Books Making News This Week: Awards Season Begins

From the Man Book to the NBA

Awards season begins. Drumroll as the National Book Awards announces its 40-book longlist one category at a time in The New Yorker this week, shining the spotlight on Hanya Yanagihara’s second novel, A Little Life, and two newly released books—Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies and Susanna Moore’s Paradise of the Pacific. Drumroll as Yanagihara and Marlon James make the Man Booker prize shortlist. In other news, Pulitzer awarded critic Margo Jefferson’s memoir Negroland hits a nerve, drawing intriguing critical assessment. (Frivolity footnote: Jonathan Franzen gets the giggles on Minnesota Public Radio—and apologizes: “Sorry. It’s so… gauche.” And loses it again. “So sorry, it’s so unprofessional… I love St. Paul…”)

Hanya Yanagihara, A Little Life

This week Yanagihara’s second novel is named to both the National Book Award longlist and the Man Booker prize shortlist, triggering a frenzy of backtracking to previous reviews and speed reading for those critics who had yet to read the 720-page book.

The New Yorker announces the National Book Award fiction finalists and reminds us of Jon Michaud’s review, which concludes, “A Little Life feels elemental, irreducible—and, dark and disturbing though it is, there is beauty in it.”

Stephanie Hayes kicks off The Atlantic’s weekly commentary on the six Man Booker finalists. Hayes calls A Little Life a “relentlessly bleak 720-page novel,” a novel “so intense that I found I could read it only in 50-page snippets—and preferably not while sitting by myself. The novel is revolting yet absorbing, psychologically unrealistic yet often emotionally compelling, and at turns completely predictable and shocking. Every dose left me reeling, as did the whole.” (Earlier in The Atlantic, Garth Greenwell dubbed A Little Life “the most ambitious chronicle of the social and emotional lives of gay men to have emerged for many years.”)

Alex Preston (The Guardian) admits he “spluttered often” while reading A Little Life over an intense three-day period, adding, “it is a book that teeters regularly over the abyss of ridicule. The friends’ successes are the absurd dreams of a teenager; the quality of the writing is decidedly mixed, with many an ugly sentence; it is a humorless novel, even when it tries to be funny.” But in the end, he concludes, “it is the very relentlessness that makes this a book unlike any other I’ve read. The novel is brilliantly redeemed by Yanahigara’s insistence on Jude’s right to suffer… A Little Life asks serious questions about humanism and euthanasia and psychiatry and any number of the partis pris of modern western life. It’s Entourage directed by Bergman; it’s the great 90s novel a quarter of a century too late; it’s a devastating read that will leave your heart, like the Grinch’s, a few sizes larger.”

Christian Lorentzen (London Review of Books) takes a contrarian stance. “The novel’s opening signals that it will be a male millennial take on Mary McCarthy’s The Group,” he writes. “But something sets Jude apart from his friends. He walks with a limp, suffers from episodes of severe spinal pain and will say nothing to his friends about his life before college. He cuts himself.” Of Jude, Lorentzen writes, “I found Jude an infuriating object of attention, but resisted blaming the victim. I blame the author.”

Lauren Groff, Fates and Furies

Newly longlisted for the National Book Awards, Fates and Furies, which started off last week with a bang, gathers steam, with particular attention to Groff’s innovative use of the dual narrative of a marriage.

Laura Miller (Slate) explores Groff’s choice to combine two small novels, the his and hers perspectives on the long marriage— “a little like Evan S. Connell’s Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge.” She continues: “Two people sharing the same home and what seems to be the same life can occupy entirely different planets, storywise; two very different short novels can, bound together, explore the way we use stories to get what we need to make sense of our own lives and others’.”

“The half-and-half narration could’ve failed terribly,” writes Jason Sheehan (NPR), “if Groff hadn’t had it in her to do the hard thing—which is not to just tell two versions of the same story, but two completely different stories that happen to contain some of the same details. But she did. A long marriage isn’t just about two people remembering things differently, she says with her choices. It’s about two people remembering entirely different things, inhabiting entirely different worlds.”

“For all the homage Groff pays to the comforting rituals comprising a marriage, her novel is also attuned to how little we’ll ever know, even of those we know best,” notes Mike Fischer (Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel). “And not just about our partners, but also about our families and friends—often as surprising and conflicted here, in ways good and bad, as Mathilde.”

Elaine Teng (The New Republic) credits Groff’s “rich, energetic prose” for keeping Fates and Furies afloat, adding, “it’s a testament to her abilities as a portraitist that Lotto, and especially Mathilde, are fascinating individuals, even if the novel doesn’t quite come together as a whole. Groff explicitly treats the marriage as a third character—‘Between his skin and hers, there was the smallest of spaces, barely enough for air, for this slick of sweet now chilling. Even still, a third person, their marriage, had slid in.’ But in a novel so focused on the two protagonists, there isn’t room for the third character. The marriage arc is subsumed in their individual stories, shaped by their families, and the parts outshine the whole. Lotto and Mathilde are meant to illuminate each other, but they are brighter on their own.”

“Fates and Furies is no ordinary domestic novel of the pearls and pitfalls of one particular marriage,” concludes S. Kirk Walsh (San Francisco Chronicle). “It’s a dazzling showcase of lyrical writing and inventive storytelling.”

One of Groff’s most effective tricks, Connie Ogle (Miami Herald) points out, “is voicing a Greek chorus of sorts that comments parenthetically. Lotto ‘didn’t deserve these women who surrounded him. [Perhaps not.]’ His sister Rachel embraces a punk aesthetic at 10: ‘She understood it was better to be weird than twee. [Smart girl.]’”

Marion Winik (Newsday) credits Groff’s “musical, nearly magical writing” for carrying the “twists and turns” of her complicated plot.

Marlon James, A Brief History of Seven Killings

Jamaican author Marlon James’s third novel garnered a series of honors last year, as a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle (board member Carolyn Kellogg’s review on Critical Mass here) and winner of the Anisfield-Wolf book award. All grist for further discussion as he gains a spot on the Man Booker shortlist.

A Brief History of Seven Killings, which spins around the 1976 assassination attempt on Bob Marley, is already awash in rave reviews, including this from The New York Times’ Michiko Kakutani: “It’s like a Tarantino remake of “The Harder They Come” but with a soundtrack by Bob Marley and a script by Oliver Stone and William Faulkner, with maybe a little creative boost from some primo ganja. It’s epic in every sense of that word: sweeping, mythic, over-the-top, colossal and dizzyingly complex. It’s also raw, dense, violent, scalding, darkly comic, exhilarating and exhausting—a testament to Mr. James’s vaulting ambition and prodigious talent.” And this from Zachary Lazar (New York Times Book Review), who compares the novel to David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, concluding, “A Brief History of Seven Killings eventually takes on a mesmerizing power. It makes its own kind of music, not like Marley’s, but like the tumult he couldn’t stop.”

Sean Carberry (The Irish Times) says the novel is “not for the faint-hearted,” and calls out “the extraordinary dialogue which permeates the book and sets its unorthodox tone.”

“James’s sprawling, daunting, messy effort is a great—if grim—success,” concludes Randy Boyagoda (The New Statesman).

Susanna Moore, Paradise of the Pacific

Moore, author of seven novels, grew up in Hawaii and left at 17. She returns in Paradise of the Pacific, newly named to the National Book Award nonfiction longlist.

Jan Morris (New York Times Book Review) is an admirer, calling Moore’s book “an astonishingly learned summation of the Hawaiian meaning, elegantly written, often delightfully entertaining and ultimately sad.”

Peter Lewis (Christian Science Monitor) also praises Moore’s book as a “stately and graceful history… here to entertain, effortlessly, and to instruct, slightly more demandingly.”

For Ellen Emry Heltzel (Seattle Times) Paradise of the Pacific is “that rare book about Hawaii that will resonate with the serious reader, especially those who have been there and can compare Moore’s meticulous account to the version of native culture that’s delivered to tourists now.”

“Moore traces a lineage that, for better and for worse, has made contemporary Hawaii what it is,” writes David Ulin (Los Angeles Times). “’With the arrival of foreign explorers, navigators, seamen, and merchants,’ she tells us, ‘the fixed world of the Hawaiians, governed by a hereditary ali’i and priesthood with a distinctive system of kapu, suddenly became one of flux, if not chaos.’” In many ways, it remains so today.” The power of Moore’s book, “as well as its bitter beauty,” he concludes, “resides in Moore’s ability to lay out this progression as a set of turning points, inevitable from the standpoint of the present, but in their own time more a matter of human ambition and fallibility.”

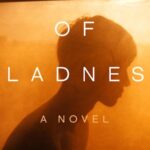

Margo Jefferson, Negroland

The Pulitzer-award winning critic’s new memoir injects a discussion of class into the ongoing debate about the racial divide in the U.S. Jefferson’s title is her threshold: “Negroland is my name for a small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty… I call it Negroland because I still find ‘Negro’ a word of wonders, glorious and terrible.”

Tracy K. Smith (New York Times Book Review) points out Jefferson’s candor, and “the courage and rigor of her critic’s mind.” She compares her to “a number of America’s greatest thinkers on race, many of whom she directly references, refines and grapples with: James Baldwin, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, E. Franklin Frazier. Jefferson also invites women to the round table: Adrienne Kennedy, Nella Larsen, Ntozake Shange, Jamaica Kincaid—and voices outside that established canon, like the contemporary poet and essayist Wendy S. Walters; and Charlotte Hawkins Brown, whose 1941 etiquette handbook, ‘The Correct Thing to Do–to Say–to Wear,’ offered blacks a counternarrative to the one that said ‘perfect mastery of comportment’s rituals . . . like higher education, or high art, it is beyond your capacities.’”

“A vibrant and damning memoir,” writes Hamilton Cain (Minneapolis Star-Tribune). “Jefferson’s method is impressionistic, discursive and often lyrical, revealing the deep divisions of black elites, who have fought silently but stoically against institutionalized white racism even as they’ve remained aloof from lower-income people of color. Negroland lifts the veil from the ‘Talented Tenth,’ striking at the hypocrisies still curdled beneath our conversations about race and class.”

Rebecca Hussey (Bookslut) focuses on the ways in which Jefferson “leads readers to see American history through what will be for many of them a new lens. Through exploring her personal experience of race, class, and gender in America, she complicates our history, doing this with beautiful sentences and a voice that is artfully self-aware.”

Rebecca Carroll (Los Angeles Times) sees Jefferson as “simultaneously looking in and looking out at her blackness, elusive in her terse, evocative reconnaissance, leaving us yearning to know more.”

“Negroland is a veritable library of African-American letters and a sumptious compendium of elegant style,” notes Donna Bailey Nurse (Boston Globe). “The stunning photo on the cover features a glamorous woman in white gloves, a sparkling bracelet, and a gold braid suit. We have only a partial view of her face—only an impression. Which is a good way to describe Jefferson’s unusual prose style throughout. She paints her rich inner and outer landscape with deft, impressionistic strokes. It’s a technique that disrupts convention—which is her privilege after all.”

Roxane Gay’s (Oprah) take on Negroland: “a unique remembrance of a black girlhood shielded by advantage yet exposed to bigotry. Negroland exists to this day, but in a culture where it’s necessary to insist that Black Lives Matter, its borders are far from secure.”

Jefferson’s memoir, concludes Robin Givhan (Washington Post), “is not sweeping or encyclopedic. It is lean, specific and personal. But it is also enlightening.”