16 Books to Read This April

Julie Buntin, Sarah Gerard, Norman Podhoretz, and More

Sarah Gerard, Sunshine State

(Harper Perennial)

Sarah Gerard’s debut novel Binary Star was a haunting portrait of the physical and societal disconnection felt by its narrator; her chapbooks Things I Told My Mother and BFF brought a similar prose intensity to nonfiction; and her ongoing series of essays for Hazlitt are frequently harrowing in their juxtaposition of her past and present. So Sunshine State, her first collection of essays, is pretty much the definition of “highly anticipated” for me.

–Tobias Carroll, Lit Hub contributor

David Haskell, The Songs of Trees

(Viking)

David Haskell’s The Songs of Trees, a follow up to his Pulitzer Prize nominated Forest Unseen, is a consciousness expanding inquiry into forest ecosystems. Lyrically weaving his way across the globe, Haskell provides his readers with a lively arboreal tour that focuses on the relations that constitute some of our richest and most threatened ecosystems, revealing along the way the connections fostered by trees.

–Stephen Sparks, Lit Hub contributing editor

Pajtim Statovci, My Cat Yugoslovia, tr. David Hackston

(Pantheon)

It’s difficult to describe My Cat Yugoslavia, Pajtim Statovci’s debut novel, which will appear for the first time in English in April, but perhaps it’s best to say it shows the fracturing that immigrants may experience in a world that does not want them. The novel deals with intersecting identities: being an immigrant, a Muslim, queer, all of these coming together when a Muslim family from Kosovo is forced to flee to Finland by the outbreak of war. The novel is largely realistic, yet features an anthropomorphic talking cat—distinct from both Murakami’s and Bulgakov’s signature felines—who may be, ultimately, a mirror of the painful, bizarre, isolated reality the protagonist, Bekim, has been forced into. My Cat Yugoslavia is both intriguing and disturbing, a novel from 2014 that perhaps describes 2017 all too well.

–Gabrielle Bellot, Lit Hub staff writer

Thomas Bernhard, Collected Poems

(Seagull Books)

Fans of Bernhard already know him for having an incredibly idiosyncratic, hypnotic, philosophical style in his many novels, plays, and massive autobiography. This unprecedented (in the English language) collection of his poetic output now offers an entirely new vantage on what made Bernhard such a classic writer. A major book, and a long awaited one, this should not be missed.

–Scott Esposito, Lit Hub columnist

Dani Shapiro, Hourglass: Time, Memory, Marriage

(Knopf)

Dani Shapiro’s new memoir Hourglass: Time, Memory, Marriage might already be a classic. I’ve never read a more honest or tender evocation of what it’s like to live with a partner through thick and thin—and there’s plenty of thin, here. Shapiro delves past the sugary crust of love and wedding deep into a bitter core of parenting a sick baby, building a marriage between two ambitious creatives, and coping when one partner makes some unfortunate financial decisions. More important, however, is her non-sugary adherence to her title’s metaphor. Shapiro understands and acknowledges that the longer a marriage lasts, the less time is left in the top of the hourglass. ‘We must be handled with care,’ she writes, and the reader believes that her care in writing is similar to her care in loving. The author’s marriage to M., despite its setbacks, is a beautiful thing. As is this book.

–Bethanne Patrick, Lit Hub contributing editor

Andrzej Franaszek, Miłosz: A Biography, tr. Aleksandra Parker, Michael Parker

(Harvard University Press)

“It is probable that in spite of all horrors and perils,” Czesław Miłosz said in his Nobel speech, “our time will be judged as a necessary phase of travail before mankind ascends to a new awareness.” The basis for this remarkable collective hope is revealed in a new biography from scholar Andrzej Franaszek, which recounts the great Polish poet’s quest for moral substance in the depths of a savage century.

–Dustin Illingworth, Lit Hub staff writer

Norman Podhoretz, Making It

(NYRB Classics)

Was there ever a more glittering apprenticeship than Podhoretz’s to the Trillings, where book reviewer and consummate gossip Diana and eminence Lionel took him under their Liberal wing and introduced him to everyone who mattered among New York’s intelligentsia? And was there ever a more spectacular apostasy than Podhoretz’s, throwing off the yoke of both his mentors and their ideology to form the conservative Commentary and start a competing circle of his own? Making It has it all—drama, class war, lots of politics, more ideology than you can shake a stick at, and at its center the irascible Podhoretz, full of ideals and himself.

–Lisa Levy, Lit Hub contributing editor

Kristen Radtke, Imagine Wanting Only This

(Pantheon)

Kristen Radtke’s forthcoming Imagine Wanting Only This—in its combination of essay, personal narrative, and illustration—is a great example of literary nonfiction’s formal elasticity. Radtke’s drawings are stunning, but her prose, in its lyricism and precision, can feel just as arresting. Her book is an exciting debut that everyone should be talking about.

–Timothy Denevi, Lit Hub contributer

Lidia Yuknavitch, The Book of Joan

(Harper)

“Bodies are miniature renditions of the entire universe,” Lidia Yuknavitch writes in her fierce and urgently-needed novel, The Book of Joan. “We are a collective mammalian energy source.” Yuknavitch is the writer we need at this moment in time. Pick up her latest book and you’ll see why: her sentences sear into your skin, becoming a part of you. (Much like a plot point in the book: in the near future, people write stories on their own bodies.) If you’re a fan of Mad Max: Fury Road, then you’ll love Yuknavitch’s Joan, based on Joan of Arc.

–Michele Filgate, Lit Hub contributing editor

Carl Seelig, Walks with Walser, tr. Anne Posten

(New Directions)

While you will never have the actual pleasure of walking with Robert Walser—walking, of course, being the iconic Walserian activity you would want to partake in with him, given the chance, like watching a bullfight with Hemingway or traveling on the road with Kerouac—the closest you can get to this dream stroll is to read Carl Seelig’s Walks with Walser. Seelig became Walser’s guardian late in his life and his literary executor following his death, after having been a friend and walking companion for years. As W. G. Sebald explained, “That Walser is not today among the forgotten writers we owe primarily to the fact that Carl Seelig took up his cause.” In this book, Seelig meticulously catalogues the details of these walking conversations with the iconic Swiss writer, which makes it an invaluable text for any serious reader of Walser—one that could perambulate alongside his writings as walking companion, fellow flâneur.

–Tyler Malone, Lit Hub contributor

Doree Shafrir, Startup

(Little, Brown and Company)

I tore through Startup in two days. It could’ve been one, but I had to eat, sleep, and feed my cats—all normal activities that became frustrating distractions while reading this book. Written by a veteran culture editor, Startup satirizes and celebrates the current tech moment, entangling the ambitions of an app inventor with the lives of a young journalist and a struggling creative writer. Well-observed and told with a crackling wit, this debut is one of the best I’ve read so far this year.

–Amy Brady, Lit Hub contributor

Filip Springer, History of a Disappearance: The Story of a Forgotten Polish Town, tr. Sean Gasper Bye

(Restless Books)

Filip Springer is an award-winning Polish journalist who he wrote on the nearly forgotten Polish town of Kupferberg. The town survived The Thirty Years War, The Napoleonic Wars, and World War I, but slowly died over the second half of the 20th century. Now, the town is dilapidated and abandoned, with only a few residents still living on the unstable ground above the collapsing uranium mines. Springer catalogs the lost human elements, and the rich history of a town as it disappears. History of a Disappearance contains spooky parallels to the U.S. Rust Belt, Appalachia, and other deindustrialized economies.

–Nathan Scott McNamara, Lit Hub contributor

Freeman’s: Home, ed. John Freeman

This edition of Freeman’s manages to do what the world off the page cannot: provide a place where diversity can safely reside. A sanctuary for stories. For many of the contributors, home is procedural: identifying the steps necessary to make, imagine, define, locate the person, place, song or words that expose their locus; that awaken the internal suitcase or acreage carried, trod or witnessed. Home is immediate

and distanced. Home is often the stories of others. Let these poems, shorts and stories guide you to what is your home.

–Lucy Kogler, Lit Hub columnist

Julie Buntin, Marlena

(Henry Holt and Co.)

It’s rare that a literary novel gives me the feeling that Marlena did. The feeling goes like this: you’re washing the dishes, or walking somewhere, or having a conversation with someone you find mildly boring, and suddenly you feel a little tug, faint but insistent, like you’ve forgotten about something, something you want, no, something you need, now, now, but what is it, and then you realize: oh, it’s this book I’m reading. I must now immediately go back to the world of this novel, and its compelling, compulsory language, and its ice-clean story of two girls, one doomed, one in thrall, and what will happen to drag them both down into traps of their own making.

–Emily Temple, Lit Hub associate editor

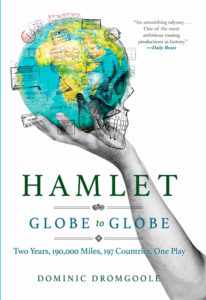

Dominic Dromgoole, Hamlet Globe to Globe: Two Years, 193,000 Miles, 197 Countries, One Play

(Grove Atlantic)

In 2014 Dominic Dromgoole (the former Artistic Director of Shakespeare’s Globe Theater) and his team of traveling thespians embarked upon a two-year global tour of Hamlet. The goal: to bring the tortured Danish prince to every country in the world. They performed in sweltering deserts, ice-cold cathedrals, and heaving marketplaces; through the threat of ambush in Somaliland, an Ebola epidemic in West Africa, and political upheaval in Ukraine. They played in five refugee camps and were the first company to put women and men together on stage in Saudi Arabia. By the tour’s end, Dromgoole and his sixteen actors had shared their love of Shakespeare with over 225,000 people in 197 countries and the project had been granted UNESCO patronage for its engagement with local communities and its promotion of cultural education. The account of all this sounds like one hell of an adventure.

–Dan Sheehan, Book Marks editor

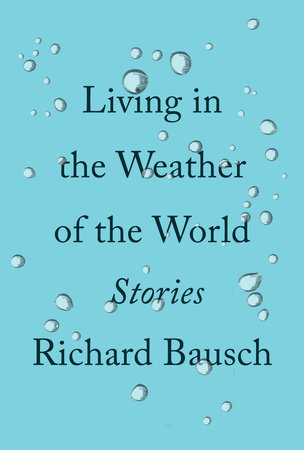

Richard Bausch, Living in the Weather of the World: Stories

(Knopf)

Six of Richard Bausch’s stories in Rare and Endangered Species have been mashed-upped in the new film, Espêces menacées (Endangered Species) by Gilles Bourdos (not yet released), and Bausch was surprised to see how the filmmaker managed to connect such disparate pieces. As a reader of his work, I was not. Bausch is above all, a storyteller, as anyone who has ever shared a whiskey with him knows (which is many of us). Whether in conversation or on the page, he’ll spin a yarn about the most mundane thing and he’ll end up eating Chicken Cordon Bleu with Eudora Welty, and somehow, it all makes perfect sense. With enormous generosity and a little magic, his stories connect small acts of humanity with large acts of grace. His latest short story collection, Living in the Weather of the World, appears to do just that. In the first story, “Walking Distance,” he covers the ground of a marriage gone sour—at least for the bride, whose husband’s super-sized fondness for her has morphed into an unappealing submissiveness—and we end with a compassionate scene between two desperate men, dangerously close to killing each other. The collection ends with “Still Here, Still There,” about two elderly World War II veterans from opposing sides who reunite (thanks to a meddling son), and like dealing with the ‘weather in the world,’ they make do with what they have. Required reading.

–Kerri Arsenault, Lit Hub columnist