20 Books That Deserved More Attention in 2017

Freeman's Contributors on their Favorite Undersung Titles

With a hateful and erratic would-be tyrant consuming all the oxygen in the room, 2017 was a year in which we especially needed books, while books themselves had less air than ever to breathe. I asked some recent contributors to Freeman’s what they wished had received more attention in 2017. Here are their answers.

Elif Shafak, Three Daughters of Eve

After a thief tries to steal her handbag in downtown Istanbul, Peri looks back at her time in Oxford University and her fascination with the unorthodox lecturer who taught a seminar on God. Intellectually satisfying, eye-opening and full of quotes from T.S Elliot to Hafiz that are worth pursuing.

—Leila Aboulela, author of The Kindness of Enemies

Nicole Sealey, Ordinary Beast

Almost all poetry books are overlooked, so allow me to pick one, a great one that came out in 2017: Nicole Sealey’s Ordinary Beast, which is fresh, powerful and poignant. I could have gone with Danez Smith’s Don’t Call Us Dead, or Kaveh Akbar’s Calling a Wolf a Wolf, or Morgan Parker’s There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé, but you only asked for one.

—Rabih Alameddine, author of The Angel of History

Chris Ware, Monograph

Chris Ware’s graphic memoir, Monograph (Rizolli), at almost nine pounds and the size of a small child, is hard to overlook—yet it was. The book, built of Ware’s illustrations, sheet music, family photos, sculptures, inventions, writings, mini books, and more, shows a mind of extreme elasticity and invention and an understanding that the architecture of memory is cumulative and complex.

—Kerri Arsenault, author of “Vacationland“

Camille T. Dungy, Guidebook to Relative Strangers

Part memoir, part travelogue, part parental guide, this book is a stunningly beautiful love letter from a mother to her daughter to help her daughter embrace the world she lives in, to introduce her to her ancestors, and prepare her for the future.

—Edwidge Danticat, author of The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story

Sarah Hall, Madame Zero

I don’t think it was overlooked—from here I don’t really notice what happens in the American market—but Madame Zero by Sarah Hall is brilliant and I haven’t heard the raving it deserves.

—Mariana Enriquez, author of Things We Lost in the Fire

Alexis Okeowo, A Moonless, Starless Sky

I wouldn’t say this book was completely overlooked, but I wish more people were talking about A Moonless, Starless Sky: Ordinary Women and Men Fighting Extremism in Africa by Alexis Okeowo. It sheds light on the everyday ingenuity, bravery and resilience of people throughout the continent taking a stand against oppressive forces in ways both big and small. Okeowo, a Nigerian-American, is as gifted a storyteller as she is a reporter. I’ve pushed her book into many a friend’s hand this year.

—Angela Flournoy, author of The Turner House

Joca Reiners Terron, Noite dentro da noite

Noite dentro da noite (Night inside/within night), by Joca Reiners Terron, is one of the more astounding novels published in Brazil in recent years, a feat of crafting virtuosity where a family saga and the horrors of history and nature are ingredients for an a hallucinatory tale about the powers of imagination.

—Daniel Galera, author of The Shape of Bones

Claude McKay, Amiable With Big Teeth

McKay is the first great modernist of the English-speaking Caribbean and the discovery of this unpublished novel in 2009 highlights a new dimension of his unceasing examination of black lives against and within the stream of social and political unrest.

—Ishion Hutchinson, author of House of Lords and Commons

A long-lost book from one of the Harlem Renaissance’s most important writers, it looks at the African-American response to 1930s fascism.

—Nadifa Mohamed, author of The Orchard of Lost Souls

Amiable with Big Teeth was covered briefly during black history month when it came out, and then people stopped talking about it. Harlem Renaissance author Claude McKay wrote this novel about social movements decades ago but it was only published this year. (It took a while to verify that it was realy written by McKay.) The book takes place in the mid-1930s and explores conflicting ideologies between communists and black nationalists.

—Emily Raboteau, author of Searching for Zion

Jennifer Chang, Some Say the Lark

This year, I found comfort in Jennifer Chang’s Some Say the Lark, a collection of poems bursting with wonder and intelligence and rage. I especially enjoyed the rage.

—Tania James, author of The Tusk that Did the Damage

Walter Kempowski, All for Nothing, tr. Anthea Bell

My overlooked author of 2017—overlooked at least beyond Germany—the late Walter Kempowski. All For Nothing, translated into English only recently, is a beautiful, insanely moving depiction of the atrocities of war, mostly seen through the eyes of a child. Kempowski’s elegant, languid prose becomes savagely ironic, as the horrors unfold. In stark contrast, another work of Kempowski’s, Dog Days, is a tragicomic study of the novelist, in all his self-lacerating solitude, vanity and passion.

—Joanna Kavenna, author of A Field Guide to Reality

Paul Yoon, The Mountain

This haunting and expansive story collection will carry you through time and across borders, and will stay with you for a long time. Yoon is a beautiful writer, whose silences speak as powerfully as his words.

—Claire Messud, author of The Burning Girl

Camilla Grudova, The Doll’s Alphabet

This book includes much discussion of the sexuality of sewing machines. Which, I dare say, is my cup of tea.

—Heather O’Neill, author of The Lonely Hearts Hotel

Karolina Ramqvist, The White City, tr. Saskia Vogel

The White City, by the Swedish novelist Karolina Ramqvist. Pure tension, the kind of tension I love: intimate, exquisite and ruthless.

—Samanta Schweblin, author of Fever Dream

Diksha Basu, The Windfall

The serious comic novel is a rare beast, and too often misidentified as something frothy (particularly when written by a woman). So, while this debut novel received plenty of praise for its humour and charm, not enough attention was paid to its astuteness about class, money and gender in 21st century India.

—Kamila Shamsie, author of Home Fire

Jenny Erpenbeck, Go, Went, Gone, tr. Susan Bernofsky

Jenny Erpenbeck’s Go, Went, Gone (a title catchier in the original, “Gehen, Ging, Gegangan”) is a deeply thoughtful and involving novel about migrancy now. Retired ex-GDR Classics professor Richard, himself unhoused by war in infancy, befriends a group of African refugees in Berlin: grippingly interrogatory fiction.

—Helen Simpson, author of Cockfosters: Stories

Alicia Suskin Ostriker, Waiting for the Light

I loved Alicia Suskin Ostriker’s Waiting for the Light, an unblinking tour through the various urgencies of city life that swells into a gorgeous and restorative treatise on love and compassion.

—Tracy K Smith, author of Ordinary Light

Juan Villoro, The Reef, tr. Yvette Siegert

I adored Yvette Siegert’s translation of Juan Villoro’s The Reef, published by George Braziller this summer. I find The Reef, like all the best books, nearly impossible to summarize, but it is a daring madcap heartbreak, the kind of book that’ll keep you pinned to your chair, the kind of book I want to push into the hands of just about everyone I meet.

—Laura van den Berg, author of Find Me

Frederika Amalia Finkelstein, Survivre

Survivre by Frederika Amalia Finkelstein, about the Bataclan attack and what a young parisian girl (born in Argentina) feels about it. Obsessed by the photo of the dead in the orchestra pit of the Bataclan she circles around the obsession and draws an impressive portrait of France and youth today. It ends in Patagonia, with a strange and perfect logic.

I love this book and almost nobody talked about it, while her first novel was very well received. It’s the “second novel syndrome,” and I have sympathy for it. I’m sure she’ll be a great writer, if she survives this world. She’s very young.

—Marie Darrieussecq, author of Being Here, the Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker

Edwidge Danticat, The Art of Death

Death, that unwelcome equalizer and merciless lawnmower, leaves us dumbfounded or sputtering cliches in its wake, so Edwidge Danticat’s moving little gem, The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story—a meditation on grief and death and the ways we try to give expression to the inexpressible—was one of the books this year I found essential, especially for those scrambling to find words and meaning when the clocks have stopped.

—Garnette Cadogan, author of “Black and Blue”

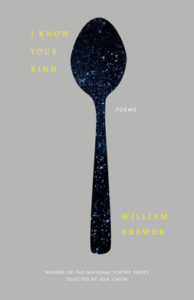

William Brewer, I Know Your Kind

These poems examine, interrogate, and tend to questions of rural selfhood, the opioid epidemic and the political in a vernacular that unflinchingly grafts itself from our American moment. While other projects examine addiction through a singular and limited self, Brewer’s collection is a prime example for what can be accomplished when a poetical praxis is used to implement large and tricky-to-wield questions, particularly by moving outward to thoroughly probe an epidemic as it effects a state, a region, a people—as well as the individual. It holds our gazes to the underbelly and shows us that, here, too, the imagination thrives and, like all undeniable art, is written in spite of all the things that work to silence it.

—Ocean Vuong, author of Night Sky with Exit Wounds

John Freeman

John Freeman is the editor of Freeman’s, a literary annual of new writing, and executive editor of Literary Hub. His books include How to Read a Novelist and Dictionary of the Undoing, as well as a trilogy of anthologies about inequality, including Tales of Two Americas, about inequity in the US at large, and Tales of Two Planets, which features storytellers from around the globe on the climate crisis. Maps, his debut collection of poems, was published in 2017, followed by The Park in 2020. His work has been translated into more than twenty languages and has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The New York Times. He is the former editor of Granta and teaches writing at NYU.