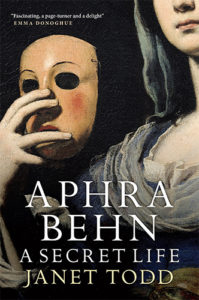

The First English Woman to Make a Living as a Writer Was Also a Spy

On Aphra Behn, Playwright and Punk-Poetess of the 17th Century

Aphra Behn was the first English woman to earn her living solely by her pen. The most prolific dramatist of her time, she was also an innovative writer of fiction and a translator of science and French romance. The novelist Virginia Woolf wrote, “All women together ought to let flowers fall on the tomb of Aphra Behn . . . For it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.” Minds and bodies. Behn was a lyrical and erotic poet, expressing a frank sexuality that addressed such subjects as male impotence, female orgasm, bisexuality and the indeterminacies of gender.

No woman would have such freedom again for many centuries. (And in our frank and feminist era Behn can still astonish with her mocking treatment of sexual and social subjects like amorphous desire, marriage and motherhood.) During the two more respectable or prudish centuries that followed her death in 1689, women were afraid of her toxic image and mostly unwilling to emulate her sexual frankness. In her day, Behn had the reputation of a respected professional writer and also of a “punk-poetess.” For a long time after her death, she was allowed only to be the second.

Beyond her successes on the stage and in fiction, Aphra Behn was a Royalist spy in the Netherlands and probably South America. She also served as a political propagandist for the courts of Charles II and his unpopular brother James II. Thus her life has to be deeply embedded in the tumultuous 17th century, in conflict-ridden England and Continental Europe and in the mismanaged slave colonies of the Americas. Her necessarily furtive activities, along with her prolific literary output of acknowledged and anonymous works, make her a lethal combination of obscurity, secrecy and staginess, an uneasy fit for any biographical narrative, speculative or factual. Aphra Behn is not so much a woman to be unmasked as an unending combination of masks and intrigue, and her work delivers different images and sometimes contradictory views.

Much is secure about her professional career as dramatist, but there’s a relative paucity of absolute facts about Aphra Behn’s personal life. Coupled both with the sly suggestions she throws out and with her wonderfully inventive method of weaving experience and fancy with historical fact, this circumstance suggests that speculation and intuition are at times appropriate modes for her biographers. People of the Restoration made mirror and distorted mirror images of themselves. Fooling and deceit were art forms. So identifications in her life story are tentative, and the characters in her “true” narratives and poems, relatives, friends and lovers, may be composite—or imaginary. I continue to see with varying degrees of clarity a “real” woman and a protean author of protean works.

*

The past 20 years of critical commentary tell me that, as an author, Aphra Behn is secure in the canon of English literature. She is taught in colleges and universities in English-speaking countries. Where Restoration drama is on the syllabus, she is there with the other great playwrights, William Wycherley and William Congreve. As author of some startling and innovative fictions, she enters as an originator or precursor of the modern English novel, along with Daniel Defoe and the trio of early women writers, Margaret Cavendish, Eliza Haywood, and Delarivier Manley. Because of its setting in Surinam, her celebrated novella Oroonoko about a princely black slave is favoured in postcolonial studies. Finally, in women’s studies courses, Behn is hailed as the first thoroughly professional woman writer, concerned with her craft, with details of publication, and with her status in the literary world.

For all this critical activity, Aphra Behn is still not as high in appreciation and recognition as I believe she deserves to be—and as I expected her to be when I began thinking about her in the heady 1970s, that decade of rediscovery when so many past women writers were allowed out of the shadows. With her craft and experimental techniques, her exciting female perspective on everything from politics to domesticity and sex, I thought her on a level with Jane Austen in literary importance. I still do. And it’s hard to imagine a more striking and adventurous life—even if a good deal of this life is and was intended to be secret!

Most of the articles and comments on Behn in the last two decades have been scholarly and subtle. They have responded to the changing fashions of the discipline of English and Cultural Studies. Second Wave Feminist criticism that brought her to greater notice in the 1960s and 1970s has given way to other “Waves” much concerned with the performative and with amorphous and polymorphous desire, while the emphasis in postcolonial studies, that other growth area within the discipline, is still overwhelmingly concerned with race and ethnicity. Aphra Behn as writer of sexually explicit poems and portrayer of England’s early colonies has much to say in both areas of study.

Recent scholarship has concerned Behn as dramatist and poet. It throws new light on her stagecraft, her shifting and often prominent position in the theatrical marketplace, as well as on her complex interactions with male colleagues and competitors such as John Dryden and Thomas Shadwell. In her theatrical dedications Behn uses flattery in ways that both amuse and dismay present critics and, in her plays, she portrays rakes and whores with the kind of ambiguity that can be disturbing—as well as funny. Behn was fascinated by rank, by the notion of nobility, its honor, and the manifold ways in which it could be dishonored. She returned to the topic over and over again in her drama, investigating the allure and vulnerabilities of personal and political authority. Critics have applauded her lively enthusiasm for sexual games and her irreverence about the masculinity that dominated the age and which she expresses so well in her plays and in her frank and risqué poems. If her treatment of sex astonishes readers less than it did a century ago, Behn can still shock when she handles subjects such as rape and the seductions of power. In many areas of gender relationships, then, her drama, fiction and poetry are still capable of destabilizing our own assumptions. So, too, can her utopian moral and political schemes, where desire and reality coalesce or clash, and where the body is left to subvert the mind.

However interesting and disturbing so many of her works can appear, overwhelmingly comment has settled on a single one, Oroonoko. This is usually delivered not in its historical or literary context but in terms of modern ideas of race, ethnicity and gender. Sometimes the novella is coupled with Behn’s posthumously produced play, her “American” work, The Widdow Ranter, set in the English colony of Virginia. Both novella and drama excite clashing interpretations.

For some contemporary readers The Widdow Ranter seems to advocate republican values against a stuffy, hierarchical and anachronistic world order that cannot easily adapt to a changed environment; the play discovers a superior cultural space that expresses America and a non-European future of freedom. For others, the work is staunchly and overtly monarchical, revealing the chaos of democracy that emerges when the “people” are given power and allowed to decide; we may relish the Falstaffian carnival element of the play, but the whole remains a portrait of misrule in a disordered colony requiring noble English governance to restore order and prosperity.

“Behn was fascinated by rank, by the notion of nobility, its honor, and the manifold ways in which it could be dishonored.”

Oroonoko provokes even greater interpretative divisions, especially in its depiction of slavery. This is an overwhelming interest of our own age and, inevitably, as with sex and gender, we look through our modern assumptions at a work written before the secure establishment of the dreadful trade of African and American slavery and when slaves included Englishmen caught by the French and Turks, as well as famous classical slaves like Aesop. Some readers find Oroonoko a roundly aristocratic text stressing nobility and rank beyond anything else. Nobility for Behn can be found in anyone, regardless of the color of his or her skin; conversely, the ignoble of whatever ethnicity deserve slavery. Ignoring the hero’s own involvement in the trade in slaves, other readers see an abolitionist work, and they apply to this fiction of fluidity in types and ethnic groups such modern terms as “miscegenation” and “imperialism.” When Oroonoko and The Widdow Ranter are brought together, critics are more in agreement: for Behn may appear to combine humanism with an enthusiasm for noble honor, a comic understanding of life with a less characteristic tragic one.

If Aphra Behn’s depiction of gender and race can be assimilated to our modern ideas or at least celebrated for its difference, her politics when separated from the moral and social results of Restoration government often remain troublesome. Many critics worry over the apparent conflict between her feminist understanding and her staunch Tory royalist stance. Recent work has looked at her attitude to the various plots of the age, the Popish Plot and the Meal-Tub Plot and her mockery of false rulers like the would-be king and rebel, the Duke of Monmouth. The work sheds light on some of the difficulties in interpretation.

In her plays and stories readers have found conflicting political messages. Some see occasional critiques of the royal brothers Charles II and James II, others simply an exaggerated loyalty against apparent odds and the currents of history. Perhaps, as contemporary readers, we find splits between desire and hierarchy, between women and dominating monarchy, and between hedonism and loyalty where she and her age found no necessary distinctions. Behn lived through a time of immense national upheaval and we may be wrong to look for consistency. The Vicar of Bray is not the only person who had to move with changes in regimes.

Her literary milieu was quite different from our own. All educated men and many women were familiar with the classics and, although as a woman Behn would have been denied a university education, she reveals herself well aware of the literary culture of her time. Undoubtedly when reading her we miss many allusions that her original readers and auditors would have caught, both from the Greek and Roman authors and from her contemporaries: the dramatists, poets and romance-writers. Aesop’s Fables, which Behn rendered into English verse, may leach into her narratives where animals may grow characteristics and show unstable identities. The romantic tales that filled the minds of her readers may enter a work like The Fair Jilt far more than we now expect. What we might see as autobiographical like “Love-Letters to a Gentleman” may indeed reveal something of Behn’s life and loves but also represent a pastiche of the fictional letters so popular at the time. And in this case, since they were published after her death by a notoriously unscrupulous publisher, there is always the possibility that they may be forgeries, so useful and lucrative was the name of the notorious and amorous Mrs Behn.

Claudine Van Hensbergen underlines this possibility when she reiterates the problematic nature of seeing the letters as Behn’s subjective thoughts. After all, they were written in a period fascinated by the Portuguese Letters, supposed to have come from the pen of a despairing nun rather than, as is now thought, a male French diplomat. The Behn letters may be strategic constructions after her death to help make her an amorous bankable heroine, or, of course, Behn may be using a conventional form to express something both literary and experienced, distraught and manufactured. The many connections between the letters and Behn’s secure works can reveal a hard-working ventriloquist or Behn often writing self-referentially.

Like so many authors of the age, Aphra Behn claimed much of her work was true. It was fact or history. In reality it might well have been all fiction or fact mixed with fiction. This is especially so of the writings based on her presumed periods abroad in Surinam and the Low Countries when she was a young woman in the 1660s. Any new information about this time is welcome indeed. One of my moments of greatest archival excitement in writing my biography of her in the 1990s was when, following leads from Maureen Duffy and Mary Ann O’Donnell, I found in the Cathedral records of Antwerp the statement of the wedding of the historical original of the protagonists from The Fair Jilt: Francois Louis Tarquini and Maria Theresia Van Mechelen. Later I opened the roll of dusty and decaying testimonies of the defendants and plaintiffs in the legal cases that followed. I worked with difficulty, having only a Dutch–English dictionary for help. So it is a pleasure to find Dutch and Belgian scholars now fleshing out and modifying this historical background and providing more of the detail of the events on which Aphra Behn may well have drawn.

My other exciting moment was also archival, seeing the proof that William Scot, the agent she sought to bring back into the English fold and whom, I speculated, she had assumed was in love with her, was in reality a triple agent—at least. Probably further material will emerge as Continental readers and scholars become more interested in the English émigrés of the Restoration and in Aphra Behn herself. So far nothing much alters the broad outline of what I wrote in the biography. But who knows what may yet be discovered? It was the business of spies to hide themselves.

__________________________________

Adapted from the introduction to Aphra Behn: A Secret Life. Used with permission of Fentum Press. Copyright © 2017 by Janet Todd.