Against Lousy Holocaust Novels…

…And in Praise of the Unsung Masterpiece We Have to Blame for Them

If you read much, or really any, contemporary American fiction, the genre of lousy Holocaust novels is surprisingly difficult to avoid. The telltale signs of a lousy Holocaust novel are many, and in most respects they resemble those of all other lousy novels: one-dimensional characters, cardboard backdrops, implausible plot twists, unambiguous conflicts—and most of all, the absence of any challenge to the reader, whose expectations are gleefully enforced at every turn. Adorable child? Check.

Hardhearted villain? Check. Feisty heroine? Check. Dramatic setting? Check. Conflict where we know who to root for? Check. Uplifting ending? In most American Holocaust novels, check!

I have nothing against lousy novels. (Without them, how would producers get ideas for lousy movies?) But lousy Holocaust novels are something else: the exploitation of an utterly unredemptive historical catastrophe for the sake of yet another love story or coming-of-age tale or journey of self-discovery, with all the hard work of developing conflict and creating a moral universe done by the historical backdrop alone. I fault The Pawnbroker, by Edward Lewis Wallant, for unleashing over 50 years of lousy Holocaust novels on the American reading public. It accomplished this, of course, the only way it could: by being an absolute masterpiece.

Why do we read Holocaust novels? To remember, the pious secularists will intone.

But what does that mean? If it means remembering the lives of the victims, their individual and collective passions and commitments, then such novels in English have done a particularly poor job. Eighty percent of Jews murdered in the Holocaust were Yiddish speakers, for instance, yet most American readers who could name four concentration camps couldn’t name four Yiddish writers, or even identify Yiddish as a language rather than a dialect. Moreover, most of these novels—the present volume included—don’t even attempt to present any meaningful semblance of prewar European Jewish life, focusing instead on the details of its destruction. This raises a question: Why should we care how these people died, if we don’t care how these people lived?

If our sanctified remembering has nothing to do with remembering people’s lives, then the next logical assumption would be that we are meant to remember their revolting deaths—and that exposing ourselves to the degradation these people suffered will somehow sensitize us to such suffering in the future. But while required readings of Holocaust literature have hopefully primed a few generations of high school students to appreciate the depths to which humanity is capable of sinking, the premise of “never again” has unfortunately succeeded more as a rhetorical flourish than a guide to public policy. And unlike, say, the Civil War, or even the larger context of the Second World War, the Holocaust is not a human tragedy with a conceivably redemptive ending, or one where lives lost could at least be counted, however cruelly, as contributing to some worthwhile cause. In light of this, there seems to be something almost sadomasochistically prurient about the constant literary revisiting of such suffering— something that needs to be explained.

The uncomfortable truth is that Holocaust literature makes the most sense when understood not as Western but as Jewish. While secular Western culture often regards the Holocaust as somehow magically “outside of history,” the Jewish perspective is exactly the opposite: the Holocaust, while exponentially larger in scale, is part of a continuum of horrific events going back to the Hebrew Bible, and which in Jewish literary tradition are always recounted in detailed lyrical laments. The Yiddish word for the Holocaust is khurbn, a Hebrew word meaning “destruction,” used to refer to the destruction of the ancient temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE. From the origins of Jewish literature in the Hebrew Bible, and continuing through rabbinic literature’s recounting of the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and its second temple in 70 CE, and the subsequent Roman massacres after a second failed Jewish revolt in 135 CE (to mention only the destructions most fundamental to Jewish liturgy), Jewish tradition has a preexisting and religiously meaningful literary template for understanding trauma. Its vast psychological resources include not only expressions of grief and mourning, but also a necessary dose of rage and cries for justice, an awareness of a larger national immortality, and a sense of spiritual purpose for one’s own endurance in the wake of destruction.

Everyone knows the lines of Psalm 137 about those who taken as slaves after surviving the burning of Jerusalem: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat and wept as we remembered Zion… If I forget thee, Jerusalem, let my right hand wither…” But in Western culture, few continue to cite the psalm’s more graphic verses: “Daughter of Babylon, you predator: happy is he who repays what you have inflicted on us. Happy is he who seizes your babies and dashes them on the rocks!” Lines like this don’t play well in Hollywood, but they go a long way toward an honest understanding of trauma. Trauma never disappears, but its endurance is a reminder of what else can endure. The prophet Isaiah knew this, and said so, in God’s voice: “Can a woman forget her baby, or disown the child of her womb? Though she might forget, I never could forget you. See, I have engraved you on the palms of My hands.”

The Pawnbroker, modern and secular and American in every sense, bears the marks of that ancient engraving.

It is a masterpiece. Like lousy novels, masterpieces meet a set of criteria: multidimensional characters, ambiguous moral situations, and challenges to the reader’s expectations, to name a few. Of course, you could also read The Pawnbroker just for the plot. It does have one, and it will leave you in suspense. Yet its plot is not just a device to keep the reader turning pages. As the great American novelist Cynthia Ozick argues in her essay “Innovation and Redemption: What Literature Means,” plot in fiction is a deeply moral element of the work itself, the means by which the writer exposes and questions profound assumptions about how the world is or might be. “Suspense seems to make us ask, ‘What will happen to Tess next?’,” Ozick claims, “but really it emerges from the writer’s conviction of social or cosmic principle. Suspense occurs when the reader is about to learn something, not merely about the relationships between fictional characters, but about the writer’s relationship to a set of ideas, or to the universe.”

So, the plot. Sol Nazerman is a man in his forties moving comatose through life, doing the bare minimum to make it through each day. He works in Harlem as a pawnbroker—a profession that in the age of credit cards almost requires footnotes. In Sol’s pawnshop, poor people parade through the door all day carrying their most valuable possessions, hoping to use these items as collateral on high-interest cash loans. The store is a treasure house of dashed hopes, as each customer brings in something that once meant a great deal to them—a wedding ring, a musical instrument, even a trophy with the recipient’s name on it—only to see it transformed into junk. The same can be said of Sol, who, we slowly learn, has had his most treasured possessions—his home in Cracow, his career as a university professor, and ultimately his son, his daughter, and his wife—taken from him as well, in increasingly sadistic humiliations that readers will find familiar from the thousands of Holocaust books that followed this one. The reader experiences these gruesome scenes—and they are truly gruesome, at a level of nauseating realism which today’s Holocaust novels typically avoid—just as Sol does, as invasive flashbacks into an existence that Sol strives to keep as emotionally detached as possible.

Sol’s assistant in the pawnshop, an ambitious young man named Jesus Ortiz, mistakes Sol’s catatonic approach to life for calculating business acumen, especially when he notices that the store seems to be a financial success. Hoping for a foothold in the middle class, and sensing something otherworldly about his employer, he tries mightily to break through Sol’s shell. This is the part where a post-Pawnbroker Holocaust novel would have the young man succeed in uncovering Sol’s hidden humanity, in a redemptive arc ending in mentorship and hard-earned wisdom.

That’s not what happens. Instead, the pawnshop is revealed to be a money-laundering operation for a gangland empire, and it’s a matter of time before co-conspirator Sol winds up with a gun in his mouth. Things get worse from there.

Wallant was often compared in his brief lifetime with his contemporary Saul Bellow, and when it comes to his style, the comparison is apt. His Sol Nazerman feels like a Moses Herzog or a Tommy Wilhelm; the story’s naturalistic descriptions are interlaced with Sol’s own distinct cynical voice, all undergirding a larger philosophic vision: “Sol had an idea it would be quiet that day. Clairvoyance? Well, not to dignify it with scientific jargon, but there were things you anticipated with illogical confidence.

Never important things, useful things, just little moods and colors. You walked down a certain road and as you approached a farmhouse you knew there would be a smooth-skinned beech tree heavy with leaves. Things like that, never things that saved you any pain.” It must be said that the only reason Wallant is not as renowned as Bellow is that Wallant died of an aneurysm at the age of 36.

But Wallant surpasses even Bellow in creating a pantheon of empathy. Most 20th-century American writers focused exclusively on their protagonist’s point of view (and usually a protagonist similar to themselves). Yet Wallant takes on the voices and perspectives of every person who walks into Sol’s shop—not merely filtering them through Sol, but letting them speak for themselves. 21st-century readers might wince at the African-American and Latino dialects that Wallant puts in his characters’ mouths, but we also immediately sense that he knows what he’s doing. The host of minor characters is among the novel’s many triumphs. Like Sol’s, their dignity is often crushed by circumstances far beyond their control, but we see their choices in responding to those circumstances and respect them enough to judge them. Each is like a portrait by Vermeer, dark and luminous and more believable than life.

Here, for instance, is George Smith, the would-be scholar who schedules his pawnshop visits solely for the fleeting opportunity to talk philosophy with Sol, the neighborhood’s rare educated man—an intrusion Sol deeply resents. But George is no innocent victim of poverty. “George Smith had the face of an old Venetian doge,” Wallant writes, “the features drawn with a silvery-fine pencil, the excesses reproduced in the shallowest, most subtle of creases.” For another writer this would be flowery description, but for Wallant, every phrase counts—though only later do we learn why. “At one time,” Wallant explains in what seems like a throwaway line, “he had attended a Negro college in the South, but too many twistings and turnings had been engraved in him and he had been expelled from there after a discreetly hushed outrage.” Wallant builds our sympathy for George in his repeated encounters with Sol, who no longer has patience for the world of ideas or for anyone at all, and we feel George’s suffering as Sol dismisses him. It is only then that Wallant carefully and privately reveals George’s complication: he is a pedophile who fights his own predatory urges by self-medicating through books and fantasy. Our feelings about this character, brilliantly manipulated, challenge every expectation we have as readers about where our sympathies belong.

The real foil for Sol’s emotional detachment is his assistant Jesus Ortiz, a young man whose very body responds to the world exactly as Sol’s doesn’t. While Sol stands forever still, doing his best to move and be moved as little as possible, Jesus is constantly “moving with that leopard-like fluidity that made it hard to say where bone gave way to fine muscle.” He is young but far from innocent, immersed circumstantially and through his own choices in an urban underworld defined by crime. “But there had always been a deep-rooted nervousness in him,” Wallant writes, “a feeling of fragility and terror. He had never wanted to account for this feeling, because that would have been like succumbing to it.” This inexpressible inner dread, which he senses in Sol, draws him to his employer. His dream of learning a respectable business from Sol is deeply connected to Sol’s Jewishness: “Once there, in the presence of the big, inscrutable Jew, he had become even more obsessed with the magic potential of ‘business,’ for there had seemed to be some great mystery about the Pawnbroker, some secret which, if he could learn it, would enrich Jesus Ortiz immeasurably.” Jesus’s obsession with the Pawnbroker begins almost as an anti-Semitic caricature, but soon transcends it and ultimately vaults into tragedy—a true classical tragedy, with the protagonists bringing misfortune upon themselves.

In Wallant’s hands, even the caricature is rich with meaning. Sol taunts Jesus’s obsession with him (their names are hardly accidental), “explaining” to Jesus how to become a pawnbroker:

“You begin with several thousand years during which you have nothing except a great, bearded legend, nothing else. You have no land to grow food on, no land on which to hunt, not enough time in one place to have a geography or an army or a land-myth. Only you have a little brain in your head, and this bearded legend to sustain you and convince you that there is something special about you, even in your poverty. But this little brain, that is the real key. With it you obtain a small piece of cloth…You take this cloth and cut it in two and sell the two pieces for a penny more than you paid for the one. With this money, you buy a slightly larger piece of cloth…You repeat this process over and over for approximately twenty centuries. And then, voila, you have a mercantile heritage, you are known as a merchant, a man with secret resources, usurer, pawnbroker, witch, and what have you….”

“Good lesson, Sol,” Jesus said. “It’s things like that that make it all worthwhile.” All right, you are a weird bunch of people, mix a man up whether you holy or the worst devils.

The scene plays like parody, but it is much more than that—though the reader only gradually appreciates what it means. Later, in bed with his prostitute girlfriend, Jesus tells her: “Nazerman say to me one day, ‘You know how old this profession is?’… I say no, how old? And he say thousands of years. He say one time the Babylon… some crazy tribe, they use to take crops and even people for pawn. A man make loans on his family—wife, kid, anything. I mean you see what a solid business that is—thousands of years. Hard to think on thousands of years, people back then…” And thus Wallant catapults this novel out of the world of today’s uplifting Holocaust fiction and into the canon of Jewish literature and its 25 centuries of artistic responses to catastrophe.

Jesus, of course, is unknowingly invoking the biblical Book of Lamentations and its descriptions of the exiles of Jerusalem: “They have bartered their treasures for food to keep themselves alive… Behold my agony, my maidens and my youths have gone into captivity!… The precious children of Zion, once valued as gold, alas, they are accounted as earthen pots, work of a potter’s hands…” The young man has no tools to understand it, but there is a truth to the timelessness he perceives in his employer. This is a novel about not only the Holocaust, but about responses to trauma, which in Jewish history is ultimately a theological subject, one that is posed as a question rather than an answer.

The Book of Lamentations gives us as much gore as this novel does, and in fact exactly the same kind of gore: young women are raped, bodies are piled in open air, babies are eaten by their own parents, children starve, young men are worked to death as slaves. Yet it is also a book full of promises—“But this do I call to mind, therefore I have hope: The kindness of God has not ended; His mercies are not spent”—and the recurrence of this lament in Jewish history is itself a promise of an immutability beyond what any mortal can perceive. That place in the continuum of history, evoked in the subtle humanity of these many flawed characters and their inability to transcend their own histories, transforms the novel’s stunning climax into an astonishing and unexpected moment of earned redemption.

If you must, go ahead and call The Pawnbroker an American novel, a Holocaust novel—or worst of all, a novel about “the human condition.” But know that these terms will turn a treasure into cheap collateral on a short-term loan. This book is a link in a burning chain. Take hold, and feel it burn into your hands as it pulls you toward eternity.

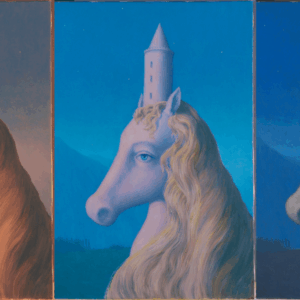

Feature image: detail from the Fig Tree Books cover of The Pawnbroker.