A Brief Literary History of Robots

Beep Beep Boop Books

Isaac Asimov, one of the world’s greatest science fiction writers, died 25 years ago today. I likely don’t have to tell you this, but one of Asimov’s most enduring legacies is his creation of the Three Laws of Robotics—not to mention his host of attendant robot-related literature. So, to honor the anniversary of his death, I thought it would be fun to take a look back at some of the greatest robots in literature.

You may or may not know that robots actually originated in literature—the word was first popularized in a 1920 play by Czech playwright Karel Čapek (who was, incidentally, on Hitler’s most-wanted list). There were examples of mechanized humanoids and magically autonomous figures in literature before this play, of course, and much depends on how loose you are with your definition of “robot,” but this was the first time the word was used to describe an artificially constructed human-like tool. Happily, robots have rather caught on. In fact, some day soon they may replace their creators—writers, I mean—entirely. Below, find a few of my favorite examples of robot-related literature through the years—and since this is by necessity an incomplete list, feel free to add your own favorite robo-books in the comments.

The word “robot” was first used by Czech playwright Karel Čapek in his famous 1920 play R.U.R. (Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti). In 1923, it was adapted for the English stage as Rossum’s Universal Robots. In Czech, robotnik means “forced worker” and robota refers to “forced labor, compulsory service, drudgery”—the Online Etymology Dictionary traces it back to the Old Slavic rabu, “slave.” Of course, as science historian Howard Markel put it, “it’s really a product of Central European system of serfdom, where a tenants’ rent was paid for in forced labor or service.” But Čapek cites his brother as the real coiner of the word, writing (as translated by Norma Comrada):

It was like this: the idea for the play came to said author in a single, unguarded moment. And while it was still warm he rushed immediately to his brother Josef, the painter, who was standing before an easel and painting away at a canvas till it rustled.

“Listen, Josef,” the author began, “I think I have an idea for a play.”

“What kind,” the painter mumbled (he really did mumble, because at the moment he was holding a brush in his mouth).

The author told him as briefly as he could.

“Then write it,” the painter remarked, without taking the brush from his mouth or halting work on the canvas. The indifference was quite insulting.

“But,” the author said, “I don’t know what to call these artificial workers. I could call them Labori, but that strikes me as a bit bookish.”

“Then call them Robots,” the painter muttered, brush in mouth, and went on painting. And that’s how it was. Thus was the word Robot was born; let this acknowledge its true creator.

However, Čapek’s robots aren’t exactly what you’d imagine the first appearance of robots to be—they’re much more Westworld than Rosie the Maid. In fact, they’re made completely out of flesh and blood—though it’s synthetic flesh and blood—and have free will (but no souls)—which is what leads to their rebellion and ultimate extermination of the human race! Fun.

Asimov was a prolific writer with hundreds of books to his name, but the Three Laws of Robotics remain among his most important contributions to science fiction. According to the Handbook of Robotics, 56th Edition, 2058 A.D. (as quoted in Asimov’s 1942 short story “Runaround”), the Three Laws of Robotics are as follows:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws

Many other writers have used, amended, or flaunted Asimov’s laws, but they remain a basic principle in the Robotic canon, and in general must be either subverted or adhered to by new writers.

Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury

I assume I’m not the only one whose childhood was haunted by the Mechanical Hound of Bradbury’s 1953 classic:

The Mechanical Hound slept but did not sleep, lived but did not live in its gently humming, gently vibrating, softly illuminated kennel back in a dark corner of the firehouse. The dim light of one in the morning, the moonlight from the open sky framed through the great window, touched here and there on the brass and the copper and the steel of the faintly trembling beast. Light flickered on bits of ruby glass and on sensitive capillary hairs in the nylon-brushed nostrils of the creature that quivered gently, gently, gently, its eight legs spidered under it on rubberpadded paws.

And don’t forget the “four-inch hollow steel needle” that “plunged down from the proboscis of the Hound to inject massive jolts of morphine or procaine” into its prey. Robo-dogs are dangerous, man.

The Iron Man, Ted Hughes

World’s Worst Husband and British Poet Laureate Ted Hughes is also the creator of the Iron Man—or, as he has come to be known in America (to avoid conflation with a certain Marvel hero), the Iron Giant. He is a robot, and also an alien—when he appears in England, he causes a stir by munching on farm equipment, until he’s taken under the wing of a little boy, who teaches him to eat scrap metal and helps him defend humanity from the “Space-Bat-Angel-Dragon.” In his film iteration, he is voiced by Vin Diesel, the actor with the most robot-like name in Hollywood.

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, Philip K. Dick

Dick’s seminal work (ha ha) is still one of the most beloved works of science fiction—not to mention the basis for the film Blade Runner, in case you didn’t know. Set in 2021 (coming up fast, kids), Dick imagines a world in which almost every kind of living creature has mostly died out and been replaced with mechanized synthetic versions (Rick Deckard has a robot sheep, and actually the whole book begins because he wants the money to replace it with a live one), and though humans still exist, they’ve developed equally-convincing androids for use as servants. But sometimes those androids need to be retired… or maybe not.

The Stepford Wives, Ira Levin

When Joanna moves to Stepford, she notes that all of the women she meets look “actresses in commercials, pleased with detergents and floor wax, with cleansers, shampoos, and deodorants. Pretty actresses, big in the bosom but small in the talent, playing suburban housewives unconvincingly, too nicey-nice to be real.” Well, that’s because they aren’t… 45-year-old spoiler alert: the wives are robots. The same kind, more or less, that they have at Disneyland, thanks to one animatronics-designer husband. The actual wives were killed and replaced—or perhaps the more appropriate term is upgraded.

The Cyberiad, Stanislaw Lem

Two of the best characters in literature have to be Trurl and Klapaucius, best friends and rival inventors who also happen to be hyper-intelligent “constructor” robots who can make pretty much anything. They live in a strange world that is essentially an epic fantasy land (read: broadswords) and sometimes, being chaotic good machines, use their powers to help others. I love Lem, and this collection of stories is his masterpiece.

Cyborg, Martin Caidin

This 1972 novel isn’t particularly important for its literary quality, but is legendary for what it spawned: The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman. Cyborgs, of course, are somewhat different from true robots, being part man and part machine, but in this instance, I’m calling it close enough.

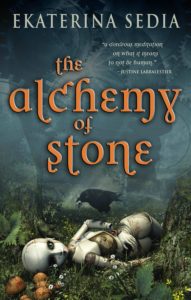

The Alchemy of Stone, Ekaterina Sedia

The protagonist of this crazy steampunk fantasy novel is a sentient clockwork automaton whose owners set her free—but kept the key that winds her heart. She (“she” because of the way she was made, with built-in petticoat) gets caught in an elaborate war—an industrial revolution of sorts that pits three factions against each other. This is a good example of the ways robotics have infiltrated other genres than strait science fiction—The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi is another good one.

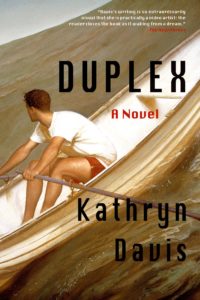

Kathryn Davis, Duplex

One of my favorite recent examples of robots cropping up in literary fiction is in Kathryn Davis’s Duplex, which begins with a woman walking down a suburban street: “She was a real woman; you could tell by the way she didn’t have to move her head from side to side to take in sound.” At first this seems odd, or perhaps somewhat sexist, like the 1950s—but eventually you realize what the narrator means: she’s not a robot. Or, you know, a sorcerer. Both live in the neighborhood, after all. The normal and the fantastic are roommates in the duplex. Now I’m going to go ahead and quote too much, because I love this book:

Everyone knew the family inside number 37 were robots. Mr. XA, Mrs. XA, Cindy XA, Carol XA—when you saw them outside the house they looked like people. Carol had been in Miss Vicks’s class the previous year and she had been an excellent if uninspired student; Cindy would be in her class starting tomorrow. The question of how to teach—or when whether to teach—a robot came up from time to time among the teachers. No one had a good answer.

…

It was only when everyone on the street was asleep that the robots came flying out of number 37. There were four of them, two the size and shape of needles and two like coins, their exterior surface burnished to such a high state of reflective brilliance that all a human being had to do was look at one of them for a split second to be forever blinded. The robots waited to come out until after the humans were asleep. They’d learned to care about us because they found us touchingly helpless, due in large part to the fact that we could die. Unlike toasters or vacuum cleaners, though, the robots were endowed with minds. In this way they were distant relatives of Body-without-Soul, but the enmity between the sorcerer and the robots ran deep.

You’re welcome.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.