Christos Ikonomou, Accidental Prophet of a Country in Crisis

The Author of Something Will Happen, You'll See in conversation at Green Apple Books

More than any other book I have read in Greek in recent years, Christos Ikonomou’s Something Will Happen, You’ll See speaks to the toll the economic crisis has taken not on a societal level, not on a personal level, but on an interpersonal level. In Ikonomou’s stories, couples, siblings, parents and children, best friends, co-workers, neighbors, even groups of strangers brought together by circumstances, try to carry those relationships forward through a treacherous no-man’s-land of heavy silences and misplaced communication. One of the most poignant stories in the book, for me, is one in which a man whose best friend, a construction worker, has just been killed by an accident on the job; the friend tries to stage a one-man protest, struggles for a long time to think of something to write on his placard, and in the end goes with an empty piece of cardboard held high, unable to find the words. Ikonomou, however, does find the words: his prose is as gorgeous and spare and yet lyrical as any as I have read. It is a book deeply rooted in the contemporary situation in Greece, and even in particular working-class neighborhoods of Athens, but it is also a book that speaks to the heavy price of privation in the lives of the precariat everywhere. At the end of April, Ikonomou sat down with fellow writer Anne Germanacos, at Green Apple Books, to discuss the book, and much more.

–Karen Emmerich, translator

Anne Germanacos: Alright, I thought we’d start with a little reading, and Christos will read a bit from a story which I’ve chosen, called “The Things They Carried,” and then I’ll read, in English, a little bit more than he’s going to read. How many people speak Greek? Just one, two? Okay, but I just wanted you to get a sense of how it sounds in Greek.

Christos Ikonomou: Don’t worry, I’ll keep it short. Just one paragraph. [Reads in Greek]

Germanacos:

They carried their Social Security booklets and identity cards. They carried packs of tissues and keys and coins and a few bills—some in wallets, some shoved into their pockets. Each carried a bottle of water, pills and capsules for his various ailments.

Number five, who’d had rheumatism for years, carried a large brown envelope of x-rays.

Almost all of them carried lighters or matches and extra cigarettes to help them stay awake. Two or three carried bus passes, or tickets for the trolley or metro. Number four, who was 68 years old but had thick grey hair and a thin grey mustache, carried stones in his kidneys and a small black comb in his coat pocket. Number three carried a pair of prescription glasses that he never wore in public because he was embarrassed. Four of the five carried cell phones. Number two, who had brought his folding stool from home, carried in his wallet a photograph of his son who had died the previous month in a car accident in Halkidona. Number one, who was almost blind in his right eye, carried a booklet enumerating the miracles and visions of Saint Efraim the Martyr. He read two or three pages a day, with difficulty, to gather strength or hope or to distract himself from his troubles.

They all carried years of hard work on their backs. They carried deprivations and dreams that hadn’t come true. They carried the weight of the time they had spent with their wives and children. They carried compromises they had accepted, vows they had broken. They carried betrayals they had committed and others that had been committed against them. Deep inside each carried fear and stress and worry about illness and time, which came each day like a conscientious gardener to trim a bit off their lives.

They were poor people, with debt to the banks and unpaid bills.

One of them owed money to a loan shark.

Two or three of them carried lottery tickets, scratch-offs and quick picks.

All of them carried secrets, hidden sins and things they rarely—or never—showed to anyone else.

Number one, who had glaucoma, carried a bracelet made from elephant hair that a woman had given him many years ago at the airport as she was leaving for South Africa.

Number two carried the dog tag his son wore around his neck while a conscript in the army.

Number three had carried a Kershaw knife ever since the night he’d seen two addicts beating an old man for his money down under the pedestrian bridge.

Number four carried a keychain with the keys to his family house on Aegina which he’d been forced to sell for practically nothing.

The one who’d arrived last, number five, carried the coin he’d found in the New Year’s pie five or six years ago. It was the only time in his life he’d gotten the coin in his slice and for a while he carried it around for good luck. At some point the pocket of his winter coat got a hole and the coin fell into the lining and he never went to the trouble of fishing it out. By now he’d forgotten it altogether.

***

They carried lots of old songs, images and memories from their childhood. They carried a nostalgia for the things of the past, a nostalgia that became more and more bitter with the passing of time, and instead of filling them with joy now only made them feel older and less capable.

They carried the smells of their homes. The stale smoke from the coffee houses they frequented. The dirty air of Nikaia. The scent of bitter orange trees blooming around Easter. Sometimes they felt as if they carried the whole city inside them, avenues and streets named after forgotten homelands or the honored dead and narrow alleyways where refugee houses sat hunched in the shadow of six- or seven-story apartment buildings. Sometimes they felt as if they carried city squares with broken benches, churches and graveyards and old outdoor cinemas that had been turned into supermarkets or nightclubs.

They carried so many images and voices, of the living and of the dead.

All of them, some more than others, carried a deep hatred of politicians and doctors and the civil servants who worked at the Social Security office—for anyone they could blame for the fact that they were out here tonight like bums on the sidewalk in the freezing cold far from their homes.

Two or three carried a deep hatred of themselves, for being so small and insignificant.

One carried his hatred of god who had proven himself to be even harsher and more unjust than people.

They carried the weight of their weakness, the weight of time, of the sicknesses that ate at their bodies.

Above all they carried a silent fear and a secret longing for the day that was dawning and all the days that would dawn after that.

So, I think it’s interesting in that no characters are named, they’re all given numbers, but I think that you get a sense of where this short story collection moves, really. It gives an overall sense of it. And of course, I guess you’ve read Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried?

Ikonomou: Yes, obviously.

Germanacos: I guess so. Otherwise it would have been a miracle that it came up. But you made it Greek. That’s the first time I’ve read it aloud, and it has its own—it reads so well in English. And I guess that’s Karen Emmerich’s part to some extent. Let’s move away from what we just read now, I just have some questions for you. This first came out in 2010, didn’t it?

Ikonomou: Yes, in Greek.

Germanacos: So that was six years ago. So the situation in Greece was different than it is now. How was it received? That’s my question, really, how was it received and what has been the public’s response to this book?

Ikonomou: You know, I began to write this book in late 2003 or early 2004, so it took me about almost seven years to finish. I’m a pretty fast writer, as you can imagine. So when the book came out in 2010, a lot of people in Greece thought that this was some kind of prophetic book. I mean, when I wrote these stories, there was no crisis in Greece. Back in 2004, we had the Olympic Games and not all these other things. So some people, many people actually, thought that there was some kind of prophecy in this book. But of course I’m not a prophet.

Germanacos: We don’t know. You wrote the book!

Ikonomou: Yes, but the main thing is that I’m trying always to keep my eyes and my ears open to what is happening around me. So back in 2004 there was a kind of excitement all over Greece, you know, there was this fake prosperity and all these things. But for me, I had the sense back then that something was wrong, something was not right. So what I tried to do by writing this book is to scratch the surface, go beyond the surface of things, and go deeper, and explore the darker corners of the situation in my country. But the main thing is that I didn’t want to write the book only for the crisis in Greece.

Germanacos: Well it sounds like you weren’t addressing the crisis at all, because you wrote most of this before. So it’s what you saw, and it is prophetic in some way. It came true, somehow.

Ikonomou: Unfortunately, yes.

Germanacos: But also, the book came out as we were moving more toward the crisis, I suppose. Were any of these published on their own before the book came out?

Ikonomou: No, no. Just one of the stories, but it was pretty different and had another title… And the main thing for me is that I didn’t want to write a book about the crisis. I’m always trying to reach out to other people, to go beyond the walls of my language, my country, my history, and all these things, and to relate my stories to people all over the world. I’m trying to write about the so-called human condition, and the Greek crisis for me is not just the background, but the framework of this book.

Germanacos: Yes, and it is. It goes beyond the crisis, in other words. It goes far beyond the crisis. It will touch people who are not part of that crisis.

Ikonomou: I hope so.

Germanacos: Well sure, that’s why it needed to be translated into English. And that’s why we’re all lucky to have it. For me, I’m just going to tell you two things: I used to teach writing and modern Greek literature, in Greece, to our students, and after a while, I stopped teaching that and I taught writing, and I taught American stuff, because I didn’t find any modern Greek literature that was interesting enough. I’m no longer teaching those students, but when I read this book I wished I had those students in front of me again, because this is the book that I would want to teach them. American students in Greece would learn about Greece and the world through this book. That was my feeling. At the same time, it opened Greece and Greeks back up to me. It made me empathize and compassionate in a way that I had sort of closed off, in some funny way. So you as a writer—that’s what we want writing to do, right? To open up, to allow us to imagine the lives of others, and that’s precisely what this book did for me. And I really needed it. At this point, because of where Greece is, we get all sorts of funny views of what Greece is and what Greeks are, through the news and the newspaper, what we see on TV, what we might imagine when we think of a holiday in Greece, and this is the most real and authentic sense of Greece and Greeks that I’ve had in many, many years. So I thank you for that.

Ikonomou: You’re welcome.

Germanacos: It’s very meaningful. So who are your influences? And when did you first know that you were a writer?

Ikonomou: I don’t.

Germanacos: You don’t? You’re still not sure? No?

Ikonomou: I don’t use this term when I’m talking about myself.

Germanacos: Okay, when did you start writing a lot?

Ikonomou: I don’t know, since I was 14 or 15, or something like that. I had this kind of journal—not a diary, exactly. It was something that… I didn’t have many friends, so I wanted to talk with someone. And so I invented many imaginary friends and I had this dialogue with them in my notebook. And at some point I felt that maybe it was better for me, more interesting, to start to give some kind of face to these imaginary friends, and that’s how I started to write short stories. I’m trying to write every day, but the main thing is that, actually, I don’t write. I rewrite. And that’s why it took me almost seven years to finish that book, and four years for the next book. I’m trying to write things that have some kind of meaning, and not just stories. They have some kind of moral background, a moral base. I’m trying to write about matters of life and death. That’s what I’m interested in as a reader, and that’s what I want to do as a writer.

Germanacos: When was the first time you showed something you’d written to someone else? Because it sounds like, in the journal, it was between you and you. But when did it go beyond that?

Ikonomou: The first time I showed something I wrote? That was when I was 30 years old, I guess. To my wife. She was my first reader, and for a long time the only reader.

Germanacos: And now how many languages have your books been translated into?

Ikonomou: I’m not sure. Six or seven? I think it’s something like that.

Germanacos: And we were talking a little bit earlier, but this translation, working with Karen Emmerich, how was that, and what was the process?

Ikonomou: She’s the best of my translators, because she didn’t drive me crazy with all these questions. I’m a translator myself, so I know that sometimes it can be really… But with Karen, it went very smoothly. We met just once, in Athens, we talked about the book for about half an hour, it was all right.

Germanacos: That’s pretty amazing.

Ikonomou: Yes. And I think she did an amazing job. And you know, some of the American readers told me that they thought that this book was written in English. And I think that is the biggest praise that a translator can hope for. I feel grateful for that, to Karen.

Germanacos: What do you translate from and into?

Ikonomou: I have translated about ten books of fiction, American and English. Tobias Wolff, D.H. Lawrence, Nabokov, things like that. Faulkner.

Germanacos: Carver? Denis Johnson?

Ikonomou: Denis Johnson, no. Carver, Tim O’Brien…

Germanacos: Huh, that’s very interesting.

Ikonomou: Cormac McCarthy, but not a whole book, because it’s…

Germanacos: That’s interesting because, as I was reading, I heard these other voices. I heard reverberations, a little Carver, a little Denis Johnson, and I wondered what the relationship was. Are those reverberations in the translator’s head, or are they in yours? And it’s very interesting that you’ve translated them into Greek, and that it’s had its influence, I suppose.

Ikonomou: I have a great respect for many American authors. What I like about them is that their writing is straightforward and immediate, and that’s what I like. Because you can’t always find this thing in Europe, in European literature, and I like that very much in the best of the American authors. But after reading literature for, I don’t know, 30 years now, at some point it’s very difficult to distinguish between the voices in your head and your own voice. The books I have read, it’s part of myself, it’s part of my experience in this world. I have read so much that–

Germanacos: You don’t know where one stops and you begin.

Ikonomou: That’s right. And that’s one of the magical things in literature. It becomes part of your own experience and your own presence in this world.

Germanacos: What are you writing right now?

Ikonomou: Nothing.

Germanacos: Nothing? Because you’re traveling?

Ikonomou: No, because…

Germanacos: What’s your last book? It came out in 2014?

Ikonomou: Yes, I—it was not a very wise thing to do—I’m trying to write a trilogy of short stories. So I’ve done the first part, and now unfortunately I have to do the second part. Because I’ve promised to do that. It takes me… I don’t even want to talk about it. I’m a very, very slow writer. Because I pay too much attention to what I write, I have this bad habit.

Germanacos: So you write it, and then you go back over it, and over it, and over it?

Ikonomou: Yes. The main thing is that when I write a short story, I need a lot of time to believe what I write. I have to believe that what I write is true. Not real. Reality is different from truth. So I have to believe my own stories, and that takes me a lot of time. I don’t care for… what’s the word? [Speaks Greek]

Germanacos: Identity? Identification?

Ikonomou: Identification, yes. I want to connect with, not to identify myself with them. And that takes a lot of time, to believe my own story. I have to put a lot of faith in these—I don’t like the term “characters.” I prefer to see them as human beings.

Germanacos: Friends. Your imaginary friends.

Ikonomou: They are not always nice people; I’m not sure they’re my friends. But yes, I have to believe what I write, and that’s the most difficult part of writing for me.

Germanacos: Is it getting harder, easier, or the same?

Ikonomou: It’s getting harder. Because I’m always trying to do something better. I always have higher ambitions and expectations.

Germanacos: Who are you reading these days?

Ikonomou: Who?

Germanacos: What books? What authors? Or what are you interested in? What are you thinking about?

Ikonomou: The fact is that I don’t read too much fiction these days.

Germanacos: That’s okay. You can read other things. It’s all right!

Ikonomou: We’re only a few people here, so I can say that.

Germanacos: You can admit it.

Ikonomou: I have to do some kind of research for my next book, so I’m reading a lot about history and religion—Christianity especially, but I read books by non-Christians. But literature, I have put it aside for now.

Germanacos: Did you do research for this?

Ikonomou: Not really, no. Not in the classic way, but yes, I guess I did a lot of research.

Germanacos: Did you write one story, finish it, and then go on to the next?

Ikonomou: Yes. I have this story, I don’t even want to spell its name anymore because I have written it 17 or 18 times.

Germanacos: And you don’t go on to another story until you’ve finished?

Ikonomou: No, no, I have to finish it. Because I cannot sleep at night if I don’t finish it. I have to do that.

Germanacos: You don’t even want to spell the name?

Ikonomou: It’s the third story, I think, “Mao.” The longest story. I have in my desk 17 or 1 different drafts.

Germanacos: So do you write by hand?

Ikonomou: Yes, I do. Always. Pencil and paper. Afterwards I have to type.

Germanacos: With two fingers?

Ikonomou: Yes. Publishers don’t accept…

Germanacos: Handwritten in pencil, no. Not anymore.

Ikonomou: Not anymore, unless you are some famous writer.

Germanacos: Maybe not even. Do you have a favorite question that you like answering? I know you’ve had some bad questions along the way…

Ikonomou: They were not bad questions! It’s just that this is my first time in the U.S. And earlier this week we were touring Boston University, and the first question that I was asked on American soil is “are you religious?” So that’s the first question, and the second question is “do you love animals? Do you have pets?” Very American.

Germanacos: I guess. But having warned you now, I’ll invite your questions. But you know what not to ask, at least.

Audience Member: Why pencil and paper? I’m not a writer, so I don’t know.

Ikonomou: I have to have this physical connection with writing. I can’t do that by typing. I mean, eventually I have to type, but it helps me very much to understand what I’m writing. I think there are not a lot of people anymore who do that. I teach some creative writing lessons back in Athens, and most of my students are young men and young women in their twenties, and they write their exercises, some of them, they write on their phones. I don’t understand that. I have to have this sense of touching. The screen is very elusive for me.

Audience Member: Do you have a routine when you write, like in the morning, or the afternoon?

Ikonomou: All of my writing is a routine. Yes, as I said earlier, I’m trying to write something every day, even if I know that the next morning I will throw it away. But it’s quite difficult for me because my books cannot pay the bills. So I work as a journalist too, and as a translator, and I do these writing lessons… But I’m trying to find the time to write every day. Late at night. Very late at night.

Germanacos: And with cigarettes.

Ikonomou: With a lot of cigarettes and a lot of coffee. But not every night.

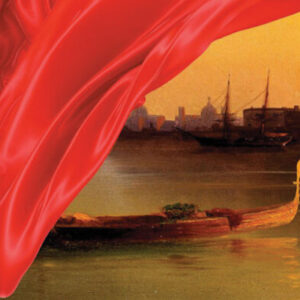

Audience Member: You mentioned for this book the sort of interior research. So I’m wondering, for the city that the book takes place in, how much of that is based on memory, or experience, or composites of actual space?

Ikonomou: The stories are set mostly in the working-class neighborhoods around Piraeus. It’s the largest port in Athens. I lived there for, I don’t know, 30 years. So this is my place, I know what’s going on, so it was easy for me. I didn’t have to do any research on the geography or the society… You know. But the main thing is that, as I said earlier, I need time to get to know the people I write about better. I don’t want my characters to be versions of me, tiny, tiny, tiny Ikonomous. I don’t care about that. And that is something also that takes a lot of time for me. Because the magic thing, one of the reasons I write, if I can find some specific reason, is that I have this sense of freedom. It’s like an out-of-body experience. By writing I become somebody else, I’m somewhere else, doing something else. Not me. That’s, I think, what literature is all about. I mean, that’s the same experience as a reader. Some of my favorite writers are Americans, but this is my first time in America; I don’t know many things, I have never lived here for long, it’s not … [speaks Greek].

Germanacos: It’s not his mother tongue.

Ikonomou: My mother tongue. But I can relate to what they write. That’s because by using their imagination, they help me to…

Germanacos: To use yours.

Ikonomou: So hopefully, that’s what I’m trying to do.

Audience Member: It definitely comes through.

Ikonomou: Thank you very much. You’re very kind.

Germanacos: Such diverse characters. They really are. Or, we won’t call them characters, because you don’t want us to. And you had a question?

Audience Member: Yeah, first off, I read the collection and it was so beautiful. So thank you.

Ikonomou: Thank you very much. San Francisco is my favorite.

Audience Member: My question was, I’m wondering if you felt any sort of internal pressure in knowing that for a lot of people, especially in America, this would be their snapshot of Greece? And I’m wondering if there was any time that you would run into the trouble of trying to capture something authentically for Greece versus what would work best for the story? Kind of the tension between writing a really good short story but also wanting to represent Greece accurately.

Ikonomou: It’s a very interesting question. You want an answer, right? Yes, I have this internal pressure all the time. Because here in America, and in Germany, and in Italy, and in France, in all these places where the book has been translated, it’s natural to read these stories… [Speaks Greek].

Germanacos: Through the prism?

Ikonomou: Through the prism of the crisis. So I have to explain every time that this is not a book only about the crisis. Because, again, when I began to write it, there was no crisis. But I understand that. And I’m trying every time to explain that—which is not something that I want to do, because it sounds a little bit like me talking as a teacher—I’m trying to explain that maybe you have to go a little bit deeper in the book, and not stay only at the surface of the narration. Start to dig a little deeper. There are other things, too. I know that because I’ve written them. But there’s no literary police, I mean, everybody is free to get what she or he can get from a book. But again, I am insisting very much on this, it’s not a book just about the crisis.

Germanacos: It’s both fortunate timing and unfortunate, isn’t it? It’s unfortunate, in a way.

Ikonomou: Yes, that’s right. Yes.

Germanacos: I guess you have to keep answering that question.

Ikonomou: All the time, yes.

Audience Member: What I found perhaps most interesting in reading the book in Greek, Christos, was your extraordinary ear for the vernacular. I don’t think I’ve read a Greek prose writer since Costas Taktsís—and that was 60 years ago, almost, since his novel—who captured the cadence, and the vocabulary, and the idiom of spoken Greek by the semi-literate working-class poor. Do you spend, or did you spend a lot of time listening—in the street, in coffeehouses, in shops—to people talking? How did you get this ability to reproduce this language so well?

Ikonomou: I do, yes. But I guess also that it has something to do, as I said earlier, with the fact that my first serious attempt at writing was by writing dialogues. So maybe it has something to do with that. But, of course, I have my ears open all the time. That’s what I call a “writer’s conscience.” Everything can be the basic idea for your next short story, so you have to be awake all the time. It’s not a very easy thing to do. But, of course—I know this is not a very wise thing to say in public—but I hear voices in my head all the time.

Audience Member: This might be related. I haven’t read the book yet, but I was just in Piraeus, back in February, for about three days. It’s hard to catch a ferry in the wintertime. And I just wondered if your intent in the book was to try and capture the spirit of that place. Because I found it a very interesting city, and completely overlooked because people are just passing through there. And I wondered if you were exclusively focusing on characters here, or if you were trying to convey a sense of that place, also.

Ikonomou: Yes. I tried to do that. But also, I didn’t want to… [Speaks Greek].

Germanacos: To limit it?

Ikonomou: To limit it. But that’s a very interesting thing you say, because a lot of Greek writers, they don’t pay attention to Piraeus because it’s a little bit of a forgotten place, as you said, it’s a place that you can pass through. So yes, of course, I tried to focus—but at the same time, I didn’t want to do something like just a chronicle… I’m always trying to have a wider perspective. So I used—maybe, I guess, in retrospect—I used this place as a base to open up to…

Germanacos: Like Faulkner! Right?

Ikonomou: Faulker… Again.

Germanacos: You eschew the comparison?

Ikonomou: Yes…

Audience Member: I was wondering, you mentioned sort of forming a moral base for the stories, and what that means for you? And is that affiliated with your work as a journalist? Maybe a better question is how morality plays into your job when you write a story, or how you think about that?

Ikonomou: You know, in Greek, there is a very sharp distinction between… [Speaks Greek].

Germanacos: Ethics and morals? We don’t have it in English.

Ikonomou: Yes, so the morality thing, I’m not very interested in it. But I care about ethos. I don’t know if there is an exact word for it in English. What I’m thinking about is that I would like my stories, my writing, my work, to show what it means to be human in a world that rapidly changes in a not very human way. That’s the moral base I’m trying to convey. For me, that’s literature, that’s the most important thing. So I don’t care, again, to write a good story. Yes, of course, it’s a very important thing. But I don’t want to stop there. I’m trying to do what the great books have done to me. I want to make a mark on readers’ hearts and minds, a mark that will last forever. Because that’s what the great books have done to me. I have them in my heart, in my mind, in my soul. And that’s my higher ambition. This is a kind of moral aspect to reading and writing. I don’t know if it’s convincing, all these things I’m saying…

Germanacos: Well those of us who are here, I think we probably wouldn’t be here if we didn’t go along with that. Are there any more questions?

Audience Member: Have you encountered any aspects of the books that you’ve read from American authors here, now that you’re here?

Ikonomou: You cannot even imagine how tight this schedule is. I mean, east coast, west coast, in eight or nine days. I’m just, you know, airport, hotel, airport, hotel, airport, hotel. I haven’t seen many things. But you know, we’ve been in Boston, Rhode Island, Oregon, San Francisco, back in New Jersey, then New York… So I’m pretty sure that, back home, I will have to think a lot. I’m keeping all these notes all the time, because there are so many images, and sounds, and faces, but I don’t have the time to process them. I have this anxiety because I’m in front of people and I don’t want to talk about my books and myself all the time. So yes, the main thing is to pay attention to the books, not to the people who write them. Writers are big liars, too. With one sole exception, you must understand. He’s here tonight.

Image: post card of Saint Spyridon Church, Piraeus, 1887.