When the paperwork’s done, I hitch a ride to Klak in the bed of a Chevy pickup so rusty I can see the dirt road passing through the holes between my feet. I watch the dust rising and occasional bits of trash zip by. The Chevy hits a bump and a baseball-sized piece of the truck bed falls into the frame and is gone. I watch it shrink on the road behind us. I slap the side of the truck, ask to be let out. I say, “I think your truck’s rusting out.”

The guy says, “No fucking shit,” and drives off, spitting gravel at me.

Klak’s got one processor other than ours, Neptune. There’s about five hundred workers glazing fillets and canning B-Grade salmon like they used to do in the old days. Neptune pays the same as us, smells worse, and their bunkhouses are so small you share a bed with two other workers, sleeping in shifts. The fish that don’t make the cut at our plant or Neptune go to the fishmeal plant that hires mostly locals, Native and white, at twelve bucks an hour. People are always comparing bad smells to farts, but the place where they bake the fishmeal really, truly smells like farts. It smells like nothing other than farts.

It somehow smells like every kind of fart at once, but only farts. Nothing else. It’s so bad they agreed with the town of Klak to only bake the fishmeal at night.

Past Neptune is the police station, just an outpost of the bigger station thirteen miles down the road in Paulson. It’s about the size of a shipping container and the heavy steel door is locked. A sign says, CALL 911 FOR EMERGENCIES. Is this an emergency? My dad was dead for a week before I even found out. I can see past the bluffs from here. The bone’s probably under a hundred feet of water by now. And my phone doesn’t work here. I scribble a note on the back of a ruined employment form from earlier.

EMPLOYEE AT KLAK FANCY SALMON FOUND WEIRD BONE ON BEACH AT LOW TIDE NEAR HALIBUT POINT TANGLED IN FISHING NET THOUGHT MAYBE HUMAN LEG IDK PROBABLY NOTHING THOUGHT U SHOULD KNOW LEFT BONE IN FLATS LIKE AN IDIOT.

I tuck the note under the door and head to the Black Dog. Inside it’s like a beachcomber’s coffin, the usual coastal shit on the plywood walls. On the wall behind the bar are about a hundred portraits of boat wrecks. Boats upside-down. Boats teetering on rocks. Two boats on fire, and one small gillnetter partially sunk after two sea lions climbed aboard to fuck. With the fishermen heading out, the Black Dog’s empty.

Just a Native guy on break from the fishmeal plant, smelling worse than my hands, eating chicken tenders and drinking Pepsi. At the other end of the bar, an old, sunburned drunk is swaying with a hand-rolled cigarette in his mouth. There’s no bartender.

He turns to me and stares. “How’re your dogs?” “I don’t have any dogs.”

“Thought you were somebody else.” “Is there a bartender?”

He yells, “bartender!” three times in a row.

Fishmeal says that the bartender had to run out for cigarettes. I lean over the bar and grab a mug.

“Not sure if I’d do that.”

I pour myself one and drink until the foam blots the tip of my nose. The drunk has a big mole on his forehead and when he squints the mole looks like it might take off and orbit his face. He asks me where I’m from.

“Pennsylvania.”

“I knew a guy from West Virginia. Linus Smith.” I lean over the bar to refill my mug.

“That old pigfucker, Linus,” he says. He pulls back his vest and before I can even see it, the glint says gun. “He’s the reason I keep this on me.”

I say what you’re supposed to say. “Well that sounds like a story.”

His name is Bill and in the mid-1970s he was living in the Alaskan interior and working as a hunting guide in the fall and a trapper in the winter. Linus lived in an A-frame in Talkeetna and was known for being generally full of shit. They knew each other because Bill’s sister Jeanine and Linus had dated. One time Bill lent Linus his car and got it back wrecked with a note for Bill that read, “Got u some meat.” There were two moose haunches lying in trash bags in the back seat. To say thanks, Bill kicked in the door to Linus’s cabin, blew a few holes in the roof, and stole his good boots.

Bill stares forward as he talks. It’s hard to tell if he knows that he’s talking to a flesh and blood person. I pull myself another beer. I start to smell the bone on my hands again. Sometimes when I drink, things end up really weird.

“Listen,” Bill says, and the mole starts bouncing from one side of his face to the other. That summer, Bill’s sister Jeanine sent a letter, telling him that Linus was in Minnesota and the two of them were back together. The handwriting seemed off. He called her up. Jeanine couldn’t be reached and nobody knew why. Bill flew to Minneapolis. His brother picked him up. It was snowing wet stick-to-your-eyelashes flakes and they drove to the town where Jeanine and Linus were supposedly living. They found the trailer where they lived and peeked in the window and saw Jeanine in the trailer’s back bedroom with the door closed and bunch of dirty plates and dishes stacked around her. Her arm was in a sling.

Bill knocked on the door and Linus cracked it, looking strung out. Bill said he wasn’t there to get into no kind of argument and lifted his palms upward like he was trying to catch the snow. Bill said that they were looking for Jeanine because their mother was sick. Linus said he hadn’t seen her in a few days after they’d gotten into an argument. Bill produced a pocket bottle and swigged and Linus swigged and swigged again. Bill pretended to gulp while tonguing the bottle closed. He handed it back to Linus and told him he could polish it off. Linus wouldn’t let him in the house.

“Well,” Bill told him. “I better find my sister.” He took a couple of steps off the porch and stopped. “Do you want to come along and help me check the bars?”

When Linus stepped from the door, Bill’s brother cracked him upside his head with an axe handle then proceeded to beat him across the back with it. Bill also took a turn. They tied him to the sink and left with their sister, taking three hundred dollars in cash as compensation for pain and suffering.

“Not three years later,” Bill tells me, “and that man went to prison for murdering a guy with lawn darts.”

“Horseshoes,” Fishmeal interjects. “You told me he beat a man to death with some horseshoes over a game of horseshoes.” “No, he killed him with lawn darts over a game of lawn darts.”

They start to bicker, and Fishmeal throws his hands up and heads for the bathroom. I look at those two sea lions fucking and the broken boat next to them and I think about how my dad could’ve ended up like Bill, or like Linus, or like the guy drowned in his own net, and I think how I might’ve never known anything about him if his body hadn’t crashed back through the roof of my life, and now, the awful power of my mind left alone, I see him in one of those photos, on some rocks. Ha! Uncanny! The shit I get into when I drink! But now the dream of falling forward. The drunken momentum of memories. I’m nodding off in class, I’m nodding off on the slime line, I’m not so much moving as being carried from the barstool, through the swinging half-door, behind the bar, past the beer taps, past the cash register. In the photo, he’s older and fatter and bearded. Dad/not dad. He’s wearing raingear and the picture is water stained and grainy. I turn to the drunk and say, “Hey did you know this guy?”

“You shouldn’t be back there.”

“Him.” I point.

“Really, you shouldn’t.”

Now I’m shoving it in his face. “This guy. This fucking guy right here.”

His eyes are crossed and he’s trying to make sense of it. “Yep,” he says. “Joe. I heard he fell off something and died.”

“Duane,” I say. “His name was Duane.”

“No,” he says. “Pretty sure that’s Joe.” But before I can ask anything else, the door from the kitchen crashes open and I’m getting laid upside the head with some sort of club and the bartender is screaming at me and my father’s picture hits the floor and breaks. I keep trying to explain but she keeps swinging and screaming THIEF and there are packs of cigarettes everywhere and bottles breaking and why are all the women in this state so fucking strong? I got ahold of the club and now she’s kicking my shins and there’s a hot liquid on my cheek and then the sound like getting slapped in both ears.

The old drunk’s holding the gun, smoke in the air. A chip of plywood falls from the hole he put in the ceiling. He looks at the gun with a face full of surprise. An innocent, stupid face. The face of the dead whale. The bartender screams, “What in the fuck did you do that for?” and as they face off to argue about it, I bolt out the kitchen door into the gravel lot.

__________________________________

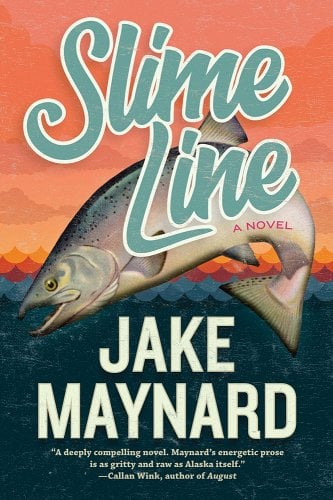

From Slime Line by Jake Maynard. Used with permission of the publisher, WVU Press. Copyright © 2024 by Jake MaynardCopyright © 2024