An Incomplete Atlas of Fantastic Maps

Susan Daitch on Literature's Attempt to Map the Countries Yet to Come

Maps of the End of the World As We Know It

In the second issue of The Watchmen, the masked adventurers stand around a map of the United States. A close up will reveal geographic regions labeled: Anti-War Demos, Black Unrest, Drugs, Promiscuity, and Captain Metropolis refers to the map as a challenge to the assembled self-described Crime Busters. The map, to some of the Watchmen, symbolizes the fall of the America which they believe they have an obligation to rescue, while others have a more why bother approach. Edward Blake, The Comedian, ignores Captain Metropolis. Facing away, feet on desk, reading a newspaper whose headline reads, France Withdraws From NATO, on the next page he will burn Captain Metropolis’s map. The Comedian likes to confront the Watchmen, to laugh in their faces. He’s a cynic. The reactions to the American map, for the Crime Busters, present a line in the sand. Their responses, early in the series, define the schisms within the group. When they are all aged and retired, it’s the apparent murder of The Comedian that, ironically, revitalizes the group. Rorschach in fedora and trench coat, whose mask is a shifting image of Rorschach blots, believes Blake’s fall from a skyscraper was no accident and uses the murder as a call to galvanize the survivors to action. He calls on them, one by one, but by now they’re old and either too defeated or unconvinced by Rorschach’s conspiracy theories, though the world, as they knew it is coming undone.

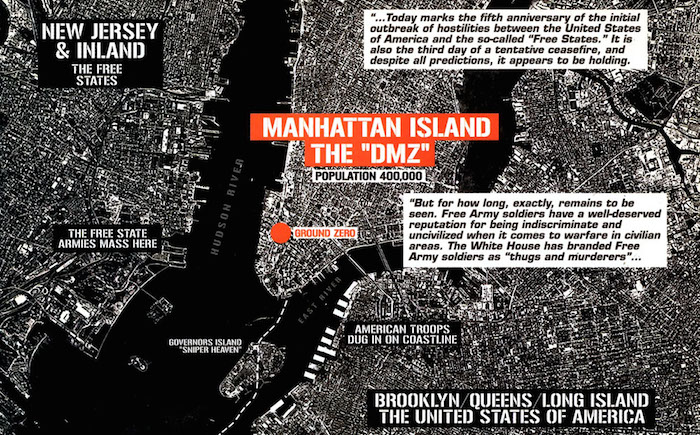

DMZ comics by Brian Wood and Ricardo Buchelli chart post-apocalyptic New York in which superheroes are few and far between. The Free State Armies entrenched in New Jersey and the American Troops quartered in Brooklyn, Queens, and western Long Island are terminal enemies growling and skirmishing across rivers and land boundaries. Matty Roth, a hopeful intern working for journalist Viktor Ferguson, is marooned in the war zone of Lower Manhattan, left by his mentor, a cowardly double-crosser. Roth must make his way through a landscape whose urban intersections are recognizable, but also the winds of Blade Runner blow through the futuristic ruins. He runs into gangs, snipers, extreme weather patterns. There are identifiable street signs, shells of buildings and neighborhoods. Wood and Burchelli use the map of what is known and real, but show us how it can be destroyed, and ad hoc be reconstructed: a hybrid of water tower hide outs and self-sufficient zoos. The land of conjecture starts with an actual map. We can follow Roth’s progress through the knowable and the speculative. He eats noodles with sprigs of chopsticks as neon blinks in Cantonese characters, he travels to the area of the Flatiron Building, Central Park, the Upper East Side, home to the most selfish and shortsighted citizens of DMZ. Roth passes through all of them, then flounders in a bamboo forest somewhere in Central Park. Wood and Buchelli provide the maps so the reader can follow Roth while facing the chaos of war, increasingly violent fratricidal gangs, and a landscape that’s both familiar and uncanny.

Jason Lutes also uses actual maps of Berlin during the Weimar Republic, but the end of the world as his characters knew it was in no way speculative. It was about to happen. The reader knows the period at the end of the sentence. Where Brunnestrasse intersects with Torstrasse, where the Cocoa Kids, a touring African-American jazz band, perform on Bastian Strasse, where journalist Kurt Severing will meet art student Marthe Müller, as a spectrum of characters traverse Berlin, the landscape grows more ominous and unpredictable. There are no escape hatches, no Rorschach or Captain Metropolis to get them out before the elections of 1933. The maps of City of Smoke and City of Stone are blurry, hard to read as if anticipating the map of a soon-to-be-lost city, but insofar as they are readable, they’re accurate. In his interviews with Francois Truffaut, Alfred Hitchcock spoke of his decisions to have the audience know more than his characters. In Secret Agent, based on the Conrad novel, the boy has a package to deliver. There’s a bomb in the box. The audience knows, but the boy does not. He dawdles on the way to his destination, stopping at a carnival, to look in shop windows. Finally he boards a London bus. It gets stuck in traffic. Similarly, we know the bomb that’s ticking for the characters in Lutes’s graphic novels. They don’t have much time left. The fascist-led riots of the Neukölln district in 1927 and Kristallnacht, a few years later, are right around the corner.

As a child Bertrand Russell drew a map of his grandparents’ enormous estate. A version of it appears in Logicomix (Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos Papdemitriou). No and Forbidden are scrawled across rooms he was not allowed to enter, his version of the home “full of secrets and prohibitions.” As far as he knows, his parents have disappeared, and he’s stuck in “The Lodge,” ruled over by a cold, domineering grandmother. One of the secrets in the attic: a mad uncle kept under lock and key. The young Russell finally climbs out a window and over a rooftop to watch his unstable relative. As an adult when he works on a definition of infinity, interviews with other mathematicians who’ve gone mad seem a kind of warning. It’s believed that in trying to articulate that definition, one courts insanity. The definition is infinitely difficult, if not impossible, and the project tethers him to the image of his uncle, hidden away, his room one of the areas of the map labeled: No! The possibly heritable end of the world was madness, and it was personal. The childhood map conveyed the terror of the house, and its secret that would continue to haunt Russell, even as an adult. “In his face I saw the embodiment of what was to become my greatest nightmare… Madness!”

Disappearing Puzzles

Literature is written by and for two senses: a sort of internal ear, quick to perceive ‘unheard melodies’; and the eye, which directs the pen and deciphers the printed page, and let me add as a reader, the internal eye visualizes its color and meaning.

–Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature

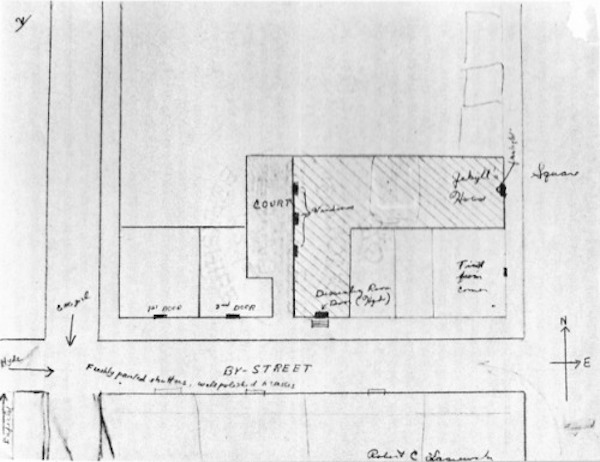

Nabokov understood the seduction of maps as a way of ordering the fantastic, the disorderly, the sometimes contradictory nature of description, a visual aid to the internal eye. He mapped as a reader. He mapped Sotherton Court and Mansfield Park. He mapped Gregor Samsa’s apartment which the bug could no longer leave without smashing his shell, and therefore himself, but when he arrived at The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, there was the doorstep of the architecture of good and evil. How will an ordinary London doctor, by his own choice, turn himself into a monster?

Robert Louis Stevenson provided detailed descriptions of the house, but corridors, labs, sitting rooms, courtyards, and doorways aren’t easy to visualize. Now we have an infinite number of images for the word “laboratory.” But to a contemporaneous reader, how important was it to visualize what he or she read?

I’ve read over Stevenson’s description of the path Jekyll/Hyde took to get from the surgery to the courtyard, but it’s not straightforward, picturing this place. The door to the laboratory might be street level. The university physics laboratories where my father and the fathers (It was always fathers, not mothers, in that time and place) of my childhood friends were always in the back of the buildings and possibly upstairs, not so easily accessed as a kind of storefront. The biggest transformation that went on in them was the disappearance of the slide rule, replaced by big lumbering computers. A street level lab where you open a door and walk in? No security? No ID? The film sputters in the projector. I’m having trouble here.

Nabokov, whether he’s one hundred percent accurate or not, managed to draw a viable map. The house contains secrets that can’t be contained. If, in the gothic, the house equals the unconscious, not the realistic, it’s as if Stevenson is saying: good luck with that because the house makes no sense. But Nabokov wanted the Jekyll story to make sense, to have spatial authenticity, coherence. Nabokov’s map sorts and clarifies. The Jekyll dissecting room is in the foreground, the Hyde residence is in the back. He wrote, “The relationship of the two are typified by Jekyll’s house which is half Jekyll, half Hyde.” A charming mews is also a degraded courtyard where “a fantastic drama passes in the presence of sensible men.” Nabokov’s mapping of Jekyll and Hyde orders the comings and goings, allows for the passage of the fantastic. We become believers.

From Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature.

From Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature.

According to Georges Perec Image, (Jacques Neef, Hands Hartje, Éditions Seuil, Paris 1993) when the Oulipian wrote Life: A User’s Manual, he kept a Sol Steinberg drawing of a New York apartment building above his desk as he wrote. The façade has been peeled away so you can see people having meals, reading papers, typing, sleeping as if peering into a dollhouse. The cartoon and the maps Perec drew as he worked were important to navigating Life: A User’s Manual, composed of the stories of the residents of 11 rue Simon Crubellier, a large apartment building in Paris. Each of the 99 apartments as well as corridors, stairways, boiler and basement storage rooms is given a chapter, and each space was occupied and animated by at least one character. Perec provided a map in the novel itself, so readers can follow as pieces of stories fit together like the jigsaw pieces that puzzle-maker Gaspard Winkler (occupant of apartment on the sixth floor, right) constructed for wandering painter Percival Bartlebooth (third floor, left). Once Bartlebooth completed the 750 piece puzzles made of his paintings, he had them treated so the shapes of the pieces would be undetectable, then the colors are removed, so blank paper returns. Rémi Rorschach, a television producer (fourth floor, left) who has his own story of global peregrinations and erasure, wants to make a film about Bartlebooth’s project. Bartlebooth turns him down, he would prefer not to.

Readers of Perec have roamed the 17th arrondissment and scoured Paris archives looking for 11 rue Simon Crubellier. I consulted Jacques Hillairet’s 1956 Connaissance du Vieux Paris, but in the index, rue Sibour is followed by rue Simon-le-Franc. I also looked on my father’s maps of Paris circa 1947 or so, maps I also once used to try to find the de Broglie lab where he had worked. No luck with either. Rue Crubellier vanished with Perec, not to be found anywhere. The street, like Bartlebooth’s paintings, is unmappable and has erased itself.

Hornerites and the Phantom Islands

The image you see when you open George Saunder’s The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil is a map of the disputed Horner (Inner and Outer) territories: West Distant Outer Horner, Far East Distant Outer Horner, Short Term Residency Zone, complete with reverse compass rose. North is down, south is up, east and west are switched. There is enough space in Inner Horner for one steampunk assemblage of a citizen to stand, but since there are seven of them total, the Inner Hornerites have to rotate turns taking up residency in their nation. The other six, in the interim, have no choice but to wait within the boundaries of Outer Horner. Spurred on by the ascendant dictator Phil, the Outer Hornerites begin to interpret the waiting Inners as an invading force, pure and simple, and so they lay claim to the land and meager resources belonging to the tiny minority in their midst.

The Saunders’ map, with its cartographical detail, kilometer scale, and calibrated contour intervals, represents the absurdity of the aggressions Phil and his followers will find all kinds of reasons to justify and celebrate. Phil’s frightening reign could stand in for any actual colonial enterprises. Tolkien’s Middle Earth might be one of the most well known of all fictional maps of fictional places, and a debate goes back and forth about the Dark Lord Sauron and the creatures of Mordor. Were their encroachments into the Shire and other provinces, all followable on maps, meant to represent the rippling advance of the Iron Curtain or the Anschluss? Saunders maps out how a tyrant whose brain is precariously mounted on a sliding rack and who craps machine oil when depressed, is able to take over, similarly, without pointing to one identity card or another, but at what the map says. The absurdity of blind faith can take many forms.

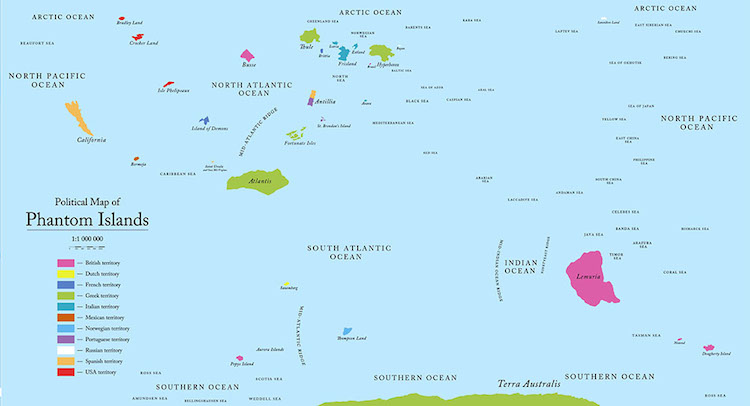

Though they aren’t stories or books in the traditional sense, Agnieszka Kurant’s maps reconfigure combinations of actual places, works of art hinting at fictions. In Political Map of Phantom Islands (below), seas and oceans form one Pangaea-like body of water dotted with Atlantis, Thule, Antillia, a carrot-shaped wedge labeled California and other islands, all color coded according to who owns which pieces of land. Greece claims Atlantis and Hyperbolea, England controls Lemuria, Frisland is French, and so on. This is what would be left in the event of massive global warming, extreme levels of water rising so that much of what is now land is submerged. In the imagined but possible cataclysm, some of the islands are known, others are mythological. What does it mean to be a phantom but to still have potentially reliable co-ordinates? Kurant is interested in the detritus of capital, the tossed aside. To produce The Archive of Phantom Islands Kurant wrote, “I researched nonexistent islands that have appeared on important political and economic world maps throughout the history of cartography. In some cases, these islands were results of mirages; in others, they were inventions, purposefully added by explorers to acquire funding for further colonial expeditions. Many of these territories were sources of real financial transactions and conflicts that almost led to wars.”

Kurant’s documentation seems entirely viable, the stuff of any GPS system or AAA map, but also of the world of Treasure Island. As Pop famously says in the Firesign Theater’s Nick Danger episode, “you can’t get there from here.” It’s impossible to actually step onto the Phantom Islands or DMZ’s New York, but there is something tantalizing and uncanny about these maps to the imaginary. They offer a way of reading, providing some kind of working gravitational pull to the magical film that runs in your head as you read.

Susan Daitch’s new novel, The Lost Civilization of Suolucidir, is out now from City Lights.

Susan Daitch

Susan Daitch is the author of five works of fiction, and her work was the subject of an issue of "The Review of Contemporary Fiction" along with David Foster Wallace and William Vollman. She has been the recipient of two Vogelstein awards, research grants from NYU, CUNY, was awarded a 2012 Fellowship in Fiction from the New York Foundation of the Arts. Her novel, L.C., won an NEA Heritage Award and was a Lannan Foundation Selection. Her latest book, The Lost Civilization of Suolucidir, is out now from City Lights. She lives in Brooklyn with her son and teaches at Hunter College