.

It’s strange, there are all these people who live in the beach towns of Southern California and yet there aren’t a ton of serious books that attempt to get beyond the sparkle of the sun on the water kind of focus to ask what happens to people’s brains when they are raised here, or leave and come back, or are raised somewhere entirely different and end up here. What I wanted for the novel is to try to help the reader understand how this region could drive somebody to a place that they’re not supposed to go. How it could lull you into an easy feeling of carelessness or give you that little boost of nerve, making you feel like you’re capable of more than you are.

I think that I have, at different points, felt like all four of those characters in relation to my home town. I left Manhattan Beach nine years ago but I go back a lot; I probably go back eight or nine times a year, and when I do I pay extra careful attention to what happens to my brain when I get there. I start off as this crazy, driven person who, in the first twenty-four hours, kind of hates it—everybody pisses me off and it feels like no one cares about anything or knows what’s going on in the news. Then, after twenty-four hours, I feel it all melt away and all I want to do is go for a walk with my mom or spend six hours on the beach. So what I was trying to do was to write a book that smuggles all that stuff into a story that is also about these characters and the crime and action that they become involved in.

DS: I’m fascinated by the dueling obligations at work in Southern California: the requirement to be simultaneously in a state of reclined bliss, and determinedly striving toward success in a romantic and oftentimes almost impossible-to-succeed-in field. Your epigraph, from Joan Didion’s “Notes From a Native Daughter,” describes it as “a place where a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension.”

DR: Right, because for most people not only are you supposed to succeed when you arrive, but it often carries the extra weight of being the place you escaped to. That sense of, well I didn’t make it or could find my footing somewhere else, but here is where it’s going to work, where it has to work. And that again is what’s interesting about having these three different outsiders in Mike, Grace, and Suzy; each of them has a different idea of what that is about. It goes back to what Didion says: “Things better work here, because here is where we run out of continent.” It’s that idea of being pushed to the edge.

DS: One of the great pleasures of this book is the subtle nods you give to now-infamous events of the era. We’ve seen a surge in interest in the politics and culture of the 70s of late—from HBO’s Vinyl to books by Jeffrey Toobin and Jeff Guinn on Patty Heart and Jim Jones, to Joan Didion’s recently publicized 1970s notebooks [South and West]. What is it about the decade in American history that has become such a source of fascination to contemporary audiences?

DR: I think that part of it is a sort of natural pop cultural evolution from where we just were. We’ve been presented with a lot of stories of the 60s in recent years, and now we’re putting that behind us and moving on to the next thing. But the reasoning is similar: the period is just distant enough that half of your audience didn’t experience it, and half is nostalgic for it.

It’s also the fact that enough is the same, which makes the little details super fascinating. I was thinking a lot about airplanes and how little has actually changed in their technology in the intervening years. The 737 is the same design, for instance, so you can take something like that, and it’s not like you’re dealing with a horse and buggy. It’s the same airplane, but you’ve added a knife and a gun. So it becomes this uncanny thing where you’re presented with a situation that’s deeply familiar, but the pilots are WWII heroes, the flight attendants have to wear short dresses, and you’re allowed to carry a knife in your pocket. It’s not so far away and so different as to feel out of touch or quaint.

And even when we think about the infamous figures of the era, people like Patty Hearst or Jim Jones—there are still elements of them around. It’s not like after Jim Jones we stopped hearing from cult leaders, you know? All of the things he spoke about, all of the draws, are in the news every day. The way that he would talk about power and politics and religion was incredibly seductive, and you see that in the way that certain political figures cultivate this demagogic draw to them. We think that we’re in a different era and maybe even five years ago, when it seemed like we had moved to a new level of progress, some of this stuff might have felt more jarring. But now we’re right back in the same mud that was very familiar to those who lived through the period in the book.

DS: It was interesting to me that many of the more intimate moments Grace and Suzy share, the moments in which they get to interact with each other in a deeper way, occur on the beach—a place that they have chosen to embrace and that Mike has actively resisted.

DR: Absolutely. With the exception of their trip home, almost all of their time together is spent on the beach or on the strand. I think that there are two different types of people in a beach town: those who do everything they can to get down to the beach, and those who live with their backs to it, who look inland, who look toward downtown LA or Hollywood. The difference between Mike’s approach, and that of Suzy and Grace, is representative of the two different archetypes of people who move to that region. I think of my mom and how every day she goes for a walk on the beach for two hours, and how she sees everybody she knows because they’re all out there walking too. It’s a very old idea that you don’t see very often in America in 2017—people walking down the equivalent of Main Street. I know the people I’m going to meet when I go home and go for a walk on that beach, so of course that’s the place where these characters will do their bonding.

DS: One of the things I love about Mike as a character is that he seems to represent the darker side of that group of iconic 70s writers who we hold in such high esteem today; the frustrated, self-important, ultimately quite callous aspects of that movement of novelists and New Journalism practitioners.

DR: It’s funny, the writer friends of mine who have read this book love talking about Mike because he is one of the most familiar personalities to people who live in New York in that world—they’ve all met a version of this guy. This person who needs to lie to themselves about their writing career, and the anger that builds in them because of that. You see in Mike the closing off of possibilities, the way in which he’s driven himself to the point where there’s only one way out, and in his case that way out is this grand betrayal. In the beginning, on the Forth of July, he is genuinely making an effort. He’s sort of a fish out of water but is charmingly trying all the same. And then he becomes more introverted, he starts to spend more time in the house, and eventually he succumbs to his worst impulses. And I know journalists who have gone to that place.

DS: You don’t get an overt sense at the beginning that these characters are destined to blow up their lives, but they slowly but surely back themselves into their respective corners, and are then forced to adapt to the loss of control in more and more extreme ways. It’s a captivating descent.

DR: Well the book really ignited for me when I was able to establish what I wanted the last scene to be, because then everything could be bending toward that, every piece after part one could be a steady march toward that ending. Little events could occur to lead these characters to a place where their options are slowly eliminated by a variety of choices. I don’t think you can accidently get to that point in a book like this; in order to turn people over this considerably, you have to set things in motion early.

DS: In a way, Suzy’s trajectory reminded me a little of Don Draper’s in Mad Men, in that Suzy, like Draper, begins her story feeling that, by very small margin, she’s missed out on a completely different road. In her case it’s Yale becoming co-ed just a little too late for her.

DR: Right; and it takes the brain of a 22-year-old to think that that would have made the difference, that it would have changed everything. But it stems from that very specific feeling she has, that starts when she’s a little girl, of impatience. She’s not particularly interested in marching or fighting for equal rights; she just wants to skip the line. She doesn’t want to live as a liberated woman, she wants to live with the freedom of a man. She’s sick of being in positions where she’s acted upon by other forces. And it’s not that she’s in over her head, it’s more that these forces are a nuisance to her. At least for the first half of the book, she’s often blaming other people; and then there’s a switch where she decides to do this extreme thing, to take matters into her own hands in order to help her dad. She thinks she’s in control at that point, but of course she’s only plunging herself deeper and leaving herself vulnerable to even greater forces raining down upon her later.

It’s interesting that you mention Mad Men because I was also thinking about The Sopranos, about Tony sitting on Dr. Melfi’s couch in the pilot talking about how he’s feels like he’s missed out on the best days. And that really must be one of the most common feelings in the world. But by having Suzy be this very specific age in California in 1972, it gives you full access to a fascinating place and time. Obviously the skyjacking stuff is at its hottest in 1972—Nixon is pressured to introduce metal detectors in airports on January 4th, 1973 which changes everything and you don’t see anything like that skyjacking craze ever again—but I was also interested in the idea of being born as a woman in America in 1950. It’s a very, very specific year to come into the world in terms of coming of age in the moments just before things turn over. Things like the Marriage Rule for stewardesses at all the airlines. There’s the Supreme Court case in 1976 which, very sanely, rules that if a man can’t be fired for getting married then a woman can’t be either. But up to that point you could find yourself in a situation where you’ve been asked to quit because you got married in, say, 1971, and then five years later married women can work these great 20 year careers but you’ve missed out on all that, and you’re left just sitting there saying “what the fuck?” In Grace’s case, for instance, it’s the job she’s most cut out for on earth and that’s why she’s bearing the secret of her marriage and panicking a little bit because of it.

DS: Who, to your mind, is the quintessential California writer?

DR: Well the Godmother of this book, without question, is Joan Didion. She was the one who turned me on to a whole other way of thinking about home. I had very smart parents who knew a lot of things and read a lot of newspapers but not a ton of fiction or contemporary writers, so I didn’t have much access to that growing up. I didn’t really know who Joan Didion was until college, and even then I was introduced to her not though her journalism but through some of her fiction that I was assigned in class. So it wasn’t even until I started working in magazines that I found those books that a lot of writers I know who love Didion talk about reading at 15 or 16. Here is the person who I consider to be the most important writer I’ve ever read, and I’m not exposed to her until I’m 22 or 23, when she totally blew my mind.

She had written about the thing I was feeling most strongly about at that point which was that idea of inside/outside. I’m from here, I left here, I’ve come back here. When she’s writing about Southern California, throughout the 70s and 80s, she has already left Sacramento, spent her twenties in New York, and come back. So she is able to keep that duality in her writing, asking how would my family feel about this, and how do I feel about it now as a quasi-outsider? That duality has been the guiding force for this book.

This interview has been edited for length

Dan Sheehan

Dan Sheehan is the author of the novel Restless Souls (Ig Publishing) and Editor-in-Chief of Book Marks.