Violet was the first sister to reach any level of fame. And it wasn’t just because she was the oldest. It was because at a young age, her talent had become obvious—everyone saw it, from schoolteachers to classmates to strangers at the mall to Roxanna. Roxanna, who lived for nineties nostalgia, especially via fashion sites on Instagram and style-influencer TikTok, was always the one hoarding old fashion magazines she would find on eBay. She would cut out photos of all-American cover girls Niki and Krissy Taylor and insist the two girls playact at being them. When Violet finally gently told Roxanna that in that scenario she, as the younger one, would be Krissy—the one who died a very tragic premature death—Roxanna transformed her momentary fluster into an exaggerated groan. So basic. Who would think to bring that up when you could instead be captivated by the tube tops and the cutoffs and the forever-wet hair and the bronze body shimmer and the perfect pearls of white teeth? She used Violet’s vibe-killing as proof of a simple-mindedness that was yet another great reason for her to consider modeling.

It was not an obvious sell to Violet. She was reserved. As the oldest, she felt some responsibility over the others, especially when Homa was checking out, in her deep depressive funks, sometimes for days at a time. Violet had looked after her sisters for as long as she could remember—she had been the one to direct the family’s team of housekeepers and nannies, sending them off with lists and reporting back to her parents on their progress.

Everyone knew Violet was the favorite. Violet, with her near-mythic beauty—she had never, not even for a fraction of a season, known an awkward phase. Violet, with her soft voice that had the feel of cotton candy and whipped honey and shredded silk. Violet, who was the Persian rose, everyone agreed, like the ingenue of a classical Persian miniature tableau, with her huge black eyes and long, silky black hair, always giving a bit of Persian princess dipped in a Ferdowsi goddess mood. Violet, the surrogate mother; Violet, the first daughter; Violet, the soft and loving and sweet heroine of a better story.

Sweet! Diabetic-coma sweet, Roxanna would snicker, because of course Violet had to have a flaw or at least an Achilles’ heel. Roxanna loved to play up her spidery frame and deep distrust of everything edible against her sister’s food anxieties. What marred Violet’s perfect record, after all, was something as American as it was Persian: Violet was addicted to sugar.

Violet’s palate ran sweet only. And so for most of her life—Homa really could not remember a time when this was not the case, her milk formula even requiring date syrup to be tolerable for her as an infant—Violet had been hooked on sweets. This was no exaggeration and a source of great wonder to everyone. How did Violet survive on sweets alone?

A typical day of food consumption for Violet would be a breakfast of sugary frosted cereal with strawberry milk, a handful of Cadbury Creme Eggs as a snack, a large caramel iced coffee with extra vanilla syrup, cinnamon bagel with pineapple cream cheese drizzled with orange blossom syrup for lunch, a large chai coffee with extra almond syrup, half a pint of peppermint ice cream with coconut-cream topping, a handful of Red Vines or Twizzlers, sweet grits with candied yams and honey-glazed coconut shrimp for dinner, some variety of pie for dessert, Jordan almonds or Junior Mints as a final dessert. Roxanna would watch her in awe; Roxanna, who was likely naturally thin, though no one could be sure, since she had been rabidly dieting since she was a toddler; Roxanna, whose diet was carrot and celery sticks dipped in soy sauce and bowls of iceberg lettuce with a few splashes of apple cider vinegar and cayenne pepper. If Roxanna was not “very underweight” on the BMI chart, she did not feel herself, she would argue; her thinness was a mindset, she argued, a crocheted Kate Moss–ism nothing tastes as good as skinny feels banner hovering in black silk over her vanity.

Violet wasn’t one to gain weight easily anyway, though in recent months, she had noticed her curves announcing themselves rather insistently. She began to wonder if Haylee’s warnings that “things will catch up with you, Vivi” were finally coming true. Haylee was unabashedly orthorexic, the family’s home gym entirely her labor of love, full of Pilates gear, weights, yoga mats, plus a steam room and a sauna. Violet’s agent had mentioned that plus-size modeling was becoming a promising new option for a lot of models, as beauty standards were shifting and influencers were suddenly being applauded for bravely showing cellulite and stomach rolls. The agency sent these reminders to Violet because they were well aware of her eating habits—on set, her agent had gone as far as to call it special needs, her manager explaining that she required sweets for energy. The usual spreads of hummus and vegetables would just not do; Violet needed milkshakes, cupcakes, sour candy, chocolate bark, gummy animals.

Of course it concerned those around her, but it also amused and delighted them. The world loves nothing more than a thin, beautiful woman who eats with abandon, someone had to have said. And so Violet, in having a dessert-only diet, was doing what few ever entertained—it seemed nearly impossible to survive this way. But she did, and there were no sugar highs and crashes, no mania or dips, just Violet serene, and in fact as sweet as the foods she consumed.

It disgusted Roxanna sometimes, though other times she felt she was living vicariously through her. Roxanna wasn’t sure she had ever consumed a candy bar in her entire life, only recalling a Hershey’s Kiss or two at the holidays or on Valentine’s Day, perhaps. She had embarked on her first diet when she was four. Though Violet was known as one of the better-adjusted sisters if not the best, people tended to blame her addiction on isolation. She had been homeschooled for most of her student life, with a few years of jumping back in just to jump back out. She had always felt too introverted to participate in normal school but it wasn’t the usual shyness; she was extraordinarily beautiful from the moment she was born, which for any K–12 kid spells constant bullying, and she needed only a season of kindergarten to spark the envy of every three-and-a-half-foot little girl around her. She grew out of her extreme introversion but not out of her need to have time to herself, to sequester and recharge, which required she be in her bedroom as often as possible—her bedroom all roses and marble accents and pink vintage lace and lilac scents, whereas Roxanna’s was minimal gold-and-black marble, smelling like the sort of exclusive boutique you’d find in Paris, aggressive and sexy, what Roxanna hoped gave off power vibes. The soft femininity and floral serenity of Violet’s space revolted her—plus, the smell gave off powdered-sugar clouds and she worried that just breathing in there would make her gain weight. A trip to the mall as a teenager changed Violet’s life. Of course it happened in the food court. Of all the clichés, the model being discovered at the mall is just so, like, nineties at best, Roxanna said, driving a spike into her model sister’s enchanting origin story. Violet had found peace sitting in the food court sipping on a root beer float, slicing into a cinnamon pretzel, and trying to very slowly pick at her bag of mostly Swedish Fish and Sour Patch Kids and Smarties. A scout had brazenly taken the empty seat opposite her, her eyes locked on Violet’s, and had struck up an innocent conversation. She had a thick European accent, and Violet assumed she was a tourist looking for directions, but after a few minutes of uncomfortable small talk, the Dutch woman in the navy blazer took a card out from her breast pocket and pushed it toward Violet with two nude stiletto-manicured fingers. Violet absently rested her root beer float on it like it was a coaster, smiled, and nodded.

“Thanks?” she had said politely.

“Young girl, do you know what this is about?” the scout said in a hissy villain tone, which mostly came from amusement over Violet’s obliviousness. Young women usually shrieked from excitement at the prospect of this dream opportunity. “Where are your parents?” she asked.

Violet shyly shook her head.

The scout looked so frustrated. “This is the real thing, girl. I think you have what it takes. No promises, but call us up and make an appointment. I could be wrong, but I think I see something special in you—just not sure of your attitude.”

Violet had looked at the card with the slight head tilt of a lapdog when it all finally computed for her. “Oh my goodness. Modeling? Wow.” She was about to pull out her phone and suggest the scout take a look at her sister’s Instagram when it really hit her. This could really be a path for her. The kind of path that Al encouraged each of the sisters to find, even when they were small.

“Ulrika,” Violet sounded out. “Thank you.”

The scout moved her eyes to Violet’s snack spread. “Just don’t tell me you have that problem,” she said, waving her hand at the mess of sugary forbiddens.

“What problem?” This was a modest spread compared to her usual.

Ulrika grew flustered. She had forgotten the name for the disease, but it was a common one among her girls. She waved her hand at the snacks again and then her long pointer finger hovered at her mouth, while her body rippled in an exaggerated heave.

Head tilt from Violet.

Ulrika waved her hand at the bathroom across from them and made vomiting sounds, a bit too loudly, until Violet seemed to get it.

“Oh, barf. Barf ?”

Violet was sixteen, a young sixteen. And because she was homeschooled, she had not been around too many kids her age. Bulimia was not yet in her vocabulary.

The scout assumed Violet did not want to admit her problem, so she let it go and decided to just forget what she saw at this young potential’s table. Instead she focused on Violet, a tall girl, with curves, her heavily moisturized honey-brown skin, iridescent lavender tube top and pink gingham pencil skirt, and silky black hair French-braided down her back. She looked like she had walked off a teen-romance movie set, a universal love interest.

The only meaningful question she had asked Violet was her age—she would need parental consent—and the rest of the time, the agent talked. Violet had taken in what she could, but a combination of her shyness and queasiness had made it all feel like a dream. The next day, not believing that what had happened was real, she let Roxanna finally make the call for her.

“Yes, Violet M-I-L-A-N-I,” Roxanna said over the phone, with a thumbs-up sign to Violet, who sat next to her trying to make out Ulrika’s voice on the other end. “I am the mall girl you spoke to. And I am so thrilled you found me ”

She went on and on, and plans were made. “I have a sister you might want to meet too,” Roxanna added, winking at Violet. “She’s a bit younger, but she was made for this stuff. She’s, like, a lot thinner than me too, much more into fashion—should I bring her?” The scout reluctantly agreed, and a week later, Homa was driving her two oldest daughters to a modeling agency appointment.

Violet wore a misleadingly simple calico dress with a sweet-heart cut—a vintage Betsey Johnson—with gold Vivienne Westwood Mary Janes that belonged to Roxanna. Roxanna had done her sister’s hair too, which was sprayed stiff and swept to one side. She had done Violet’s makeup according to a tutorial she saw on YouTube for “unicorn girls,” all blurry pastels and iridescent shimmer with muted rainbow tones, confection references, and an all-around manic-pixie cloudscape ambience. Violet felt as uncomfortable as ever, but when she saw her thirteen-year-old sister in a medley of mismatching but gutsy metallics—Daisy Dukes, a halter top, a choker, a beret, and platform clogs, all in a haze of silver, gold, and bronze—she felt relieved. Maybe the attention would fall on Roxanna instead of her. The entire car ride, as Homa glumly listened to Roxanna’s directions, Violet silently popped chocolate-covered espresso beans and prayed for the best.

The interview had been more like a casting—or so she thought, as she barely understood what castings or even interviews were like in the first place. Ulrika and two of her coworkers looked Violet up and down while Homa and Roxanna waited in the adjacent reception area. Roxanna had tried to come in with Violet, but Ulrika stopped her.

“I am the little sister she mentioned on the phone.” Roxanna flashed a huge smile. “The thinner, fashionier one. I wasn’t at the mall that day but I’m here now!”

Ulrika had looked at her, this strange, glittering girl who looked made of coins.

“We will call you if we need you,” Ulrika muttered. “Violet’s mom, can you come in?”

A half hour later, when Violet walked outside, her face flushed, her hands wrapped around her body as if she had been violated, Roxanna assumed it was all over. Violet looked sad, a unicorn with no chance of horn, and so she thought it was best not to rub it in. Roxanna put her arm around her sister to console her.

By the time they pulled into the long driveway at home, Violet knew she had to say something.

“Well,” she said as the Audi doors declared themselves unlocked and she stepped into the almost annoyingly perfect Southern California midday sun, “I guess I am a model now, whatever that means.”

__________________________________

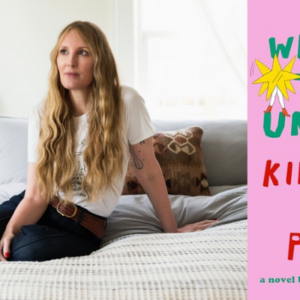

From Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour. Used with permission of the publisher, Pantheon. Copyright © 2024 by Porochista Khakpour.