Searching for Salvation in Charlotte Brontë’s Villette

Two Pauls, Two Loves, Two Separations

Paul was flying. As I lay supine in the intensive care unit, an IV threaded into the skin of my forearm, his face flickered in the damp vagueness between eye and lid. His body, I knew, hovered that very minute over clouds and terrain as a plane carried him back to Colorado and away from me. He or I might as well have been apparitions, so total was our estrangement. But with eyes clamped shut his ghost seemed close company, and I could entertain the fantasy that we haunted each other.

Paul and I met the fall of 2010, one month after I had married someone else. That December, after a tremulous and fleeting affair, I confessed the transgression to my husband and performed penance via one bottle of Tylenol. Now I was confined to suicide watch, my only visitors an understandably infuriated husband and my best friend. From that bed I had submitted to my husband’s directions and composed an email to Paul, bleached of all sentiment, terminating our relationship and any further correspondence. The blame for this misery was mine entirely. Through my own puppyish judgment I had rendered romance and marriage alien circumstances.

* * * *

That was the winter I reread Charlotte Brontë’s Villette, one of my favorite novels, and the one that makes me most lonely. I have always revisited it lovingly, but with trepidation. A conventional devotee, I introduced myself to the Brontë sisterhood through Jane Eyre—and to this day I am more inclined to return it than I am to wade into to any other novel by Charlotte, Emily, or Anne. For I am, admittedly, a hungry-hearted creature; I crave protagonists who seem to welcome my company, whose narration pulsates with our mutual desire: see me, hear me, witness me. Jane demands that we read her according to her own terms—she withholds and confronts, retreats from the novel’s conclusion—but throughout the expanse of her narrative she brushes against our fingers. She reaches for us, and we open our arms.

Brontë wrote Jane Eyre and Villette in a literary and cultural milieu bridled by men, one that instructed women in the choreography of docility and accommodation. As both character and narrator, Jane rejects these conventions; she is defiant, sometimes clamorously so. Villette’s protagonist, the cagey, deep-hearted Lucy Snowe, also refuses the mantle of solicitous femininity, coolly acknowledging our expectations of a female narrator and elegantly disregarding them. “It will be conjectured that I was of course glad to return to the bosom of my kindred,” Lucy remarks in an early chapter, in reference to her return from a long visit. But though she anticipates her readers, she is disinclined to correct them, choosing instead a cloak of cynical obscurity. “Well! the amiable conjecture does no harm, and may therefore be safely uncontradicted,” she says, sarcasm lilting and pointed, “I will permit the reader to picture me… as a bark slumbering through halcyon weather… A great many women and girls are supposed to pass their lives something in that fashion; why not I with the rest?” Why not, indeed? Because as Lucy Snowe knows all too well, that narrative of domestic tranquility—flush with silks and billets doux, steadied by benevolent patriarchy—is for most 19th-century women a rattling husk. We may assume this much is the case for Lucy Snowe—or perhaps it’s more fitting to say that we have no recourse but to assume.

And yet, Lucy’s heart is not entirely alien to us. In time she confides to her readers the romance she nurtures with the curmudgeonly M. Paul Emmanuel. We know her passion, rare in its distribution but abundantly bestowed upon those whom she loves best.

Like Paul. Above all others, Paul.

* * * *

I’ve always wanted too much from Lucy Snowe. When I reread Villette after falling in love with a Paul of my own, I snatched at the frail thread barely traceable between our plotlines: two Pauls, two loves, two separations. Superstition takes hold when our lives crack open. I needed more than a novel; I yearned for a talisman. I sifted through Villette’s pages, convinced that my own fortune could be divined in the interstices of Lucy’s story. Agnostic since youth, I had no higher god to appeal to than narrative. If my deliverance were conceivable, then it would be through Charlotte Brontë.

“My heart will break!” Lucy exclaims. So long an unobtrusive observer, willing to love in silence, she is at last stirred to action when threatened with her beloved Paul’s departure. But I had already acted, poorly. And my heart was already broken.

* * * *

Then there is the matter of the ending. Lucy and M. Paul confirm their love, and although he does embark on a voyage, it is with the promise of return in three years’ time. “Lucy, take my love,” Paul beseeches, “One day share my life. Be my dearest, first on earth.” Finally, Lucy Snowe is adored as we have longed for her to be, as she deserves to be. We exhale in relief, because she will be happy—and for three years she is. I had not forgotten, when I reread the novel, that Lucy’s most blissful years pass in absence of her lover. Nor had I forgotten what she only implies: that she and M. Paul are never reunited. I simply was determined to discern an ending different from the one I had always imagined.

Lucy heralds Paul’s return as a second coming. Her words are drenched in prophecy; they bear all the gravity of liturgical foretelling: “The sun passes the equinox; the days shorten, the leaves grow sere; but—he is coming.” Briefly, wonderfully, Paul’s return to Villette seems inevitable. So many 19th-century novels conclude in marriage, why not this one too? But Brontë knew this well-traveled plot trajectory, and both she and Lucy rebuke its tidiness. They also deny us the finality of death—terrible, yes, but known.

So many 19th-century novels conclude in marriage, why not this one too? But Brontë knew this well-traveled plot trajectory, and both she and Lucy rebuke its tidiness.

Instead, we learn of a storm at sea, one that will certainly wreak havoc on the ship carrying M. Paul. All of a sudden, the promise of destruction overtakes the certainty of a lover’s reunion. “He is coming,” Lucy tells us—and so it is written. But it is never written that he came. A tempest rages, and we bear witness to Lucy’s powerlessness to protect: “It will rise—it will swell—it shrieks out long: wander as I may through the house this night, I cannot lull the blast.” Earlier in the novel, Lucy retreats into the obscurity of a twin metaphor when referencing a childhood trauma: “the ship was lost, the crew perished.” The events themselves are never unearthed; we only know that from early adulthood, Lucy is alone in the world and impoverished. Has she, at the novel’s end, rendered this allegory explicit? Can M. Paul be safeguarded back to Lucy nonetheless?

Lucy refused to tell me. In college, when I first read Villette, I dwelled upon the novel’s last paragraphs in mild agitation and melancholy. Now, issued from the hospital and into the custody of a betrayed husband, I wrestled with them, hell-bent on wringing cheer from their obliqueness. Yet the only clues pointed to devastation—my only remaining alternative was to adopt Lucy’s boilerplate ending as truth:

Trouble no quiet, kind heart; leave sunny imaginations hope. Let it be theirs to conceive the delight of joy born again fresh out of great terror, the rapture of rescue from peril, the wondrous reprieve from dread, the fruition of return. Let them picture union and a happy succeeding life.

Let them picture it, because it is not Lucy’s duty to tell us, regardless of the outcome. Throughout Villette she has rigorously guarded her privacy, and now, at this charged moment, she will entertain us no further. If she’s grieving, if she’s rejoicing—it is not for us to know.

* * * *

I longed for Charlotte Brontë to narrate my life, to choose in my stead. She would not, and neither would Lucy; the comfort of projection was not mine to enjoy. Lucy settles on the course of her story: it drifts into the shadows, out of reach. I was free—and, so it seemed, condemned—to determine my own way. That gossamer thread I had fantasized as a lifeline between Villette and myself evaporated into mist. I have not willed its return. My love for Brontë’s novel is no longer predicated upon answers sought and furnished, nor do I ask Lucy to shed her ambivalence. For who among us could do the same, even in the most felicitous circumstances? Revelation, truth—these are flickers of electricity that startle us out of our lingering uncertainty. They are blessed moments, but they are merely visited upon us. We must also find the pleasure in ambiguity—that is, after all, where we live.

Yet what is already past I can see with clear eyes. And so, I will tell you (a Lucy Snowe I most certainly am not). Paul and I passed half a year as strangers, and I tried to be a wife to another man. I failed cruelly in that endeavor. One day, after long, aching months of studying and teaching in the same graduate department, Paul stopped by my office so that we could suss out a more tolerable way of coexisting. I loved him for his courage and his calm—and because in loving him I was more legible to myself, more me than I had ever been before. He did not ask me to choose a new life with him, but reader, I did.

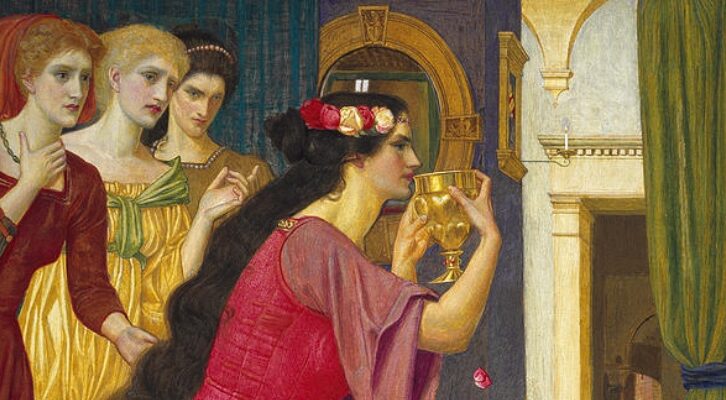

Feature image: detail from Ivan Konstantinovich’s Ship in Stormy Sea, 1858.