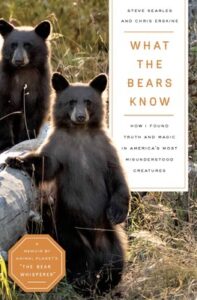

The Bear Whisperer Lays Out the Profound Impact of Wildfires on Southern California's Black Bear Population

"I am surrounded by these bears that have been my life’s work. Bears, bears, everywhere, lost and in need."

Inch by inch, hour by hour, the flames are bearing down on us. We are a town under siege.

Through the same canyons that usually funnel wind, rain, and snow to Mammoth Lakes, comes a wall of fire unlike anything anyone has ever seen. Plush and super dry, the forest floor may as well be laced with lighter fluid.

The epic high winds feed a fire so hot it sterilizes entire swaths of wilderness. It is the potential apocalypse of all I hold dear—lakes, mountains, trees, animals, my house, my neighbors, my son.

My town, Mammoth Lakes, is almost a parable. Everything except locusts has hit the Sierra Nevada region since I moved here: floods, droughts, blizzards, avalanches, quakes, and, most destructive of all, this ferocious wildfire.

Thick, acrid ash falls during this 2020 fire. From this ornery orange sky, dregs of poison oak smear our faces, plug our tear ducts and noses. The next day, it’s the manzanita that burns, a scruffy plant used in folk medicine. In short time, we become connoisseurs of our burning forests. We breathe it.

We eat it warm. It is as if someone has opened a giant urn. The ash isn’t just wood ash and leaves; it is forest life, scorched.

We can feel it lumpy under our eyelids.

Nothing is surviving. Tree roots are burning underground. The nests of bald eagles, often reused for years, are scattered in this stinging ash fall, which includes the remains of tens of thousands of fleeing forest creatures. How can I be so sure of this mass cremation? Because the mountain town of Mammoth Lakes, with its beltways of creeks and golf courses, its sprinkler systems and its pools, would have been their only escape route, their interstate out of the savage Creek Fire, as it is named. There is no Pixar parade of fleeing animals, though. They simply vanish, the deer running till their lungs explode, followed by bobcat, cougar, racoons, porcupines, owls, skunks, moths, chipmunks, even the worms that churn and condition the soil.

The quivering aspen and the pines—lodgepole, Jeffrey, pinyon—all gone. The forest floor is wiped out—manzanita, buckwheat, bitterbrush, goldenrod, black oak, mule ear, and ferns. The nectar in the flowers, the wings of butterflies, sterilized and possibly gone for a generation or more, all the seeds cooked, along with hopes of a rapid and glorious recovery. We are witnessing the death of an ecosystem, an entire food chain falling on us now in an awful gray and black confetti.

By now, Americans know all about wildfires—we’ve been living with them and hearing of them for years. What makes the Creek Fire different, what raises the stakes, is that this is an especially magical piece of the planet, a carousel of national parks and wilderness areas. All appear at risk: the Ansel Adams Wilderness, the John Muir Wilderness, Yosemite National Park. The vaunted Pacific Crest Trail runs through Reds Meadow. Long-distance hikers heading to Canada will lay up for five or six days here, have a fling, play the flute, pound a burger, drink an ice-cold beer.

When outsiders ask me if the Sierra Nevada has ample wildlife, I wait a beat, then answer in my Sam Elliott growl: “It’s Jurassic Park.”

In essence, this is a sanctuary city for all manner of wildlife, a place that attracts and protects its forest creatures. After forty-four years up here, I’ve learned to read these woods. I can tell the time of year by the spots on the fawns wading a mountain creek. I can read the shadows, the sunlight, the chatter of the geese as if they are the pages of a kitchen calendar.

I am this town’s wildlife officer, known through countless encounters as the go-to guy when wildlife is in distress, particularly these misunderstood, quarter-ton outcasts.

This is spectacular terrain, fierce and fragile, among the loveliest regions on Earth. The spirits of John Muir and Ansel Adams still roar through these tall granite canyons. Take particular note of the veritable wind tunnel that delivers rain, ocean winds, and—starting around Halloween—epic snows. By late December, we’re the North Pole—so much snow that we hot-wax our shovels, as you would a set of skis. In winter, the air is especially fresh, as if it’s just been born.

Indeed, this is California’s Switzerland, well-muscled, almost brutally snowy. Come January, the icicles alone—big as tree trunks—could kill you. All winter long, they cleave off the roofs of cabins and hotels, another lethal reminder that winter up here is a form of war.

Most times, this tunnel of winds and wet storms is a superhighway of much-needed moisture and snow for Mammoth Lakes, a tourist town five hours north of Los Angeles. In winter, it coats the world-class ski runs and halfpipes where gold medalists such as Shaun White and Chloe Kim train. In summer, it feeds the crystalline rivers and lakes popular with fishermen. The hurricane-force winds, frequently topping one hundred miles per hour, ruffle these mountains a bit, adding movement to the painterly landscape and knocking loose the seeds that will be the next generation of pine trees, gusts that scatter the bees, the pollen, the fuzz of the wildflowers.

When the winds hit one hundred miles per hour in Florida, it’s the lead story on CNN, the talk of Twitter. Here, no one says a thing. We go on with our lives and head out to the hardware store—just another day in this frosty paradise.

Mammoth Lakes is also a vital headwater. A snowflake that falls atop a black-diamond ski run might end up in someone’s iced tea in Pasadena. It might come off the mountain on the tip of someone’s snowboard, melt into a parking lot storm drain, feed a gushing creek on the way to reservoirs that flow into the canals that loop all the way to Southern California.

The Eastern Sierra is to drinking water what Wisconsin is to cheese. We are the kitchen faucet for millions of humans, dogs, cats, canaries, horses. Obviously, this is a very abundant place, the glint of sun coming through those massive icicles, across a snowy tree branch, over the cross-country trails, the waterfalls, the On Golden Pond–caliber lakes filled with rainbow trout. Sometimes it feels almost greedy, this bounty, just miles away from the stubble of the relatively dormant desert. In Mammoth, this lush and popular pocket of the Eastern Sierra, we have too much of everything: water, snow, coyotes, tourists, cheeseburgers, putting greens, ski shops.

Most notably, perhaps, bears.

The bears are where I come in.

Over three decades, I have been the bears’ gruff camp director. As the town’s wildlife specialist, reporting to the chief of police, I have been responsible for all the black bears that decided, among other things, that a schoolyard is a nice place for a nap. Or that a luxury hotel lobby is a convenient place to grab some calamari. Or that someone’s Range Rover still smelled of the peanut butter sandwiches the kids left half-eaten under a seat. To a bear, that’s bait. Hey, why not punch out a window and climb inside, tear up the seats, set off the air bags, gnaw the expensive leather on the steering wheel? Yum.

I was the one-man SWAT team that responded when any of that happened. If you dialed 9-1-1 and shouted BEAR!, I was the ponytailed first responder, roaring up in my white pickup and getting out with my trademark orange shotgun.

Known as the Bear Whisperer, I shooed and snarled at the five-hundred-pound trespassers, cowboy-cussed them, even shot them with nonlethal rubber balls to get them out of harm’s way, off highways, and out of hot tubs and parking garages.

My career was crazy and remarkable. Somehow, I still have both arms, both legs. In fact, in all the years of crawling into bear dens to study their sleep habits, to watch them birth their babies, in all the years of confronting bears nose to nose in culverts and cabins, in trapezing lost cubs out of tall trees, I haven’t suffered a single scratch.

Yet, in the late summer of 2020, this incredible life, this extraordinary stretch of bear magic, seems to have run its course.

Only the bears—the kings of the forest—manage to make it out of this firebox. In Mammoth Lakes, they begin showing up by the dozens, parched, and frightened beyond measure. It is a California black bear’s nature to do as little as possible, to conserve body mass. Bears are constant eaters, gorging themselves with seeds, wasp larvae, grasses—the occasional cheeseburger—to survive long winters snoozing in their dens.

So, the bears haven’t panicked the way the other animals have, haven’t run themselves to exhaustion. They stay only as far in front of the fire as absolutely necessary.

Now here they are, sooty and disoriented, the newcomers clashing with the bears that already reside here. It is as if two conventions have come to town, when we only have the space for one.

You and I, we use our noses to keep our glasses on, or to sniff an occasional IPA. The bears’ noses are their sensory command centers. Their range can be measured in miles, their snouts thousands of a times more powerful than ours. They use them to sniff out food, to anticipate changes in the weather and the seasons, determine where the fresh water is, maybe a colony of bees, or where someone left some shrimp shells in the trash. They use them for romance; they use them to know when it’s time to climb into their dens for five months when it snows.

In the normal course of my work, I might see eleven bears on a busy fall day, when they’re preparing to go into their dens for winter. Now there are at least three dozen in our four-square-mile town. At least, that is how many I’m able to count. There could be twice as many here, the others hiding in the shadows, under decks, and behind the drapes of empty cabins. Generally, bears don’t like the limelight. Like me, they prefer to exist in the margins.

With their snouts caked in fire ash, the fleeing bears are essentially blind. They can’t source food, or sense enemies or territorial boundaries. Their lungs are parched, their kidneys starved for replenishment. At my urging, hundreds of residents leave five-gallon buckets of drinking water on their porches at night; the water is gone by morning. Inexplicably, at least to me, authorities are telling residents not to leave out water, saying animals will develop a dependency. Instead, they should rely on streams and lakes miles away.

I sit on my porch in the center of the village, at the cabin that had been my longtime home, and watch the bears’ tragic migration. It probably hits me harder than most.

For I am this town’s wildlife officer, known through countless encounters as the go-to guy when wildlife is in distress, particularly these misunderstood, quarter-ton outcasts.

I know very well that grizzly bears, shot to extinction in California, are alpha predators; they’ll eat the tire off your truck. By comparison, all a California black bear wants to do is mow your lawn. They are the tie-dyed hippies of the bear kingdom.

Still, they get into more mischief than you’d hope. They learn faster than us, good or bad—where to find free food and lodging, all the life basics, even where to find a fridge full of cold cuts and beer.

Since the late 1990s, I have chased them out of the grocery stores, the condos, the tourists’ big SUVs. Bears have been in so many homes, often more than once, that I’ve lost count. Certain parts of town are almost a wildlife park. Everyone has my cell number (937-BEAR) in their phones.

Across the decades, I have tied myself financially and emotionally to these bears.

Now they need me more than ever. But my career has just come to a sudden, dramatic end. Covid has descended on Mammoth, just as it has on the rest of the world, triggering fear, confusion, and the kinds of heated debates that end friendships: During a pandemic, should a tourist town welcome outsiders, hoping the wilderness will be safe and restorative? Or should it hide and hunker down like everyone else?

There is a showdown over that, everyone panicky and in each other’s faces, including me, a longtime resident with a few valid opinions.

As if all that isn’t enough, the largest wildfire in California to date is now on the doorstep of my cherished little town, threatening to eat it whole, causing this mass migration of bears.

Now, you should know that I’m six-foot-five and noisy as a chainsaw, rough as ship rope. I’m gnarly, not easily spooked. I even look like a bear, more handsome than some, less than others.

I’ve thrived in this demanding region of lethal winters and fiery summers for almost half a century. I can fix anything, hammer together hotels, race a bike, chase a raccoon out from under your favorite pillow after he’s shredded your couch while digging for stale popcorn.

Indeed, I’ve prepared my entire life for 9-1-1 moments like this one. Till now, I’ve always risen to the occasion, stood up against tough guys and rogue bears in near-impossible standoffs and on a popular reality show that reached the far corners of the planet.

Yet, here I am after the job loss, at a personal low point, so inconsolable I can barely breathe. The hopelessness of the situation is crushing me.

I am surrounded by these bears that have been my life’s work. Bears, bears, everywhere, lost and in need.

To me, their ghostly presence is perhaps the most surreal element of all.

___________________________

Excerpted from What the Bears Know by Steve Searles and Chris Erskine. Copyright © 2023. Available from Pegasus Books.

Steve Searles and Chris Erskine

Steve Searles is a self-taught bear expert who’s been working with the animals for nearly three decades. Since 1996, he has been the wildlife specialist for the ski town of Mammoth Lakes, Calif., where he developed a global reputation for his novel approaches to keeping residents—and the bears—safe. Steve founded the town’s “Don’t Feed Our Bears” program and helped formulate Yosemite National Park’s initial bear program. In 2010, he was the topic of the reality show “The Bear Whisperer” on Animal Planet. He is a native of Orange County, Calif. Chris Erskine is a nationally known columnist, with most of his work appearing in the Los Angeles Times and distributed to 600 papers nationwide. As an editor there, he was part of two Pulitzer Prize-winning teams. He is best known to readers for his weekly pieces on life in suburban Los Angeles. This is his fifth book. He is a native of Chicago and now lives in Los Angeles.