Budapest in flames. New York crumbling into the sea. Los Angeles in ruins. The Soviets had rushed in with weapons but were not shooting. Nuclear war had come and gone. He was asleep and awake and dead but alive. Stalin had returned. Hitler had returned. Our planet was to collide with another. His parents had been abducted and lobotomized, surgically enslaved machines who wouldn’t recognize him. The trains were running again—on tracks forged from bone and teeth and hair. The Martians would be merciless with our bodies, they would torture and vivisect and experiment. They would show us pieces of ourselves. Ancient beasts would slither out of the oceans and pull the entire city down into the abyss. The trains had never stopped.

It had been a deep sweat of days: newspapers, nightmares, drinks, double features, men. “You don’t look well, George,” Jack said. It was already Friday. At the studio George watched his typewriter as though it might write something by itself. How hard could it be? It didn’t take much to pass as a script, not in this town. He continued to ignore the entreaties for a sequel and instead tried formulating a treatment for the robot picture, but he could only describe the robot’s duplicitous all-American flesh in such detail that he had no choice but to take the pages home and burn them. “You should be celebrating,” Jack went on. “At the beach last night, some boys were just tormenting this poor girl, telling her the sand was teeming with radioactive spiders. That pretty soon they’d take over the whole city. You’ve really done it, George. You opened the little door in their little heads and stepped right in.” But what did movies matter in his life now? Who cared if one of his little fantasies—his bedtime stories, he said—got talked about or written up or even made money? He hadn’t wanted to think about his home country in years, and now one of the world’s great nations was out there being reborn.

“You always know just what to say, Jack.”

On the balcony, he smoked and watched the production teams build and rearrange their flimsy worlds. Wispy ropes of clouds lassoed and whipped the sun westward. Whatever ends us, he thought, will come from the sky. California had meant itself to be the end, the paradise, the refuge. But it wasn’t enough. It wouldn’t be safe. We were a planet now, no way off or out.

What was happening in Budapest had destabilized him. Three days in, they were calling it a revolution. Stalin, despite George’s nightmares, was still dead, but his haunted government had sent troops to protect the Hungarian People’s Republic from the disgusted youth and their ideas. At first, the Americans were excited—a nation was turning its back on Russia—but when they learned that the young people and their intellectuals had given a list of demands, all of which would protect workers and provide medicine to all and offer educations to anyone who wanted one, that excitement turned into betrayal. These socialists, it was said, would get what was coming to them. The people had chosen their fate.

*

Even a happy dog, an idiot dog, has a nose like a hunter’s hound. The Americans who peopled George’s life asked him for his thoughts on this “revolution.” He confessed he knew nothing, same as they—that is, only what he read in the papers. When they felt brazen enough to ask where he was from, he said as he’d always said—“Europe”—preferring its lack of commitment or association. It still worked, though he could see less of an understanding now, and in its place a flowering suspicion. Good Europe or bad Europe? He stopped reading in public places. He pretended, as Jack drove them to and from the studio, that he was too tired for the news. Which wasn’t, he told me, a hard thing to pretend. He barely slept and felt feverish, damply paranoid from morning to night and night to morning. There would have to be somewhere for him to go, and soon. He hoped never to hear communism or capitalism ever again; he only wanted, once more, a home.

The nightly movies were supposed to annihilate his brain. He went to worship and to be destroyed but instead saw juxtapositions, and he analyzed them. Theaters south of Sunset offered additional distractions, but even the cocks he sucked in men’s rooms couldn’t obliterate him. He was thinking in sentences now. In structures. It was putting itself in front of him, a wintry tree flush with fat and lazy fowl free for the shooting. He wanted to write something real, something that would be part of a conversation. He broke an old rule and drank himself stupid. It was harder to guard a secret when you felt most like yourself, when you relaxed into yourself. You never knew what you’d say after a martini, and to whom, but it was worse, he told me, to be conscious, to be thinking and thinking of what would come next, of what kind of world, if he had a say in it, could be built. It wasn’t, after all, like living in English; there were only so many people who spoke his real language and it was hard, in a moment like this, to keep yourself cut off from them, to withhold your imagination, even your wisdom, in a time of deep, dreamy need.

To paper over his long absences, he plied Jacques with gifts. He especially loved french fries, and if George showed up with a cone of them from the hamburger stand on Sycamore, even at ten o’clock at night, he could avoid an incident. It felt ridiculous and false. Whatever existed between them seemed measured in the calm between incidents; eventually, he’d have to get rid of him or leave him behind. It wasn’t something either could sustain, even if Jacques was too young to know it. Being lonely was so terrible. Someone who smiled when you mispronounced a word, or who plucked an errant eyelash from your cheek—it would weaken anyone. You’re just tired, George told himself. You can’t think clearly. You’ve no faculty for judgment. In other dreams, different dreams, he and Jacques lived in Budapest and sipped coffee on balconies. They wore long coats and visited museums and lived, simultaneously, in the mountains above Los Angeles. They walked in the clouds and swam in the ripples of the sky. “You’re burning,” Jacques said as he shook him awake. Despite his youth, Jacques understood illness; it was clear that someone had nursed him, loved him, before they’d cast him out. “Poor Georgie,” he whispered—only a pet name, but closer than anyone else in this city had come to George’s foreign, forgotten syllables.

*

That Friday, he called Madeline. She would appreciate his pain, at least if he made it exciting, exotic. Jack had left early—he hadn’t bothered to say why—and Ellman was little more than furniture. George let a little of himself out. “Let’s say,” he began, “that someone demanded you define love . . . ?”

“Christ, George,” she said. “It’s early.”

“It’s nearly five o’clock. Post meridian.”

“Is that all?”

“No one ever thinks it’s going to happen to him,” he went on. In truth, George still didn’t believe it had happened to him. He knew “love” here was fever and fervor, tangled in revolution—a young soul trapped in Hugo or Tolstoy, or some university youth with a tattered and cripplingly underlined Lukács. The politics of it, even the shape of it, had infected him with an adolescent’s passion. He wanted to stand somewhere and make a speech people would remember. But Madeline yawned aggressively whenever anyone mentioned politics. Besides, it was never a good idea, anywhere, to be too terribly specific when phone lines were involved. So he blamed his heart. “I honestly don’t know what to do with . . . her.”

“Yes you do. I’m sending a car.”

“Don’t be ridic—”

“Call her and tell her to pack for a weekend. Swimsuit optional, as always. Drinks are at six thirty, dinner at seven thirty. I’ll start getting ready now. Oh, George, this will be wonderful, thank you so much for suggesting it.” She hung up.

George looked at the receiver as it mocked him with its drone. He set it down gently, a creature that might easily anger. Ellman had the faintest grin tugging at his cheek. “You have interesting friends,” he said, then turned and winked. It was jarring, like noticing a statue or painting had moved overnight. He went on, still trying to make eye contact: “I have interesting friends, too, if you’d ever like to meet them.”

George smiled. “I’m not sure anyone I know is as interesting as all that,” he said, and excused himself and rinsed his face in the lavatory sink. Only an idiot would fall for such an obvious trap, he thought. But then what was he lately but an idiot? Strung out on nightmares and a bad chill?

Perhaps Madeline was right. Some sun, some sea. Vainly, he let his hand drape slowly down the contours of his face, the paunch under each eye that rarely, these days, went away, and the twin lines, like parting curtains, that swept away from his nose and out toward his jaw. As he’d watched Madeline do, in her vulnerable moments, he placed a finger at each of his temples and pulled up and back, only a little, and watched all those lines vanish at once. Then he let go, and frowned.

*“It’s so peaceful,” Ellman said as George returned to his chair, “without that yahoo clomping about.” If George’s desk was east on their office compass, and Ellman’s south, Jack was their North Star; no wonder, he mused, we are adrift. He ignored Ellman’s signals, whatever they were, and pictured instead Jack’s body, how the casual baring of it, the parading of it, stung like the opulence of the homes in Beverly Hills, or of citrus trees casting their fruit into the dirt. It was peaceful, George realized—like death or like growing horribly old. Jack was a movie; he made you want to feel erased.

__________________________________

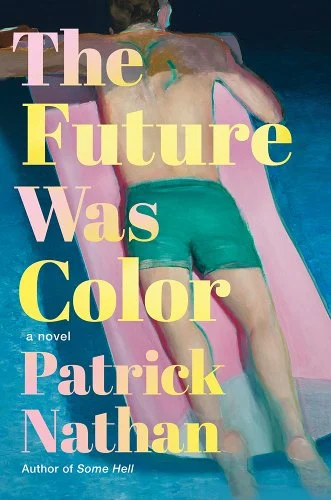

Excerpted from The Future Was Color, copyright © 2024 by Patrick Nathan. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.