16 Books You Should Read This November

What to Read As the Nights Grow Dark

Swing Time, Zadie Smith

(Penguin Press)

I cannot wait to re-enter Zadie Smith’s world of frenetic words and perfect sentences, the energetic ride you take the second you start reading her. Smith’s hectic, hilarious, tragic city of millions of unique and diverse characters is exactly the London I love. In Swing Time, her fifth novel, the story moves from North-West London to West Africa, and centers on the friendship of two brown girls who dream of being dancers. The day a new Zadie Smith book comes out should be a national holiday. Finally!

–Marta Bausells (Lit Hub editor-at-large)

Sing the Song, Meredith Alling

(Future Tense Books)

An ancient ham rolls out from a sewer to tell fortunes. A mother outsmarts a masked criminal. A small man crawls out from behind a TV. These are the nerve-tugging, dreamlike stories within Meredith Alling’s Sing the Song, a short story collection fueled by a daring psychology that magnifies the mysteries and anxieties of our everyday world while revealing the surrealism of modern life. For fans of writers like Diane Williams, Amy Hempel, Lydia Davis, Ben Marcus, and Amelia Gray, Alling will be welcomed as a voice necessary to the fabric of fiction.

–Bianca Flores (Lit Hub editorial intern)

In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Christina Sharpe

(Duke University Press)

Drawing upon numerous interpretations of the word “wake,” Tufts University professor of English Christina Sharpe examines cultural representations of blackness in American history, from the slave ships and the malignant history they left in their wake, to funereal imagery (like a wake), to a sudden awareness of such continued and pervasive injustice (being “woke”). Such studies perform a vital correction to the historical and literary narrative of America, they give important insights into the state of contemporary society, and they look hopefully (if a little wearily) to the future, and the hope that later generations will know and do more. In the Wake is a necessary chapter in a lengthy tome of ending white supremacy.

–Jonathan Russell Clark (Lit Hub staff writer)

Frantumaglia, Elena Ferrante

(Europa Editions)

I developed Ferrante Fever relatively late. You have to read these books, the Internet kept saying, but for a long time I didn’t read them. Those books with the little girls on the covers that look like Hallmark cards? I said, Sure, I’ll get around to it. I wondered if perhaps the hype stemmed largely from Ferrante’s refusal to promote herself in an age of gluttonous self-promotion. Then I read them. It did not. For me, her books surpassed expectation, coming across less like Jane Austen, to whom she has been compared, and more like Austen’s angrier, more insightful sister—telling it like it is while drunk on fables and feminism. Her plainspoken storytelling not only propels you forwards through many hundreds of pages, but shocks you with a kind of private recognition that, in its freshness, feels revelatory. This month, Europa gives fans two new books by the author that lie on opposite ends of the Ferrante spectrum: Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey presents fragments of Ferrante’s (still pseudonymous) real-life letters and personal writings, while The Beach at Night—a “children’s book” that is most definitely not for children, about a forgotten doll—is a fever dream of a fairy tale in the old tradition, where inanimate objects possess feelings and desires in a world thrumming with danger and quotidian violence.

–Summer Brennan (Lit Hub contributor)

Moonglow, Michael Chabon

(Harper)

With charm and wit, Michael Chabon usually writes about dreamers, creators, and adventurers living in a fascinating, messy world. Since he does it with playfulness—I love how he conjures worlds from a mashup of genres—and with language that sparkles with winsome intelligence and demonstrates an eye for big topics and fine detail, I am always on impatient lookout when I hear he has something new coming out. His novel Moonglow, “an autobiography wrapped in a novel disguised as a memoir,” which moves from a love between grandparents to an account of the “American Century,” will surely be a book I’ll get lost in as soon as it’s out in late November.

–Garnette Cadogan (Lit Hub contributing editor)

The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz, Johann Valentin Andreas

(Small Beer Press)

Proclaimed by John Crowley, the editor of this deluxe illustrated 400th anniversary edition, as the first sci-fi novel, The Chemical Wedding of Christian Rosencreutz is an outlandish novel that includes some of the most bizarre and remarkable imagery I’ve read in a long time. Possibly allegorical and definitely Kafkaesque (if anachronistically so), this edition of an obscure classic is just thing for November 2016.

–Stephen Sparks (Lit Hub contributing editor)

Invisible Planets, Ken Liu

(Tor Books)

Ken Liu is known best for his Dandelion Dynasty fantasy series. But he’s also an award-winning translator. This month, his riveting English translation of thirteen Chinese science-fiction stories, Invisible Planets, hits shelves. It’s the first collection of its kind, each story brimming with imaginative landscapes and thought-provoking futures that pull from both Western and Chinese literary canons. Three critical essays at the back of the book discuss the importance of science fiction in Chinese culture, making this a vital anthology for fans of sci-fi and literature in translation.

–Amy Brady (Lit Hub contributor)

The Fate of the Tearling, Erika Johansen

(Harper)

The Fate of the Tearling is the final entry in Erika Johansen’s clever and surprising trilogy. The books thus far have been an addictive examination of both the dangers and the limits of political power, and more surprises are in store for Queen Kelsea. Such a satisfying end to a potent blend of fantasy, literary fiction, time travel, and feminism. I can’t wait to dissect it with fellow fans.

–Stephanie Anderson (Lit Hub contributing editor)

The Great American Songbook, Sam Allingham

(A Strange Object)

In The Great American Songbook, the genuinely unsettling bumps up the straightforwardly poignant; despite featuring not insignificant bloodshed, it’s no coincidence that fully half the blurbs on its back cover invoke the word “tender.” Even as the stories unfold with the logic of dreams, the characters within them are always recognizably human—whether grieving daughters, cello-playing bourgeois assassins, or even literal animals, like the hard-drinking existential duck of “Bar Joke, Arizona.” A personal plus: the book also functions as a thumbnail sketch of sorts of Philadelphia and its surrounding areas, which can feel like a rare treat in contemporary fiction (Franzen’s “mixed grill” notwithstanding.)

–Jess Bergman (Lit Hub assistant editor)

Thus Bad Begins, Javier Marías

(Knopf)

A new book from Javier Marías is always cause for celebration. The author of modern masterpieces like A Heart So White and Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me commands as much excitement (not to mention reverence) as any writer alive. His newest, Thus Bad Begins, burrows deep into a troubled marriage. It’s a heady mix of suspicions and secrets. Marias’ set pieces are a marvel—a wife paces in front of a bedroom door, smoking a cigarette, pulling at her nightgown; an angry husband refuses to let her inside. From a gesture here, a word there, Marias spins an entire world.

–Dwyer Murphy (Lit Hub contributing editor)

The Emigrants | The Rings of Saturn | Vertigo, W.G. Sebald (trans. Michael Hulse)

(New Directions)

And so they are ever returning to us, the dead. The closing words of The Emigrants are the perfect distillation of W.G. Sebald’s novelistic project, a masterful blending of memoir, fiction, and history in the crucible of an elegant, elliptical prose style. These gorgeous new editions from New Directions (complete with immaculate Peter Mendelsund covers) are a perfect reason to revisit the haunting Sebaldian voice, an astonishing liturgist of the shared melancholy of history.

–Dustin Illingworth (Lit Hub staff writer)

The Dispossessed, Szilard Borbely (trans. Ottilie Mulzet)

Szilárd Borbély’s peasants run alongside the everymen and -women of László Krasznahorkai, his landscapes are the dusty, spare worlds of Béla Tarr. Although acclaimed as one of Hungary’s major poets and essayists of the post-Communist era, he is little known in the West, where his publications have been few. The Dispossessed, his only novel, and the last work he completed before his tragic 2014 suicide, is a major work that should come to stand alongside Hungary’s melancholy literary riches. Expertly translated by Ottilie Mulzet, who has done numerous works by Krasznahorkai, it must be read. Plus, do not miss Borbély’s Berlin-Hamlet (also translated by Mulzet), also out this month from NYRB Poets.

–Scott Esposito (Lit Hub contributor)

Bob Dylan, The Lyrics: 1961-2012

(Simon & Schuster)

Putting the Nobel hoopla aside, I really can’t wait to have Bob Dylan: The Lyrics 1961-2012 in my hot little hands. If you are a regular reader of this space you know I have great admiration for the man and his art, but I’m curious about how his words will look on the page. Will the songs with endless, clever rhymes feel like poetry? The story songs leave me satisfied? I can’t wait to find out.

–Lisa Levy (Lit Hub contributing editor)

Writing to Save a Life, John Edgar Wideman

(Simon & Schuster)

A 14-year old Chicago boy was murdered because a southern white man thought that the boy might have winked at the man’s wife. Emmett Till’s only crime was being black in 1955 in Mississippi, where he was visiting relatives from his hometown of Chicago. His murder galvanized a nation when his mother, Mamie Till, insisted on an open coffin so that a nation could bear witness to the violence that had been done to her son. Emmett was not the first Till man whom Mamie had had cause to say a premature goodbye to: a decade prior, Louis Till—Emmett’s father—had been court-martialed and hanged for the rape and murder of an Italian civilian at the end of World War II. In Writing to Save a Life, John Edgar Wideman returns to creative nonfiction after a 15-year absence in order to explore what happened in Italy in the summer of 1945. But this is not just some micro-history of a single case of injustice. In Wideman’s hands, it is a story about “the American darkness that disconnects colored fathers from sons, a darkness in which sons and fathers lose track of one another.” In a writing career that is already full of tremendous achievements, this slim volume represents some of Wideman’s most powerful work.

–Lorraine Berry (Lit Hub contributing editor)

Searching for John Hughes, Jason Diamond

(William Morrow)

I’ve run a literary website with Jason Diamond for a number of years now, and so I’ve been eagerly anticipating his first book ever since I heard that it was in the works. Searching For John Hughes is a moving book about frustration, creativity, and defining yourself—and it’s also a tremendous primer in how the idea of doing something can sometimes overtake the actual doing of it. And there’s a Rites of Spring epigraph, which never hurts.

–Tobias Carroll (Lit Hub contributor)

The Selected Short Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin, Ursula K. Le Guin

(Simon & Schuster)

The only thing better than Ursula K. Le Guin is more Ursula K. Le Guin. To that end, we all probably need this very attractive box set, which collects some 1,500 pages of the legendary writer’s shorter works, spanning four decades and countless genres. The two volumes inside—The Unreal and the Real, which contains a selection of stories chosen by the Grand Master herself, and The Found and the Lost, a collection of her novellas—are already available as standalone hardcovers, but, well, there’s just something so irresistible about a nice matched set. Particularly when the insides are this brilliant.

–Emily Temple (Lit Hub associate editor)

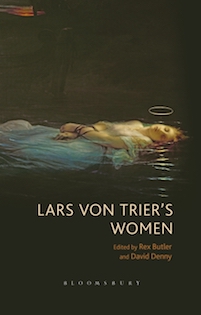

Lars Von Trier’s Women, ed. Rex Butler & David Denny

(Bloomsbury Academic)

Love him or hate him, there’s no denying that Lars Von Trier is one of the boldest filmmakers working today. Unsurprisingly, he’s also one of the most controversial contemporary filmmakers as well. One of the biggest controversial topics surrounding his oeuvre is his relationship with women, with feminism, with sexism, with misogyny. His female characters are certainly complex—whether we’re talking about Grace from Dogville, Justine from Melancholia, Bess from Breaking the Waves, Selma from Dancer in the Dark, Joe from Nymphomaniac, or She from Antichrist—but he has been criticized for subjecting these characters to extreme violence and humiliation, sometimes with a seemingly sadistic cinematic glee. Rex Butler and David Denny have put together a collection of essays on Lars Von Trier’s films that speak solely to this complicated (some might say “problematic,” though I hate that word) aspect of his work. These essays sometimes harmonize with, and sometimes conflict with, one another in their assessment of Von Trier. The editors don’t force a particular reading of his relationship with women. Instead, the pieces allow you to dwell in the weird worlds Von Trier creates and contemplate what to make of his predilections and provocations and politics. If you’re a contemporary cinema aficionado—and in particular if you’re interested in the work of Lars Von Trier—this collection of in-depth film analyses is worth checking out.

–Tyler Malone (Lit Hub contributing editor)