Writing Middle-Aged Love

"There’s Comfort in Recognizing Us as Unremarkable, Part of the Big Wheel of Life"

Pity the creative writing students starting the University of Arkansas MFA program in 1994. Pity them, for on the first day, two of the 12 fell in love. And the other ten had to read about it for the next four years.

I was one of those smitten kittens, 23, studying poetry. My husband-to-be, 30, was studying fiction. The son of a mechanic, he was finishing a book set in the rough Alabama chemical plants and grit factories where he worked while earning his B.A. at night. His characters were the people he’d worked alongside, though for fun he’d sometimes slip me into the back of the bar, a redhead leaning over a pool table, sporting a lizard tattoo.

I, meanwhile, snorting hits of Sylvia Plath, lodged Tommy at the center of everything I wrote, as he was at the center of everything I felt, and everything I felt had never been felt before. For example: I was pretty sure we invented sex. You can imagine the kind of insufferable classroom environment this must have created for our cohort. Though suffer it they did, in pursuit of their Masters. Liz, Otis, Sandy, Gary, David, Geraldine, Michael, Don, John, and Carolyn: if you’re reading this, forgive me.

Because I’m describing that pair of lovebirds and their creative output in the simple past tense, you might assume that I quit him, or quit writing, or both. But we celebrated our 19th anniversary in May, and we’ve each published five books (including one novel we wrote together). I’m describing that pair in simple past simply because our past seems unrecoverably simple. Our present is wonderfully complicated with careers and busy lives and, most of all, the publication of three small humans: our children.

So while I still write about our relationship, I’m not sure my old classmates would recognize us. My tone is less earnest, and Tommy’s role has been decentralized, and I’ve fallen hard for the sentence, instead of the poetic line. Prose somehow seems the best vessel to contain the various textures of these complex interactions; nonfiction prose, because I’m hewing to the restrictions of truth; bite-sized nonfiction prose, because I’m more interested in teasing out the complexities of the moment than welding moments into the Freitag triangle. “Micro-memoirs” is the name I’ve come up with for these bite-sized nonfiction pieces that explore moments I couldn’t have imagined mattering back when Sixteen Candles circumscribed my erogenous zone.

*

Once last year I was out on a long run and tripped over a speedbump. My wipeout was spectacular and airborne, ending with obscenity and a gravel-spraying skid. I limped home, blood rivering down my shins from split kneecaps, and my left palm mangled like hamburger meat. Tommy was there and sweetly washed my wounds. Afterward I went to teach my class. Over the following days, my knees healed, but my palm looked bad. I figured that, with the aforementioned three kids, I simply couldn’t manage to rest it. But eventually my palm scabbed, hardening into a thick puckered star that itched. Over the next weeks, the star began to shrink until all that was left was a weird white blister, puffy, with a black lump at the center. When this blister decreased neither in size nor hue, I began to have the discomfiting feeling that the black lump was a foreign object. My five-year-old wouldn’t hold my “bad hand” on the walk to pre-K.

Finally I went to the health center on campus, where the examining G.P. told me I needed to see the hand surgeon. In Jackson. About three hours away.

Losing an entire day to remove a black thing from a blister? Not hardly. “Couldn’t we just, you know—” I made a fork-and-knife sawing motion.

“Well,” she said, considering. “Let me see if Dr. Yates is in the building.”

“Shoot,” Dr. Yates drawled, a few minutes later, palpating his fleshy thumbs around my palm. “We got this.” He had me lie back and gave my hand a shot and then yelled for his nurse to bring his “scalpel with the claws.” Thus began the play-by-play that included “Almost got it” and “Whoopsie” and “Slippery little devil” and “You know, I started out as an English major.” I could take the pain, but not the narration. I began to think I might pass out. Finally, after he said, “I’m just gonna rummage around in here until I nab it,” I told him I was glad he was taking care of me but hoped he could continue silently.

He didn’t speak again until he said, “Lookee here.”

When I opened my eyes, he pointed to a surprisingly neat incision in my palm, like a slit for a dime. Proudly, he bandaged me, then handed me a plastic syringe. Inside its calibrated tube, the jagged piece of gravel.

I ended up writing about this in a micro-memoir called “Married Love,” part of a series. My former classmates might wonder at the title’s relevance by this point, because we haven’t seen Tommy since the washing of the wounds. But if Tommy’s role in this piece, as it sometimes is in life, has been pushed to the day’s intro and concluding paragraphs, that doesn’t mean he’s any less central emotionally. In fact, it’s because I know he’ll still be there when I get back that I have the confidence to decentralize him in the first place. The tension in my grad school yawps was fueled by insecurity, by the fear that our passion could expire at any minute. Now, tension in my life (and work) comes from outside sources. Often, love is where I go to retreat from it.

So. I drove home from the clinic, excited to find him in the kitchen so I could tell him my story, show him my bandaged hand. I held up the syringe with the gravel, flicked it to rattle it, and we laughed a little.

He said, “What are you going to do with it?”

“Do with it? I’m going to pitch it.”

“I want it.”

“You want it?”

“Yeah. I want it. I want to keep it. I’ll put it in my office.” He paused, then said, “It was in your hand for a month. It was a part of you.”

*

When I was a dreamy teenager, I despaired at the marriages around me, stripped of erotic intensity as they were. Where was the passion? Now I know that it was there, I simply didn’t recognize it: a failure of imagination on my part. Pressing a prom corsage? Romantic. Saving foreign matter that the spouse’s tissue has absorbed? Yuck.

Yuck, as it turns out, provides tension in these middle-aged love songs. The sentence provides the engine, less artfully shaped and self-aware than the poetic line, better able to maintain its slow burn even with colloquial fuel, the inclusions of the every day, the gravel-in-the-palm. The short form becomes a lens to magnify the intimacy of the interstitial: The time we lowered onto the December-cold pleather seats of our used minivan and knocked hands, both of us reaching to turn on each other’s seat warmer first. Or the morning I bought a bag of frozen peas to numb Tommy after his vasectomy. (Followed by that evening, when I added the thawed peas to our carbonara.)

Aging: yuck. Aging together: yuck squared, but cut with the sweetness of being privy to the beloved’s vulnerabilities. The indignities of illnesses and injuries. And the intimations that there will only be more to come (if we’re lucky—while I’m referring to us as “middle age,” at 45 and 53, let’s face it, true middle age is in the rear-view.) Mortality can’t be vanquished through denial, so it might as well be lanced with humor. Laughing together: the great aphrodisiac. We didn’t invent laughter, just as we didn’t invent sex, or anything else for that matter. There’s comfort in recognizing us as unremarkable, not a singular pair but part of the big wheel of life. So I’m writing intimately for anyone interested in the intimacy of committed love, which still doesn’t capture our culture’s attention. Forty-Six Candles is a star-studded movie being filmed right now by nobody nowhere.

I teach my own MFA students now, and it’s not hard to assume, if they spy Tommy and me giving each other a quick hug, that they don’t see erotic intensity. Fair enough. But what they couldn’t guess—unless perhaps they end up reading the “Married Love” sequence—is that when I hug him, my hand finds purchase (automatically, reassuringly) on his back cyst. Yuck? Yes. But isn’t it romantic to think so.

__________________________________

Beth Ann Fennelly’s collection of micro-memoirs, Heating & Cooling, is available now from W. W. Norton.

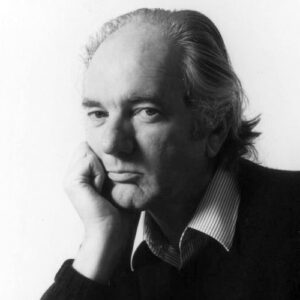

Beth Ann Fennelly

Beth Ann Fennelly is the author of three poetry collections, Unmentionables, Tender Hooks, and Open House; two memoirs, Heating & Cooling and Great with Child; and a novel,