Frankie’s dad told him that sometimes firemen need to burn down a bad house on purpose in order to save a good neighborhood. A type of back-burn, they called it when fighting forest fires.

The father and son had been driving around in the white Fire Marshall car with the special sticker on the back window and the red light on the dashboard, except the light wasn’t switched on. They drove past spray-painted houses, houses with wood nailed over the gone windows, houses where only a basement was left, like a swimming pool filled with weeds and trees growing inside.

They drove to Frankie’s old school from before he started remote learning on the computer in their kitchen at home. After the day that Frankie’s dad called the Last Straw. After a bunch of kids dog-piled him at lunch. After they took turns stomping his head against the lunchroom floor, something Frankie couldn’t remember, even after the teachers had shown them the lunchroom video and the camera movies some kids had posted on World Star Hip Hop.

Today, same as before, his dad brought a Super Soaker, the deluxe model with the bigger tank, made to shoot longer and farther.

Firemen have a special key, his dad showed him. It opens every door. Another special key shuts off the security alarm. He told Frankie not to mind about the security videos. The high-up cameras watched them go down every hallway, walking past Frankie’s old locker, past the spot where nobody did anything besides videotape him getting his face stomped. Any trace of blood had been scrubbed away.

Same as usual, his dad worked the pump action on the Super Soaker, spraying every bulletin board hung with paper. Hosing every school spirit banner, with that service station smell. As they strolled the hallways, Frankie’s dad squirt-gunned the smell of filling the lawnmower and cleaning paintbrushes. He sprayed the ceiling tiles until they were so saturated they warped and sagged. This was his secret recipe of Styrofoam ground down to just its little white balls, dissolved in gasoline with Vaseline stirred in to make it thick, to make it sticky so when he sprayed the gunk on the ceiling it never dripped, and when he sprayed it on window glass it didn’t run down.

He’d added some paint thinner as a surfactant, his dad explained, to break the surface tension so the ooze wouldn’t bead up but would coat everything more evenly.

It was summer vacation so Frankie knew no hamsters or goldfish lived in any classroom.

His dad took aim and soaked a security camera that was spying on them.

After the day of the lunchroom beat–down Frankie couldn’t remember, his dad never looked at him. If his dad looked in his direction all he saw was the scar that now ran down the side of Frankie’s face. A red line shaped like the curved edge of a Nike basketball shoe where the cheek skin had torn. Even now walking down the empty summer hallway lined with lockers but no padlocks, Frankie could feel his dad sneak looks at the scar. Frankie’s dad never smiled at him, not after that day. He scowled, but he was scowling at the scar. The ghost of that final last stomp. The last day in public school.

Lining the halls, big posters showed smiling kids from every place on the planet. Holding hands under a rainbow with covering the rainbow the words “Love Comes in Every Color.”

His dad hosed the poster. Doing so, the look on his dad’s face was worse than any scar. From his expression, he wanted to be spraying this fire juice into the eyes and mouths of those kids who’d left their footprints on Frankie for the rest of his life.

“In his heart, Frankie knew that the bad parts of the world would have to be burned away to save the best parts.”

The whole time Frankie’s dad super-soakered the school walls, he yelled stuff like, “Eat it, cultural Marxism!” And, “Get fucked, vibrant ethnic diversity!”

His dad hosed the poster until it sagged and slid down the wet wall. By then the soaker was empty and he pitched it a long ways, almost all the way to the school office.

“In a little bit, kid,” said Frankie’s father, “I’m going to do you a solid one.”

Frankie couldn’t picture that. The kids who’d kicked his ass, they still went here. None of them had been sent home. But it helped to know that after today nobody would go here.

“Maybe they caught us off-guard once,” his dad said, “but we’ll get our revenge.”

Frankie followed his dad into a bathroom and waited while he washed his hands.

His dad said, “Nobody is going to shit on this family, ever again.” Before they went out to the car, his dad took out his phone and placed a call. He said, “Hello, may I speak to your news director?” With one hand he dug in his pants pocket. “This is Fire Marshall Benjamin Hugh. We’re currently responding to reports that the Golden Park Elementary School is ablaze.” From his pocket he withdrew a book of matches. He ended the call and placed another. “Hello, may I speak to the City Desk?” Frankie’s father held the matches out to his son. Frankie took them. Waiting, his father turned away from the phone and said, “Today is just practice. Just to see how many show up.”

Into the phone, he said, “I’ve gotten word that arsonists have struck another local school.” He listened. “It’s Golden Park Elementary.”

Frankie stood by, holding the matches, just as he’d stood by at Madison Middle School and Immaculate Heart and the three schools before. Frankie figured this would be the last school, and that his dad had only burned the others so this one wouldn’t look special. When his dad was finished with the last phone call, then Frankie knew what came next.

In his heart, Frankie knew that the bad parts of the world would have to be burned away to save the best parts.

“Frankie, you . . . ,” his dad knelt in front of him and took both of Frankie’s small hands in his own, saying, “Son, these dipshits will pay you tribute for the rest of your life!” He let fall one of the small hands and reached up to stroke the scar on the side of Frankie’s innocent, trusting face. “My boy. You will grow to become a king! And your sons will be princes!” He lifted the one small hand he still held and put it to his own lips.

As a special treat, his father let Frankie light the match.

After that they went outside to count how many reporters and cameramen would show up. At first it was only a couple television crews, but now every station came, plus some foreigners in town for the serial arson story. The newspaper sent a team. Even a helicopter. Radio stations sent people. Frankie’s dad took notes and strategized his clearest angles and best shots, to see how easy his work would be when the actual day came.

Only then did Frankie’s dad dial 9-1-1.

*

Tweed O’Neill and her crew beat the first engine company to the raging school inferno. Of course, the Fire Marshall was already on the scene. Other television news crews were soon to follow, aligning their satellite hook-ups, each angling for the best view of the blaze. It was the city’s fourth school to go up in flames recently. Every outlet worked from the same press releases, but this time Tweed had brought a secret weapon.

Enter Dr. Ramantha Steiger-DeSoto, a senior professor in Gender Studies at the university. The lady doctor was a well-spoken, camera-friendly egghead with her own unique spin on serial arson. Tweed had texted the doctor from the television studio, and the two met up at the crime scene as flames leapt high into the sky. With the gymnasium collapsing slowly behind them, sending up bright geysers of sparks and embers, Tweed blocked out the interview. She and the doctor stood at a safe distance as the cameraman adjusted his focus and the sound technician wired a microphone to the lapel of the doctor’s Ann Taylor trench coat.

Through her earpiece Tweed could hear the anchors discussing the fire. In a moment they’d throw the audience to her, live, on location. She eyed her competition. None had brought anything new to the story. They were merely passing the Fire Marshall from set-up to set-up, and he was giving each outlet the same list of official facts.

“It was the city’s fourth school to go up in flames recently. Every outlet worked from the same press releases, but this time Tweed had brought a secret weapon.”

The doctor appeared unfazed by the bright camera lights and the billowing, acrid smoke. Someone had suggested a rumored propane tank, possibly related to the school’s kiln, was liable to explode at any instant. Nevertheless Dr. Steiger-DeSoto looked determined to voice her theory about recent events. Standing tall, almost a head taller than Tweed, her frizzy blonde hair was tied up in a sensible bun. She looked every inch the no-nonsense sociologist who stood ready to enlighten the television viewers.

The cameraman shouldered his steady cam and signaled 3-2-1 with his fingers, finally pointing to indicate they’d gone live.

“Tweed O’Neill here at the scene of yet another three-alarm fire,” Tweed began. “Marking the destruction of a fourth local school this summer.”

The cameraman widened the shot to include both women. “With me tonight is Dr. Ramantha Steiger-DeSoto to present insight into the motive for these recent fires.” Tweed turned to the elegant academic. She tossed, “Your thoughts, doctor?”

The doctor wasn’t fazed by the attention. “Thank you, Tweed.” She faced the camera full-on. “Federal criminal profiling shows the average arsonist to be a white male between the ages of seventeen and twenty-six. For this man, the act of fire setting is sexual in nature . . .”

As if on cue the rumored propane tank exploded deep within the building, a concussive boom-BOOM that elicited a deep moan from the crowd present.

The doctor continued, “For the pyrophiliac, the act of spraying liquid accelerant equates to expressing his sexual ejaculate in a symbolic degrading rape of the structure . . .”

Collapsing fire and sex meant ratings gold, but Tweed worried that the doctor’s language was too highbrow. She tried to redirect. “But who . . . ?”

The doctor nodded sagely. “Self-isolating men. Right-wing adherents poisoned by the toxic masculinity of the so-called Men Going Their Own Way movement. These are your culprits.”

Tweed tried to lighten the tone. “So Maureen Dowd was right?” she joked. “That having men around is just too high a price to pay for sperm?”

The doctor smiled weakly. “For generations popular culture has been promoting the idea that all men will eventually attain high-status positions in society. Globally, today’s young males have been raised to feel entitled to power and admiration as a birthright.”

Tweed knew the station was coming up on a hard break. To cap the segment, she asked, “Doctor, how can we best deal with today’s troubled young men?”

Backed by the hellish glare of flames, the doctor proclaimed, “Men in general need to accept their diminished status in the world.” Against a backdrop of smoke and shouting, she added, “The impending war, for example, will be an excellent opportunity for them to earn the acclaim they crave.”

Tweed tossed to commercial. “Thank you, doctor. This is Tweed O’Neill at the pointless destruction of another community landmark.”

The cameraman signaled the feed had cut.

The doctor fumbled with her clip-on mic. Suddenly pensive, she asked, “What’s he doing?” She glared at something in the middle distance.

Tweed’s gaze followed hers. Both women looked at the Fire Marshall. Tweed’s impression was that he was taking a head count. His attention seemed to settle for a moment on each of the journalists present, and he seemed to be checking them off a list he held. His eyes met hers. His hand holding a pen drew a line through something on the paper held in his opposite hand.

Only now did Tweed notice the little boy. A grade school–aged child with a strange discolored mark running down one side of his face. Then the reality struck her: It was so cute. The District Fire Marshall had brought his own little son to watch Daddy at work.

Watching the two Tweed made a mental note to spin that touching father-and-son moment into a feel-good story she could peddle to network programmers.

__________________________________

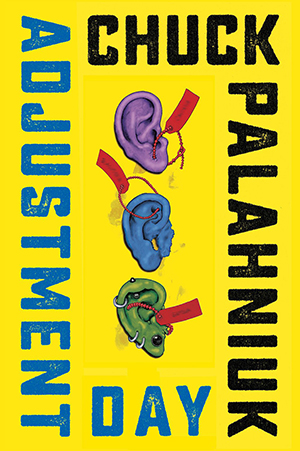

From Adjustment Day. Used with permission of W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2018 by Chuck Palahniuk.