Was Edmund Wilson Just Jealous of Lolita?

How a Great American Literary Critic Got it Wrong About a Classic

In 1946 Edmund Wilson published his second novel, Memoirs of Hecate County. Like a much more successful “sexy” novel that would appear roughly a decade later, Hecate—a collection of eight related stories, several of them quite long—had some eloquent descriptive passages, and some downright baffling parts. “Mr. and Mrs. Blackburn at Home,” for instance, included an eight-page block of text in untranslated French. But, as it would be for the still-aborning Lolita, readers did not seize on Hecate for the innovative character sketches or for the intriguing digressions into French prose. Readers flocked to it for the sex.

Mainstream literary mores after World War II differed immensely from what they are today. We are condemned to live forever inside the old Cole Porter song: “Anything Goes.” In Wilson’s time a glimpse of stocking—or in the case of Hecate, a flash of a woman’s “mossy damp underparts”—was awfully shocking. As he was to discover, anything did not go.

Hecate, which Wilson called his “favorite among my books—I have never understood why the people who interest themselves in my work never pay any attention to it,” has not stood the test of time. Even Wilson’s friends thought he was a programmatic novelist, meaning that his fiction seemed to be trying to prove something, or to be illustrating a theory rather than telling a story. (One could level that same criticism at much of Nabokov’s fiction.) The scandalous sex scenes now seem like a glimpse of a naughty picture in a turn-of-the-previous-century stereoscope. Of archaeological interest, and not much more.

When Hecate’s protagonist finally beds “The Princess with the Golden Hair,” in one of the stories, he writes that her nude body

. . . did really resemble a Venus. Not only were her thighs perfect columns, but all that lay between them was impressively beautiful, too, with an aesthetic value that I had never found there before. The mount was of a classical femininity: round and smooth and plump; the fleece, if not quite golden, was blond and curly and soft, and the portals were a deep tender rose.

And so on. What is curious is that in between the isolated and brief episodes of lovemaking, the protagonist holds forth on any number of subjects not guaranteed to entrance young ladies. The narrator, a thinly disguised Edmund Wilson, regales the working girl, Anna, with lectures on the Russian Revolution and the role of the proletariat in a capitalist society. He woos Imogen, the golden-tressed, stay-at-home suburbanite, with talk “about Goya and his queer imagination and his affair with the duchess of Alba.”

“You talk so brilliantly,” Imogen tells our hero. “You’re really a brilliant man, aren’t you?” These must have been words that Wilson had heard during amorous encounters, and we know from his own pen that he loved to run his mouth at inopportune moments. In his journal The Forties, he recalls questioning a French whore in London at such tedious length that “she finally got out her knitting.”

Hecate got bad reviews. “It is not a good book,” Alfred Kazin told Partisan Review readers. Cyril Connolly, whom Wilson considered a friend, wrote that the author’s sexual “descriptions, mechanistic and almost without eroticism, achieve a kind of insect monotony.” The New York Times ignored the novel; Wilson learned that the higher-ups had spiked a favorable review. Years later Wilson’s New Yorker colleague John Updike, no stranger to lubricious prose, wrote that “there was something dogged and humorless about Wilson’s rendition of love; the adjective ‘meaty’ recurs.”

Nabokov called the book “wonderful,” and claimed to have read it in one sitting. (Wilson had told him that he appeared in a tiny cameo in one of the stories, as “the clever Russian novelist” who may have known Mr. Chernokhvostov, “Mr. Blacktail,” possibly the Devil, in Europe.) He was not the only reader—Alice B. Toklas was another—to detect an undercurrent of tortured Puritanism in the sexual encounters. “The reader . . . derives no kick from the hero’s love-making,” he wrote to Wilson. “I should have as soon tried to open a sardine can with my penis. The result is remarkably chaste, despite the frankness.”

When Nabokov unleashed a shot like this he knew to expect a return volley, with plenty of pace. “You sound as if I had made an unsuccessful attempt to write something like Fanny Hill,” Wilson answered. “The frozen and unsatisfactory character of the sexual relations is a very important part of the central theme of the book—indicated by the title—which I’m not sure that you have grasped.”

The intellectuals caviled, but the public didn’t. The book sold fifty thousand copies in its first few months of publication, swelling Wilson’s perennially depleted coffers. It also made him much more famous. He was already New Yorker–New Republic famous, well known to discriminating readers. Now he was national-best seller famous, with a book alternately hailed and denounced in newspapers across the country. “I’m making no end of money,” he wrote to a friend in May 1946. In a different letter he said, “I am counting on my new public of sex maniacs to buy 100,000 copies.”

But Wilson and money were never destined to share a taxi-cab. Not in 1946, and not ever. The powerful newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst had embarked on a campaign against “indecent books,” attempting to mobilize Catholic readers, and Catholic officeholders, against novels like Hecate County. In July the New York City police, acting at the behest of the Anti-Vice Society, a cat’s-paw of Hearst and New York’s Cardinal Francis Spellman, seized 130 copies of the book. Wilson’s publisher, Doubleday, obtained a restraining order, and Wilson’s friend John Dos Passos organized a committee to support his former comrade’s First Amendment rights. The hoo-ha galvanized sales, which eventually totaled sixty thousand copies. In the fall Wilson burst in on his friend, the poet Louise Bogan, calling for her very finest brandy, explaining that “I am so rich and have the gout.” He confided to Bogan that Doubleday would probably lose its court case against the Anti-Vice Society, and that he wouldn’t be rich for long.

He was right. The sex maniacs would have to wait. In October 1946, despite eloquent testimony on Wilson’s behalf by the literary critic Lionel Trilling and others, New York’s Court of Special Sessions banned the sale of Hecate. An appeals court affirmed the decision. Wilson was out of the chips. The ruling “is an awful nuisance and is putting a crimp in my income,” he informed Nabokov. The case found its way to the Supreme Court, which deadlocked 4:4 on the obscenity question, with Wilson’s friend Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter recusing himself from the case. Wilson was irate, and complained to a friend that “Felix was an old faker and that [he] never wanted to see him again.”

Quod scriptum, scriptum est. What had been written, was written. Wilson used the cash haul from Hecate to finance a lengthy stay in Reno, Nevada, for himself and his future (fourth) wife, Elena Mumm Thornton. The marriage would be his most successful and last until the end of his life.

*

Lolita had a complicated genesis, which involved Wilson in several different ways.

Nabokov had addressed the subject of young-girl love in a 1939 not-short story, “The Enchanter,” written in Russian in Paris and never published. (Deep-dish Nabokovians know that the author teased the “Enchanter” plot in a brief passage of The Gift.) Nabokov supposedly lost “The Enchanter” in his move from Europe to the United States, then found the manuscript, which he deemed unfit for publication, in 1959. In a 1947 letter to Wilson, Nabokov mentioned that he was working on two projects, a “new type of autobiography,” the future Speak, Memory, and “a short novel about a man who liked little girls—and it’s going to be called The Kingdom by the Sea.” That was a preliminary title. Eventually he called it Lolita.

Nabokov mentioned the book twice again to Wilson. “In an atmosphere of great secrecy,” he wrote from a summer butterfly-collecting trip in Oregon, “I shall show you—when I return east—an amazing book that will be quite ready by [the fall of 1954].” A few months later he promised Wilson that “quite soon, I may show you a monster,” meaning Lolita.

Approaching this theme for the second (or third) time while working on other book projects, including the massive Onegin translation and research, and teaching a full course load at Cornell, Nabokov took seven or eight years to write Lolita. The novel emerged as a far more sophisticated work of fiction than “The Enchanter,” which Dmitri Nabokov published as a novella after his father’s death. For instance, there are no named characters in “The Enchanter,” just “the man,” “the widow,” “the girl,” and so on. No nefarious Clare Quilty, no rootless and bootless Humbert Humbert, no mixedly motivated Charlotte Haze, and of course no All-American gal, Ms. Dolores “Lolita” Haze-Schiller herself.

In June 1948, as part of their occasional, comradely exchange of erotic literature, Wilson sent Nabokov a 106-page document, “Confession Sexuelle d’un Russe du Sud,” which the psychologist Havelock Ellis had appended to the sixth volume of the French edition of his Studies of Sexual Psychology. Deemed to be an authentic document, the memoir recounted the sexual odyssey of a young, wealthy Ukrainian who lost his virginity at the age of twelve, having been seduced both by girls his age and by older women. Knocked off the path of conventional education by his sexual compulsion, the narrator rights himself as a young man and obtains an engineering degree and a respectable fiancée in Italy. Alas, during a business trip, fate conspires to introduce him to Naples’ worldly and aggressive corps of teenage prostitutes. He becomes addicted to their services, succumbs to the compulsions of his youth, and sees his marital prospects disappear. The confession ends on a note of despair: “He sees no hope of ever mastering his drives in the future,” according to Simon Karlinsky, who researched the Ellis connection in detail.

We know that Nabokov read the Ellis tale closely, because he referred to it twice, once in Speak, Memory and a second time, in greater detail, when he translated and reedited Speak, Memory as Drugiye Berega [Other Shores], into Russian.

While noting that Nabokov had already mentioned the Lolita project in 1947, Karlinksy writes that “Nabokov’s reading in June 1948 of the nymphet hunter’s confession published by Havelock Ellis may well have provided the additional stimulus for the next stage of the book’s development.” Wilson clearly thought he had exerted a gravitational pull on Lolita’s long trajectory from notion to novel. There is, for instance, this undated letter in his Yale archive:

Dear Volodya,

It lately occurred to me that I have not been sending you the nyeprilichnuyu literaturu [“indecent literature,” written in Russian] with which I used to supply you, and which no doubt inspired Lolita, so I am enclosing this in my Christmas packet.

[Emphasis added] Nabokov had finished Lolita by the summer of 1954. He was eager for Wilson to like it. “I consider this novel to be my best thing in English,” he wrote to Wilson, “and though the theme and situation are decidedly sensuous, its art is pure and its fun riotous. I would love you to glance at it some time.” In that letter he mentioned that two American publishers had already turned the book down.

Wilson of course agreed to look at the manuscript, and Nabokov waited anxiously for his feedback. His fortunes had sunk yet again. Not a man given to self-pity, he described himself “in a pitiful state of destitution and debt.” Their common friend Harry Levin recalled that Wilson telephoned Nabokov in Ithaca during this period, prompting the latter to expect enthusiastic comments about his new novel. False alarm! A complicated-looking moth had flown into Wilson’s house, and he wanted Nabokov’s help in identifying it.

Wilson did read Lolita, sort of. The manuscript reached him in two black binders, and he read the first half. He didn’t feel compelled to read more. “I like it less than anything else of yours that I have read,” he wrote Nabokov, continuing:

The short story that it grew out of was interesting, but I don’t think the subject can stand this extended treatment. Nasty subjects may make fine books, but I don’t feel you have got away with this. It isn’t merely that the characters and the situation are repulsive in themselves, but that, presented on this scale, they seem quite unreal.

That was America’s leading literary tastemaker speaking ex cathedra. He must have known how desperately Nabokov wanted Lolita feedback, so he included two additional reviews in his letter: a terse, disapproving note from his ex-wife Mary McCarthy (“I thought the writing was terribly sloppy throughout”), and an elegant, short appreciation from his current wife, Elena. “The little girl seems very real and accurate and her attractiveness and seductiveness are absolutely plausible,” Elena wrote. “I don’t see why the novel should be any more shocking than all the commonplace ‘études of other unpleasant moeurs.’” She concluded: “I couldn’t put the book down and think it is very important.”

In his letter Wilson reminded his erstwhile collaborator that Doubleday had forgiven them a fifteen-hundred-dollar advance for a never-delivered overview of Russian literature, and might be willing to accept this novel in its place. He also mentioned that their friend, the Doubleday editor Jason Epstein, had just launched the Anchor series of quality paperbacks, which might want to print the Onegin project. (Nabokov called Doubleday “day-day” . . . of course.)

Epstein remembers the back-and-forth over Lolita. “I was visiting Wilson, and he handed me these two black binders, which were the manuscript for Lolita,” he recalls. “Wilson told me, ‘Vladimir doesn’t want anyone to know that he wrote this. I found it repulsive, but you won’t.’” Wilson was right. “I found it to be very amusing,” Epstein says. He tried to get the book published at Doubleday, but the house’s chief executive, Douglas Black, had spent sixty thousand dollars in legal fees defending Hecate County, and wasn’t eager to get back in the ring with the Catholic bluenoses. “I was angry that they turned it down,” Epstein says. “It was one of the reasons that I left the company.”

Lolita’s tortured publishing history has been widely documented. Stymied in the United States and desperate for cash, Nabokov allowed his European agent to sell the manuscript to Maurice Girodias’s Olympia Press in Paris, best known for publishing avant-garde manuscripts, pornography, and combinations thereof, for example, William S. Burroughs’s Naked Lunch and J. P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man. That was in 1955. In a year-end review for London’s Sunday Times, Graham Greene pronounced Lolita one of the best books of the year. Conveniently, the editor of the popular Sunday Express tabloid declared Lolita to be “the filthiest book I have ever read” and “sheer unrestrained pornography.” Almost overnight the book became an international public sensation. British customs banned importation of the Olympia edition, and then France banned publication altogether.

Well before the book crossed the Atlantic, The New York Times took favorable notice of its travails. “[Lolita] shocks because it is great art, because it tells a story in a wholly original way,” is an anonymous reader’s comment that Harvey Breit recycled into his “In and Out of Books” column. Breit noted bemusedly that his informants were comparing Nabokov to Nathanael West, Fitzgerald, Proust, and Dostoyevsky: “Not a real best-seller among them—so to hell with it.” That was in March 1956. G.P. Putnam & Sons then decided that Nabokov’s young protégée might be ready for her American debut. They went to press in August 1958, and Lolita rivaled Gone with the Wind for unprecedented sales volatility. Putnam sold one hundred thousand hardcover copies in three weeks.

Although Lolita was battling heavy weather in the Old World, the United States had moved on from the days when conservative Catholic publicists could pillory “indecent” books. Much-banned books such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, were finding their way, legally, into bookstores. The Supreme Court had recently struck down a Michigan book-banning ordinance. Ironically it was Wilson’s erstwhile friend Felix Frankfurter who opined that for Michigan to outlaw adult books that might hypothetically fall into the hands of children was “to burn the house to roast the pig.” What seemed provocative in 1946 was just another stop on America’s vicarious bed-hop in 1958. Grace Metalious had relocated Hecate County to rock-ribbed New Hampshire, selling one hundred thousand hardcover copies of her steamy best seller, Peyton Place. Furthermore, Lolita was high art; Graham Greene, Iris Murdoch, Stephen Spender, and any number of equally acculturated worthies said so.

I doubt anyone would have told Wilson this, and I doubt he would have acknowledged it, but Lolita was a far better book than Hecate County. It was better written, better plotted, and, in parts, hilarious. (“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury . . . we are not sex fiends!”) The novel laughed with itself and poked fun at itself with a gossamer irony that simply wasn’t in Wilson’s literary tool kit.

Hurricane Lolita (from Pale Fire, ll. 679–680: “It was a year of tempests, Hurricane / Lolita swept from Florida to Maine”) swept across Europe, America, and the world, changing the Nabokovs’ lives forever, and inevitably changing their relations with Edmund Wilson. Wilson acknowledged to Nabokov that the “rampancy of Lolita . . . seems to have opened the door to other wantons,” meaning that Hecate County would reappear in 1959. But it flopped, and Lolita continued to soar, over new countries and over new continents. Wilson could be forgiven for thinking: There but for the errant grace of God go I.

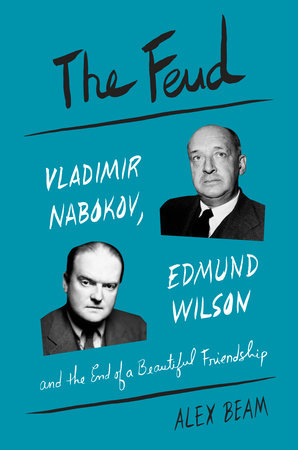

From THE FEUD: VLADIMIR NABOKOV, EDMUND WILSON, AND THE END OF A BEAUTIFUL FRIENDSHIP, courtesy Pantheon. Copyright 2016, Alex Beam.

Alex Beam

Alex Beam has been a columnist for The Boston Globe since 1987. He previously served as the Moscow bureau chief for Business Week. He is the author of three works of nonfiction: American Crucifixion, Gracefully Insane, and A Great Idea at the Time; the latter two were New York Times Notable Books. Beam has also written for The Atlantic, Slate, and Forbes/FYI. He lives in Newton, Massachusetts.