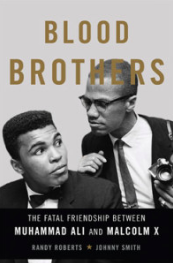

The Night Cassius Clay Beat Sonny Liston

From Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship of Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X

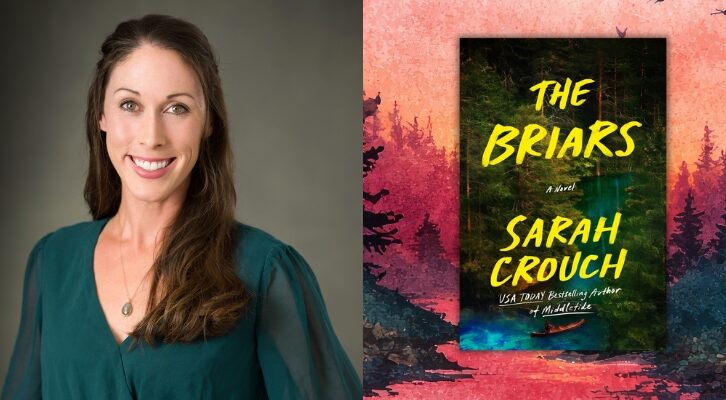

The following is from Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith’s book, Blood Brothers.

Sonny trudged to his corner like an aged sparring partner, collapsing hard onto his stool. His trainer, Willie Reddish, and cut man, Joe Polino, crowded in front of him. Polino immediately went to work on Liston’s eye, sponging it clean and smearing Monsel’s solution, a thick, caustic substance that’s now illegal in boxing, on the wound. Monsel’s dries quickly, leaves a black residue, and can be blinding if it gets into a fighter’s eyes.

Quite possibly another blinding substance was put on Sonny’s gloves. According to Jack McKinney, a Philadelphia sportswriter sitting near Liston and Polino, when Sonny returned to his corner he ordered Polino to “juice the gloves”—that is, smear some illegal substance on the them. In several previous fights Liston’s opponents had complained that a painful astringent, perhaps from Sonny’s gloves, had gotten into their eyes. McKinney claimed that Liston’s corner men had a history of juicing his gloves and did it once again in the Clay fight. “If you look at a film of what went on in Liston’s corner between the third and fourth rounds of that fight,” McKinney told writer Thomas Hauser, “you’ll see Polino in the ring with Willie Reddish standing behind him, blocking everyone’s view. And Polino is at Sonny’s knees, rubbing something on his glove.”

Round four belonged to Clay from start to finish. No longer was he moving in jerky, pogo-stick bursts. Still circling Liston, he maneuvered more slowly, confidently, snapping out jabs that seemed to explode in Sonny’s face. Soon Liston’s right eye had an angry welt under it, and his nose and lips looked like he was having an allergic reaction to multiple bee stings. Sonny tried to respond, but his jabs consistently missed their target and his hooks mostly punished the air around Cassius’s head. Once, however, Liston forced a clinch, and although he could not punish Clay with punches, he rubbed his glove across Cassius’s eyes. If his gloves were juiced, this is when he did the damage.

Several sportswriters thought that Cassius’s jabs connected with the Monsel’s on Sonny’s left eye and that then he transferred the substance to his forehead as he wiped off sweat. The “thin skin of the caustic on his forehead,” wrote Maule, “washed down into his eyes between rounds when his trainer, Angelo Dundee, swabbed him with a wet sponge.” The trouble with this view is that Cassius did not brush his forehead with his left, his primary punching hand, during the round. The only hand that swept across Clay’s eyes and forehead was Liston’s.

Nor did Dundee contribute to the problem. By the time Clay reached his corner, his face was already contorted with pain. He felt like “some acid” was in his eyes. “I could just see blurry . . . it felt like fire.” Blinking as if he were trying to clear grit out of his eyes, he told Dundee that something was wrong. Removing his mouthpiece, he screamed at Dundee, “Cut off the gloves. Cut off the gloves.” At the time Cassius believed that someone was trying to fix the fight. “Dirty work afoot!” he told Dundee. “Dirty work afoot,” he repeated to his other corner men.

Dundee was not about to cut off Clay’s gloves, not in a heavyweight championship contest. He quickly examined his fighter. “I put my pinky in his eyes and then mine,” he recalled. “It burned like hell.” While Cassius complained, Dundee tried another test. He dried Clay’s eyes with a towel, sniffing and tasting it when he finished. “There was something wrong. I tasted a strange substance.” Maybe it was from Liston’s gloves; perhaps it was something else that had been put on Sonny’s body.

Unconcerned with the cause, Dundee focused on the problem. He sponged Clay’s eyes, trying to flush out whatever substance was in them. He tried to reassure him, telling Cassius that the pain would pass and that he would be fine. “If you can’t see, keep away from him until your eyes clear. This is the big one. Nobody walks away from a heavyweight championship.”

While Dundee was earning his wages in Clay’s corner, Black Muslims at ringside had reached their own conclusions about the cause of the problem. Izenberg remembered that Captain Sam and Archie Robinson were out of their seats, watching Dundee wipe Clay’s eyes while he convulsed in pain. They clearly believed that Dundee was the culprit. Seeing the rising anger of the Muslims, Chris Dundee signaled to his brother Angelo to wipe his own face with the sponge, which the trainer soon did, telling Archie and Sam, “Look! Look! Look!”

But before that demonstration, he had a fighter to motivate. When the bell rang for round five, Cassius said Angelo pushed him forward and shouted, “This is the big one, daddy. We aren’t going to quit now! . . . Run until your eyes clear! run!”

As Clay moved forward, half blind and confused, Bundini Brown offered a piece of tactical advice: “Yardstick ’im, champ! Yardstick ’im!” It was the perfect strategy. Often in previous fights, Clay had used his left, held straight out from his shoulder, as a yardstick for measuring distance and punches, and occasionally for taunting opponents. Now he could use his straight yardstick left as a seeing-eye device. As long as Liston remained an arm’s length away from him, Cassius was in safe territory.

Liston eyed Clay at the start of the fifth round “like a kid looks at a new bike on Christmas.” Seeing Cassius’s condition, he rushed forward with cruel intentions. Instead of maneuvering to cut off the ring and force Clay into a corner, he moved directly toward him like an aggressive street brawler stalking a frightened victim. Cassius moved backward, unable to completely avoid Sonny’s bull rushes. But he could grab and hold, thereby denying Liston leverage for his most lethal punches. But in the clinches Clay absorbed frightful punishment. Liston pounded his sides and stomach with combinations. At one point, early in the fifth, Clay grabbed the back of Liston’s neck and Sonny landed sixteen consecutive body blows before the referee broke the clinch.

Clay had no plans for fighting blind. More than other fighters, he boxed in a head-high, wide-eyed style. At times he looked like a painter, stepping back to inspect his work before adding a final dab of color. But now he was robbed of his vision, glimpsing Liston imperfectly through “tear-fogged” eyes.

“Man, in that round, my plans were gone. I was just trying to keep alive, hoping the tears would wash out my eyes. I could open them just enough to get a good glimpse of Liston, and then it hurt so bad I blinked them closed again. . . . He was trying to hit me square . . . it could be over right there.”

There is a widely accepted myth that during the fifth, Clay’s speed kept him out of harm’s way. In truth, during the first ninety seconds of the round, Liston landed scores of punches, to the head as well as the body. Rather than his speed, Clay’s ability to take a punch kept him in the fight. Soon after the match, Clay reflected, “He shook me with a left to the head and a lot of shots to the body. Now, I ain’t too sorry it happened, because it proved I could take Liston’s punching.”

Liston “was snorting like a horse” during his onslaught, Cassius remembered, but by the middle of the round he was breathing heavily through his mouth. Arm-weary and bone-tired, he began to slow, throwing fewer punches, and those were mostly slow, lazy, and purposeless. In the clinches, he rested rather than pulling his arms free and banging Clay’s body. Now, Cassius began yardsticking him and, as his eyes cleared, stung him with sharp jabs. He began to talk. “You ain’t nothing!” And to prove the point, he yardsticked Liston and then slapped him lightly five or six times in the face, almost like a teenage boy play-boxing with a five-year-old, or, wrote Tex Maule, “like a man knocking on a door.”

Sonny had thrown more punches in the first half of the round than he normally threw in two or three, and now his lack of conditioning showed. For Sonny, the bell that ended the round came as a relief, even though it ended his best opportunity to win the fight. Nothing was working. Cassius Clay had weathered Liston’s stare, intimidation tactics, bull rushes, juiced gloves, and best punches. The arm-weary, mouth-breathing champion had nothing left—no plan B, no second wind, no chance.

Cassius had everything the champion lacked. As the result of hard conditioning and the advantages of youth, he felt the rise of a second wind as his eyes cleared and his confidence grew. “Get mad, baby!” Dundee told him. He said to go for the knockout. “No,” Clay answered. “I ain’t in a hurry. Maybe I’ll carry him for the 15.”

Taking his last deep breaths before round six, Cassius knew, “I was going to make Liston look terrible.”

He did. Closing the distance to the champion, boxing at a slower, more deliberate pace, he started to punish Sonny. Steve ellis described the action for the closed-circuit viewers: “We note that Sonny stands flat-footed most of the time. Easy target. Easy!” His voice rose on the second “easy” as Clay landed a punishing jab and a powerful right cross. Although Clay held his hands low, his boxing was classic. Every attack followed from his perfectly timed jab, always aimed at the cuts below Sonny’s eyes. As Liston moved sluggishly forward, Clay jabbed, sometimes softly, as if he was just toying with Sonny, other times with jolting force. Depending on how Liston reacted to the jab, Clay might throw a right cross or a right-left-right combination of hooks. Then he backed away before Liston could set himself to counterpunch. “Sonny can’t seem to slip or knock down that jab effectively,” Ellis said. “Cassius throws it from all angles. Very tricky left lead.”

It was a textbook round. Clay knew that Liston had entered the pain zone, and there was nothing he could do about it. “He was gone,” Clay realized.

Between rounds Cassius twisted around and called to the reporters, “I’m gonna upset the world!” “I never will forget how their faces was looking up at me like they couldn’t believe it,” he said later. But sitting close to the reporters was Malcolm X, and he believed it. He had prophesied it. Throughout the fight he never lost faith, not even when Cassius fought blind in the fifth. Although inwardly Malcolm rejoiced, outwardly he was the picture of tranquility. “I folded my arms and tried to appear the coolest man in the place,” he wrote, “because a television camera can show you looking like a fool yelling at a prizefight.”

While Clay’s confidence swelled, Liston’s deflated like a pinpricked balloon. Willie Reddish had to convince him to sit down at the end of the sixth, and while Joe Polino labored to mend the fighter’s cuts, the normally silent and undemonstrative Sonny jabbered about something. He stayed on his stool after the warning buzzer, and at the bell Reddish turned to referee Barney Felix and made a slight, low gesture with his hands, the signal that his fighter was through, the match was over. Liston remained immobile on his stool, tears mingling with the blood below his eyes.

On his feet at the buzzer, Cassius saw what was happening before Reddish’s capitulation. “I happened to be looking right at Liston when the warning buzzer sounded, and I didn’t believe it when he spat out his mouthpiece. . . . And then someone just told me he wasn’t coming out! . . . It’s a funny thing, but I wasn’t even thinking about Liston— I was thinking about nothing but that hypocrite press. All of them down there had written so much about me bound to get killed by the big fists.”

As Clay looked toward Liston’s corner, he raised both arms high and broke into a jig, floating effortlessly in the center of the ring, before Bundini embraced him in a bear hug. Then, his mouth wide open, he wriggled loose from Bundini’s arms and made a mad dash toward the reporters.

For the record, everyone in Liston’s corner—and later a team of eight doctors from St. Francis Hospital in Miami—insisted Sonny had torn a tendon in his left arm early in the fight. The blood had drained into his bicep and deadened his arm, they said. Sonny had wanted to continue, his manager, Jack Nilon, claimed. “I made the decision. Before Sonny could protest, Willie and I stepped in front of him and waved the referee off. Sonny spit out his mouthpiece and cursed me and cursed Clay.” “I can beat the bastard one-handed,” Liston supposedly said. And perhaps, as unlikely as it seems, he did not play any role in the decision to end the fight while slumped on his stool. Still, the fact that Clay was willing to fight blind and Liston refused to continue because of a sore shoulder tells much about both boxers.

But the moment Reddish signaled Felix that his fighter was done, Sonny Liston became just another bruised, bloodied, beaten ex-champion, looking older than his age, whatever that was, and sadder than any ex-mob goon ever had. Surveying Liston’s face, which looked “like a melon that had fallen off the back of a truck,” Murray thought “it was possible to feel sorry for this mastodon.”

Clay’s gate-crashing sprint for the reporters, however, grabbed all the attention away from Liston’s suffering. He pulled away from his handlers, dodged well-wishers, and “climbed like a squirrel onto the red velvet ropes.” Perched above the multitude, he pointed with a still-gloved hand at the working press and commenced a long-repressed harangue. “I am the greatest!” he shouted. “I shook up the world! . . . You hypocrites! You ought to hang your heads. Eat your words! Eat! Eat your words!”

From BLOOD BROTHERS. Used with permission of Basic Books. Copyright © 2016 by Randy Roberts and Johnny Smith.

Lit Hub Excerpts

An excerpt every day, brought to you by Literary Hub.