15 Books to Read This May

Scaachi Koul, Jillian Tamaki, Amelia Gray, and More

Kirsten Bakis, Lives of the Monster Dogs

For years, Kristen Bakis’s Lives of the Monster Dogs has occupied space in my brain. First, there’s that title–hard to shake even before I’d read the novel. Then there’s the story itself, an evocative and metaphorically rich story of an isolated society of sentient dogs that take up residence in New York, and the rival factions and tragedies that bedevil them. (Oh yeah: this is also a great New York novel.) I’m excited to see it back in print; an introduction by Jeff VanderMeer for this edition sweetens things even more.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

Scaachi Koul, One Day We’ll All Be Dead and None of This Will Matter

The title signals what’s ahead: trenchant wit intertwined with poignancy, deftly transmitted at multivalent frequencies. The humor and hurt in Sccachi Koul’s essays lands with an irresistible amplitude that arrests you and releases you in hysterical laughter. Time with them is time given over to a rib-rattling-funny mix of sharp observations and insightful reflections on the absurdities, anxieties, and frustrations of our hyper-connected (yet too-often-alienating) contemporary world. She navigates this world as the daughter of immigrants, and is therefore at once too visible and too invisible; we often see her, then, trying to find her footing while standing her ground. So, of course, I look forward to encountering her sharp eye and hilarious side-eye in this debut collection of essays.

–Garnette Cadogan, Lit Hub contributing editor

Charmaine Craig, Miss Burma

Based on the author’s own family history, Miss Burma by Charmaine Craig (The Good Men) tells the story of two generations struggling with love, war, and imperialism. In Rangoon, Benny meets and falls in love with Khin, who’s part of an ethnic minority group called the Karen. When World War II brings the Japanese Occupation, the couple is forced into hiding. Years later, their daughter, Louisa, finds fame as Burma’s first beauty queen. Soon a dictator rises to power, and Louisa is torn between her loyalty to her mother’s people and the governmental powers that be. It’s a gorgeously-written novel that illuminates the universalities of fear and the desires for dignity and freedom.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

Andrew Schelling, Tracks Along the Left Coast: Jaime de Angulo & the Pacific Coast

Schelling’s biography of Jaime de Angulo—”cattle puncher, medical doctor, bohemian, buckeroo,” among other things—presents a fascinating, full-bodied portrait of a man and an era, as well as delving deep into California’s Native history. De Angulo’s isn’t a household name, but in Schelling’s work the man called by Ezra Pound the “American Ovid” comes blazing to life in all his singular brilliance.

–Stephen Sparks, Lit Hub contributing editor

Jana Beňová, Seeing People Off, tr. Janet Livingstone

Seeing People Off is a 120-page comedy about a quartet of creative types in Bratislava, Slovakia. The vignettes throughout the book are rarely longer than a page and are sometimes as short as a single line, and they convey the angst and indolence of creative life. The characters are typically on the edge of being broke, but live indulgently and shortsightedly each time they come into some money. This book will make you laugh. There’s very little literature from Slovakia in English (and it’s Two Dollar Radio’s first translation), so it’s special for that reason, too.

–Nathan Scott McNamara, Lit Hub contributor

Jillian Tamaki, Boundless

This is Jillian Tamaki’s first collection of short stories, and it’s a truly gorgeous object. Each story is drawn or inked in a completely different style, making it feel like many precious graphic novels in one. They all look at the lives of contemporary women and the weight of expectations on their virtual and IRL selves. You might already know Tamaki for her award-winning This One Summer or Supermutant Magic Academy. If not, this is an exciting chance to get to know her mix of perceptive humour, realism and fantasy. It is as good as Adrian Tomine (who said she “seems capable of drawing anything, in any style, and making it appear effortless”) but also feels completely new.

–Marta Bausells, Lit Hub contributing editor

Kei Miller, Augustown

The Jamaican writer Kei Miller—poet, novelist, essayist, short story writer—knows few boundaries when it comes to literary genres. His poems traverse almost all terrain, from short prose poems like “The Law Concerning Mermaids” to sprawling, architecturally inventive texts like “The Shrug of Jah” in The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion, the words of which zigzag across the white space and echo the experiments of Kamau Brathwaite. His perhaps-best-known novel, The Last Warner Woman, is often as lyrical as his poetry, and his essays often blend ribald, schoolyard humor with socio-political and literary critique. Miller’s latest novel, Augustown (Pantheon), charts similarly blended territory, turning the real-life Jamaican August Town into a fictionalized world named Augustown in the 1980s. The area is located in “a dismal little valley in a dismal island,” beyond the glitz of tourist brochures, yet in it we find characters bursting with beautiful life—surrounded by darkness, but far from dismal. Miller has historically been a little uneven, but he is a brilliant, beautiful writer when in his element—one of the Caribbean’s best. Early on, Augustown‘s narrator remarks that “every day contains all of history.” The phrase, echoing time in works by Woolf, Joyce, and Garcia Marquez, says so much so compactly, and this is Miller’s gift.

–Gabrielle Bellot, Lit Hub staff writer

Qiu Miaojin, Notes of a Crocodile, tr. Bonnie Huie

In the fall of 2015, I read Qiu Miaojin’s Last Words from Montmartre, and I’ve been waiting ever since to get my hands on the English translation of her one and only other book, Notes of a Crocodile. Sadly, Qiu only wrote two books because she killed herself shortly after finishing Last Words from Montmartre at the young age of 26. Upon Crocodile‘s release in 1995, it quickly became a cult classic of queer literature in her native Taiwan, and it won Qiu a devoted following that is still ardent to this day. Given all the debates we’re just beginning to have about gender and sexuality, Qiu was clearly ahead of her time, and even if it took 20 years to reach us, I think Notes on a Crocodile will have a big impact.

–Scott Esposito, Lit Hub Columnist

Minae Mizumura, Inheritance from Mother, tr. Juliet Winters Carpenter

Minae Mizumura’s Inheritance from Mother (Other Press) slices through the stereotype of the selfless Japanese mother, while also showing the tightrope modern middle-aged women balance on in Japan. Mitsuki Katsura is 50-something, an academic, and married to another academic. After she writes “Today my mother died,” her entire world will be altered, and so will the reader’s—this isn’t your expected lit-fic meditation on childhood, but a thrilling take on the old-fashioned serial, 66 short chapters that will keep you riveted yet leave you sad, exhilarated, thinking.

–Bethanne Patrick, Lit Hub contributing editor

Mary V. Dearborn, Ernest Hemingway: A Biography

Mary V. Dearborn has written stellar biographies of Norman Mailer, Peggy Guggenheim, and Henry Miller. Now she’s set her sights on perhaps her most difficult subject yet: Ernest Hemingway. Difficult because it would be hard for anyone to compete with the tidal wave of words already written about him. Yet Dearborn offers a unique perspective, and only partially because she’s the first woman to ever write a full biography of Hemingway. She also uncovers plenty of fresh material and exposes new sides of the iconic author to the light. Her greatest strength lies in her ability to avoid the most perilous pitfall of writing about Hemingway: either romanticizing the machismo or flatly condemning it without a deeper engagement with it. Instead, she explores it honestly and with grace. Someone with this depth of knowledge and lightness of touch was needed to fully grapple with all the complexities of this haunted and haunting American master. This is now required reading for anyone with more than a passing interest in “Papa.”

–Tyler Malone, Lit Hub contributor

Aja Monet, My Mother Was a Freedom Fighter

Aja Monet’s writing blazes. We read her becoming in these poems: inchoate smart black feminist revolutionary to full-blown erudite wild woman change-maker. In “the young” she writes: “in our youth / we listen to the world laugh / at the sport of us dying.” In “we are (inspired by Mahmoud Darwish),” “i have faced worse things than being forgotten” and . . . “we take to the streets as a sort of rain / descending atop roofs of all those who make / laws to define the absence between us.” Haymarket Books is the ideal publisher for these breathtakingly fierce poems. In the poem “sentiments of the colored women” she writes, “feeling our way through / the right to rise luminous.” Monet more than rises; she stays aloft.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub columnist

Amelia Gray, Isadora

I have long been a fan of Amelia Gray’s work—her short stories are like little surgeries: brutal and transformative. Unlike (most) surgeries, they are also often funny. Her first novel, Threats, read like an extension of one of these, but her second novel, Isadora, transcends everything else she’s ever done. Everything I love is still in there—the weird, the witty, the body-strangeness—but in this imagining of the life of Isadora Duncan after the death of her two children, Gray’s work has reached new heights of complexity and emotional depth. In case you aren’t convinced, the book includes this sentence: “Damned forever, she felt herself relax.” Relatable!

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub associate editor

Tomas Tranströmer, The Half-Finished Heaven: Selected Poems, tr. Robert Bly

In 1962, Robert Bly had a lot of energy. Once, on a hunch, he drove seven hours to pick up a copy of a book in Swedish by Tomas Tranströmer at the University of Minnesota. Ever since that cannonball run, Bly has been one of the Nobel laureate’s most ardent translators, supporters, and interpreters. He published his own translations in his annual-ish journal the 60s, and again when it changed its name to the 70s and the 80s. For years Bly and Tranströmer also conducted a correspondence on love, poetry, family, war, the poetry business, and their respective countries. It was collected in a book called Air Mail which is one of the only books of letters that is also so clearly a story of a friendship. I would say every poet should read it, but actually anyone who knows the mercurial and also undignified life of the arts, and how it occasionally gives you friendships from afar, should. Tranströmer died in 2015, just a few years after he’d finally won the Nobel he so richly deserved, and Bly is with us yet. In this new updated version of his selected poems we find more than a dozen new translations from Tranströmer’s strange and blue-ish work. To read these versions in 2017 is like seeing the after-image of a great work. They are eerie and beautiful and a little bit sad, like so much of Tranströmer’s poetry. Heaven it seems will always be half-finished.

–John Freeman, Lit Hub executive editor

Patricia Lockwood, Priestdaddy

The hilariously profane verbal contortions of Patricia Lockwood are well-known to anyone who’s ever had a passing interest in “Weird Twitter”—or who read her 2013 poem “Rape Joke” which, full of startling, expertly framed detail, remains “the most viral poem of all time.” In Priestdaddy—so-named for her capital-F Father, ordained as a priest through a special dispensation from the Vatican—she sustains the singular tone for which she is known over more than 300 pages without, it seems, breaking a sweat. The result is a marvel, a Frankensteining of wit, depravity, and tenderness that shouldn’t work but nearly always does. When asked by her mother at one point how to write a poem, she replies that “you start by thinking sideways,” and Priestdaddy gives us the pleasure of encountering the world through this diagonal vision. Though Lockwood more or less left the religiosity of her upbringing behind at the age of 19, it’s clear that, in the writing, she’s found another form of grace.

–Jess Bergman, Lit Hub features editor

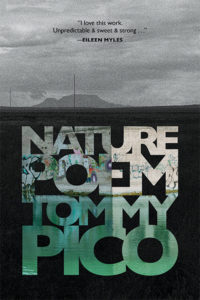

Tommy Pico, Nature Poem

There are so many different textures in the poetry of Tommy “Teebs” Pico, an American Indian (or NDN) queer poet. Pico combines the hashtags of Tweets with the patient adjectives of odes to give us a language that pushes the boundaries of poetry. “I can’t write a nature poem,” says Pico, but I am certain that he found a way. Nature Poem is out May 9th from Tin House and I cannot wait to get my hands on a copy.

–Laura Buccieri, Lit Hub editorial fellow