What Was the First Book You Fell in Love With?

The Center for Fiction’s 2017 First Novel Prize Authors Weigh In

We asked this year’s Center for Fiction First Novel Prize shortlisters about their earliest love affairs with reading. Meet them all at this year’s Center for Fiction Fete, December 4 at the Center for Fiction.

![]()

Bethany Ball, author of What to Do About the Solomons

The Wizard of Oz series, L. Frank Baum

Every Easter night, as far back as I could remember, I would watch The Wizard of Oz on an ancient black and white television at my grandparent’s house. Each spring break, my mom and I would visit her parents in Craggie Hope, Tennessee, where my mother had grown up. The Wizard of Oz, back then, was my favorite movie.

It was my father who gave me the first few Oz books. He’d been trying to get me to read the old books he loved so much as a child: Treasure Island, Swiss Family Robinson, Gulliver’s Travels, Mark Twain, and Ray Bradbury. But besides Tolkien, none of them interested me until he handed me The Wizard of Oz. Years later I realized it was the only book he gave me that had girls in it.

There were 14 Oz books in all. I loved Princess Ozma best. I loved Dorothy Gale too, but I could never really forgive her for wanting to go back to Kansas. I was a Midwestern girl myself and used to the tornado warnings that had us running for our basements. Tornados were frightening, but I figured if I ever got caught up in one and found myself in as fantastic a place as Oz, I would never come home. My aunts, upset we didn’t join them Easter Sunday at church on our yearly visit, would ask if I wanted to go to heaven. Well, don’t you? I’d nod my head, and squirm away shyly. But alone to my parents, and to my mother’s apparent delight, I would say,

When I die, I’m going to Oz.

![]()

Julie Lekstrom Himes, author of Mikhail and Margarita

A Wrinkle in Time, Madeleine L’Engle

My serious reading life began when I was seven and relegated to an antique rocking chair after school every day for 20 minutes of quiet reading. This required-reading stopped being torture on Day 2, as I got lost in the backwoods of Wisconsin with Laura Ingalls and her sister Mary. Torture then became our annual summer trip to the wilds of Northern Minnesota where the nearest library was 20 miles away and the only books to be purchased were Harlequin romances from the local Ben Franklin. My parents would complain of the piles of books that filled the foot wells of the car’s backseat in preparation for this trip. Somehow bike riding, swimming in the old mill pond, raising farm animals and driving a tractor were supposed to be sufficiently entertaining.

Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time was one of my first literary loves, traveling with Meg Murry, little brother Charles Wallace, and the gangly but trusted Calvin O’Keefe as they followed Mrs. Whatsit through time and space, because you know, lamb, there is such a thing as a tesseract. “Go back to sleep,” says Meg on page 4 to the cat. “Just be glad you’re not a monster like me.” To my 12-year-old self, who like Meg had been befitted with braces and difficult hair and the inability to be cool or at least invisible, her words found me the way one finds a friend. Then, a heartbeat later, the realization—this was what I’d been reading for.

But chief among these was E. L. Konigsburg’s From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, wherein the plucky but careful sixth grader, Claudia Kincaid, with her younger brother Jamie, run away from home to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. From the start, I had to admire Claudia—what a magnificent destination she’d chosen. In my own plotting of such a venture, I could devise of nothing better than to hide in one of the many daysailers tied along the small dock of the manmade lake in our town of Westlake, California. I imagined chilly nights lying in the hull of some boat, the sound of water lapping against the fiberglass, and I weighed the warmth of my own bed against the need to enforce some new sense of appreciation from my parents.

Claudia knew from the start that her adventure would be short, and her leave-taking a means to compel her own distracted parents not to take her for granted. Yet as we read, we sense that her need becomes something a bit different, something more adult-like. It isn’t really about gaining some sense of approval; rather a yearning to discover and understand the potential for her own relevance. This is where her desire transcends to all readers. I have pursued both science and creative writing, two seemingly disparate disciplines, yet they are not at all different. When Claudia discovers the secret to Angel, the statue which The Met has purchased from the reclusive Mrs. Basil E., we understand, as she does, that discovery is very much like creation. We are both making up and making sense of our world as we go. Even my own Margarita engaged in that same journey. Perhaps that’s how she found me—that’s why she invited me along. Perhaps that’s what we hope our characters—like best friends—will do.

![]()

Jaroslav Kalfar, author of Spaceman of Bohemia

The Fellowship of the Ring, J.R.R. Tolkien

There’s no getting around it—as a child, I was a thief. I began at the age of 11 by stealing prepackaged baguettes and candy bars from the market across the street from school. This way, I could avoid eating the often-gruesome meals at the school cafeteria (this was a Czech cafeteria, not an American one, and thus the American lunch choices of hot dogs, tacos, and sloppy Joe’s were denied to me in the interest of nutrition. My options were boiled carrots with beef, dill cream sauce, the stuff of nightmares) and look impressive to my friends at the same time.

But my thieving ways were interrupted when I was caught by security and chased out of the store. Around this time, a new bookstore opened in the same strip mall, right above the food market. Here my friends and I obtained our first Dungeon and Dragons manuals and here I continued my life of crime by stealing my very first novel. The Fellowship of the Ring by some person named Tolkien. It came highly recommended by an older friend, and I couldn’t resist the fresh white pages, their smell, the green cover decorated in golden Elvish letters. I took off my hoodie, slipped the book inside, and walked out.

I had loved books (from Robinson Crusoe to War with the Newts to everything by Verne—adventure was the keyword) and writing before I discovered Tolkien, but it was with The Fellowship that I discovered the real power a book can have over a person. I neglected my school duties, my friends, and my chores, I was annoyed at the concept of sleeping because I just wanted to get back to reading. Here was a beautiful world beyond my own where the ordinary and small could become heroes, where every minor action had a world-changing consequence. Not only was the story fascinating, gripping, and booming with imagination, the basic requirements most children have for their books. It seemed to have something to say about the world at large, my world, the life I would be living, and though I didn’t understand what that meant at the time, I was at the brink of discovery.

I came to the United States a few years later, rather abruptly, without any planning. I was lost, disconnected from the language and from the culture. In my one medium suitcase, I brought a single book. Its green cover decorated by golden Elvish letters. I read it through sleepless nights to distract myself from the constant sense of loneliness and loss of the old country. Characters in books often embark on unknown journeys. The unknown is their catalyst and their greatest obstacle and their biggest reward. When I picked up my first book in English at a high school library in Florida, I too was embracing the unknown. Reading The Fellowship in English was one of the most frustrating, discouraging things I have done, but I got through it. It helped to have my worn copy in Czech side by side, nearly memorized, so the words of the English version were still familiar even when they made no sense. It was no longer just a book—it was my partner in crime, my translator, my first ticket to the language in which I now read and write.

Not only is this the first book I truly loved, it is the one book I have loved unfailingly all my life. Books of such power deserve an entire library section of their own, so they can always be at the fingertips of children who might need them most.

![]()

Annabelle Kim, author of Tiger Pelt

Green Eggs and Ham, Dr. Seuss

“If Mommy puts a rock on your plate, you eat it!” my father used to bellow (unappetizingly) at dinner time. Having endured the Japanese occupation, having come of age during the Korean War, having witnessed the ravages of hunger, he was not about to allow a child of his to go malnourished. Not in America.

To this day, I shudder to recollect the hours hunkered miserably over our plates, laboriously putting away raw liver, served because some Korean lady told my parents it made children smart. Smart? Did somebody say smart? In no time, my sister and I were served a massive slab of quivering raw liver bleeding onto an oversized plate. We cut it into bite sized blood clots, placed the bits at the backs of our tongues and swallowed them whole with slugs of water. Refusing was not an option.

In our house, even innocuous hamburger stirred a disquiet in our little gullets. As soon as the patties had hit the frying pan, the dubious odor signaled that it would taste nothing like a farmed product. How could our freezer have filled to the brim overnight with burgers when we could scarcely afford a single package of beef? It had to be road kill. I just knew it. I could practically taste the asphalt.

If the problem was not about quality, then it was quantity. Even the most refined and processed child-friendly meal was bound to be cause for despair. For breakfast, the Kim offspring were forced to consume a tall glass of ice cold whole milk, a tall glass of ice cold orange juice, a grapefruit half, and a towering bowl of cereal so precariously heaped that one feared to insert a spoon lest a landslide occur, whereupon we sloshed heavily to the bus stop, the breakfast slurry rising up our pipes and threatening to overflow with every step. While we worked on stuffing our cereal chutes, my father compulsively re-organized the contents of the boxes, consolidating the multi-grain with the rice squares and the shredded wheat with the granola so you never knew what mixture would come out when he poured. The boxes had to be bulging; there could never be any partially empty boxes of cereal.

I loved Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham because I admired and envied the unnamed fuzzy curmudgeon in the top hat who declares with unapologetic disdain, “I do not like green eggs and ham.” Pursued by pesky preachy Sam-I-am, a character I yearned to deliver a swift kick to the shin, the fuzzy curmudgeon abandons his armchair and stalks off in a huff. Sam-I-am pursues and cajoles the finicky eater. Fuzzy curmudgeon raises his fist, shouts, and runs far away from the unnatural food.

I had elaborate daydreams of defying my father and flying out the door, out into the street, over the hills, far away from the thrice-daily forced gorging. When I grew up, I was going to be just like this fuzzy curmudgeon. I was never going to eat anything but pizza and ice cream in perfect portions.

In my self-serving manner, I filtered out the parts of the book I did not like, namely the denouement, wherein Sam-I-am finally browbeats my hero into trying the green eggs and ham. Lo and behold, after one miraculous bite, the fuzzy curmudgeon transforms into a smiley health nut with a spring in his hairy step. He vows to eat the vile-looking meal here, there and everywhere, with a fox and a mouse for dinner companions. Such craven capitulation was not my idea of satisfaction.

The other day, I noticed that my triplet boys were swallowing their broccoli whole with swigs of apple juice. To my surprise, I heard a furious parent (me) bellow, “You have to chew the veggies or you don’t absorb the nutrients!” Sometimes you just cannot understand your father until you become him. And, yes, I confess. When I read Green Eggs and Ham to my children, I recapitulated the try-new-foods teaching moment ad nauseam until someone finally complained, “Mom, we get it!”

I do too. Don’t tell my kids, but I will always have a soft spot for that fuzzy curmudgeon.

![]()

Simeon Marsalis, author of As Lie Is to Grin

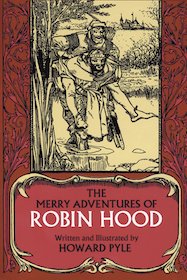

Animorphs: The Invasion, K.A. Applegate

The first book I ever fell in love with was Animorphs: The Invasion by K.A. Applegate. I didn’t know it at the time, but K.A. was two people, Katherine Applegate and her husband, Michael Grant. The tandem created 54 books from 1996 to 2001 (I was six when the first one came out). The series centered on a group of kids who were fighting a hostile alien takeover of the earth with their ability to morph into any animal they wanted and the help of their docile alien friend, Axe. I don’t remember the plot of that first book. The holographic cover felt far beyond our time. The holographic cover seemed to be a document from the future. Boys loved it, even with the clunky themes (children could only change into animals for two hours at a time). Many students made their parents buy the newest book in the series at the Daniel Webster Elementary School Book Fair.

After a year, the texts became less important than your possession of them, though I doubt my love for the book was ever pure. All of my friends had a copy. After some number in the series, I began to lie when people would ask if I had read the new Animorphs. The authors wrote more prodigiously than I could read. Then, Harry Potter and The Sorcerer’s Stone came out. We stopped buying Animorphs. Still, I remember lying on my childhood bed and learning about those evil Yeerks. Their bodies were shaped like slugs. They burrowed into the human brain and controlled their hosts. The only defense against their evil plans were the Andalites—that sacred race of alien centaurs with blue fur who communicated through telepathy—and the Animorphs. The cover of that first book has a young Caucasian boy transforming into a lizard. That book had a deep impact on my young psyche. Now that I think about it, I got a pet iguana in the late 90s. I don’t remember making that connection, but so many years have passed since then. He ran away.

Susan Rivers, author of The Second Mrs. Hockaday

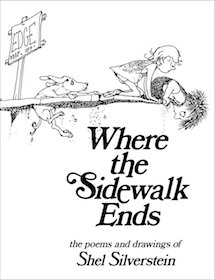

The Adventures of Robin Hood, Howard Pyle

None of the books I read as a child have survived to the present day. Late in her life my dear mother developed dementia and became a hoarder; everything I once possessed in the house where I grew up was carted to a toxic-waste dump by the county hazmat crew. I suspect it would have been difficult to pick a favorite even if the books had survived: my sisters and I were voracious readers and were kept amply supplied by our Aunt Helene, a book editor at the San Francisco Chronicle. Every Christmas she shipped us—her poor relations—a box of reviewer’s copies of fiction and non-fiction titles, sometimes appropriate for children and sometimes less so. I recall a biography of mad King Ludwig II of Bavaria, a collection of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations of wood sprites, and a how-to guide for making macramé clothing, with which I entertained a mild obsession. (Is there anyone left who knows what “macramé” is?)

I don’t know if The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood was a gift from our aunt or if it had once been Daddy’s own, but I suspect the latter. That’s because we were not allowed to treat it with anything less than careful, clean-handed reverence. Our father was an artist: a creative misfit and traumatic brain injury survivor. All his life he maintained that his elder brother lured him on to the roof of Horace Mann Elementary School to fly a kite with the express intention of killing him, which was nearly the result. He treasured his Scribner’s edition with Howard Pyle’s intricate engravings; mostly what I remember from that book was the final illustration of a weakened Robin propped up on a pillow, drawing his bow in order to “shooteth his last shaft” through the open window. I pored over that picture, marveling at its tragic implications. That was my introduction to metaphor.

My father, while not comfortable in a traditional parenting role, nevertheless took pleasure in outfitting our childhoods with sublime props. He built a Sioux-style teepee large enough to accommodate us and our sleeping bags in the backyard on starlit nights, and during our Robin Hood period, crafted four beautiful bows and arrows by hand out of ash-wood, our names tooled on the grips. I would give anything to hold my bow in my hands today and “shooteth a shaft,” but the bows went to the dump along with the books, the teepee and the macramé vests.

The story of Robin’s merry band of men robbing the rich and giving to the poor is well-known, however, what I absorbed in powerfully affirming terms from this tale was not so much the noble aims of the band and its leader as much as their existence as outsiders, living in the woods far from the long arm of Nottingham’s authority and its conventions. This was a state I could relate to, as did my sisters, and we clung to Robin Hood’s alternate reality in order that, by identifying with outsiders, we felt less like outcasts. We were strange children, isolated by the circumstances of our parents’ complicated relationships with their own families, their bizarre ideologies, and their decision to settle on a former cattle ranch in a house my father designed, where coyotes howled outside our windows at night and rattlesnakes occasionally curled up beneath our baseboard heaters. And then, regrettably, I wore those macramé creations to school, along with the lederhosen I acquired during my Heidi craze. Even without the lederhosen, classmates who heard me speak aloud asked me “what country do you come from?” Not surprisingly, my best friend in high school was the librarian, a wild Alabamian who once put a loaded Colt revolver in my hands and taught me to shoot the shit out of a Jeffrey pine. In her own way, I believe, she was teaching me that being strange might one day prove to be my salvation.

Growing up as an outsider has its advantages. When my husband and I decided to move to North Carolina from San Francisco two decades ago, everyone we knew told us we were crazy. (Years before, some of the same people told us we were crazy to marry each other.) But if you are not bound by convention, you are more willing to take risks. My protagonist Placidia Hockaday is asked to explain why she married Major Hockaday after knowing him for only two days, taking on the care of his child and his farm while the Civil War raged, stepping blithely into the abyss of the unknown. She replies to her cousin: “life is all about the leaps.”

So it has been for me: an outsider still, but ready to leap, not knowing where I’ll land.

![]()

Kaitlin Solimine, author of Empire of Glass

Where the Sidewalk Ends, Shel Silverstein

For some unidentified reason, as a child I only read while sitting on my bedroom floor or cloistered in my crowded closet, a copy of Judy Bloom’s Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret or Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins held close. In my preteen years, female protagonists, like Anne in my beloved hardcover Anne of Green Gables series, drew me into a world that felt almost within my grip—a world beyond rural New Hampshire, of girls on the verge of womanhood, strong, adventurous, sharp-tongued girls.

And yet, as an adult, when I think of my childhood, I yearn to revisit one of my most treasured possessions—Shel Silverstein’s Where the Sidewalk Ends. I have abiding memories of my Godmother, Grace, a schoolteacher who reveled in the fanciful magic of Silverstein’s poetry, reading me the rhymes of “Sick:” “What’s that? What’s that you say? / You say today is… Saturday? / G’bye, I’m going out to play!” (And perhaps no coincidence of romantic fate my husband still recites this poem by heart.)

Revisiting Silverstein, I find a philosophical and political bent in his work and wonder if that may have been the reason he drew me in as a child eager to leave my bedroom, slowly becoming aware of the complications, the blurred lines of life outside the walls of my all-white, conservative-leaning New England town.

In “The Long-Haired Boy,” a boy with long hair is ridiculed until his hair turns into wings and he flies away, a town hero. [Message: difference can be a strength.]

In “No Difference,” the message is obvious: “Small as a peanut, / Big as a giant, / We’re all the same size/when we turn off the light.”

In “Forgotten Language,” an “I” bemoans a forgotten ability to speak the language of flowers, caterpillars, starlings—an ode to not only childhood presence but also lost connections to the natural world.

The spare, almost crude, black and white sketches call to me from the page, reminding us childhood can feel the loneliest place and yet also be full of possibility and wonder. Silverstein’s poetry, a beautiful departure from the drone of prose books, even plays with the space of the page itself, with writing as an act of material (and at times, futile!) art, as in “Lazy Jane,” where the words themselves fill a thirsty girl’s mouth, or in the text layered atop a giraffe’s neck: “Please do not make fun of me and please don’t laugh it isn’t easy to write a poem on the neck of a running giraffe.”

At its core, Silverstein’s poetry bursts with a simple question, the same one children regularly ask adults: “Why?” We join him on an adventure to that place where this question meets its conclusion, where the sidewalk ends, accepting his opening poem’s invitation–

If you are a dreamer, come in,

If you are a dreamer, a wisher, a liar,

A hope-er, a pray-er, a magic bean buyer…

If you’re a pretender, come sit by my fire

For we have some flax-golden tales to spin.

Come in!

Come in!

Isn’t this what all literature—and life—invites of us? The ability to dream of the impossible, to question what is, build a new scaffolding beyond the broken frames we’ve inherited (as in Silverstein’s “The Generals:” “Said General Clay to General Gore / Oh must we fight this silly war? / To kill and die is such a bore.”)

Now, as mother of an almost-two-year-old, I’m regularly deciding what books to read her, how I’ll shape her literary inheritance. One of our favorites is Animus by Seonna Hong, a moving picture book sharing the fancifulness, and blurred lines, of Silverstein’s poetic philosophies. Animus concludes with a telling, necessary lesson for children and adults alike, speaking to the power, and futility, of literature:

Knowledge is a sword,

but it’s also protection.

For what is important,

and this should be mentioned:

It’s not the sharp words,

the claws or the fangs,

It’s what we do to ourselves

that causes the angst.

There are few happy endings

all tied up in bows.

A full life is marked

by the highs and the lows.

And maybe it’s just about

finding our way

Through all of those wonderful

shades of gray.

In today’s complicated, not always “fair” world (fairness: a preoccupation of children and adults alike!), it is my hope literature provides children with narratives and language to navigate the power structures they inherit, perhaps providing hints as to how to create a more equitable, empathetic, responsible society. I’m grateful for authors like Silverstein and Hong who guide us there along the ragged paths, the sidewalks with, and without, ends.