Reading in the Wake of

My Mother's Suicide

"I Wanted to See How Other People Had Lived Through This Kind of Loss"

After our mother took her own life in the midst of a psychotic break in 2009, my sister attended peer-led counseling sessions for suicide loss survivors in Toronto. It was a wonderful, helpful, program, but I doubt I would have participated, had I been able to find a similar one in Southern California. I had given birth one week before our mother killed herself and wasn’t getting out of the house much. In my postpartum state of mourning, I had shut myself in, shut myself down. It was hard to be out in the world—I felt as if I had no skin, my body a mess of exposed nerve; I was a mess, in general, fearful of everything, sure if I brought the baby anywhere, he’d catch some deadly disease. I turned, in my own introverted, to a different method of peer-led counseling; I turned, as I have throughout my life, to books.

I wasn’t interested in advice or self-help, wasn’t interested in research or statistics, at least not at that point. At that point, all I wanted was story. I wanted to see how other people had lived through this kind of loss, how they had made sense of the shock, the blindsiding blow of it. I wanted to see how other people had struggled, how other people had healed, if healing was even possible. I wanted to know I wasn’t the only one to thrash around in this stew of guilt and anger and devastation and, at times, relief (which of course brought its own stripe of guilt).

The memoirs I found from people who had lost loved ones to suicide saved me, as did my sister, the one person in the world who knew this particular loss on the same cellular level. We passed books between us like oxygen masks. Joan Wickersham writes about gravitating to other survivors of suicide loss: “We find each other,” she notes. “We’re referred by friends. Or we happen to sit next to each other on an airplane. We end up standing together in a hallway, during a party. We stop noticing who is coming and going around us. We talk. It’s urgent. We have nothing new to tell each other. Even when the stories are different, they’re the same.” I felt the same way about the narratives I found about suicide loss. They all felt urgent; they all felt invigoratingly different and comfortingly the same; they all made the rest of the world fall away as soon as I opened them; they all felt deeply, deeply necessary. I inhaled them greedily, felt them enter my bloodstream, fortify my heart.

And these books offered more than solace, more than a sense of connection. That would have been enough, but I knew I was mining them for inspiration, too. I wanted to show myself that other people had been able to write about this kind of loss, to remind myself that if they could be this brave, if they could give shape to their own chaos through words, so could I.

Joan Wickersham, The Suicide Index

A formally inventive memoir about the suicide of Wickersham’s father, The Suicide Index captures the way this kind of grief resists traditional narrative in short, alphabetic entries. This book empowered me to play with structure in my own memoir, which blends present-tense narration around the time of my mom’s suicide with epistolary writing, film transcripts, and research. Hers was the first book I read after my mother’s death, and it opened my mind and heart to possibilities for connection, for expression.

Nick Flynn, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City and The Reenactments

Nick Flynn’s memoirs aren’t centered around his mother’s suicide but are deeply informed by it. He faces her death head-on in his earlier book, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City; later in The Reenactments, he explores the very particular and complicated pain of seeing her suicide recreated in the film of the first book. “Am I hoping to take something that was (my mother, her death) and present it as I hoped it would be?” he writes. “Or am I taking something that was and making something out of it that will last forever? Am I reenacting a—her—death, or am I hoping to bring her back?” His work is a powerful braiding of empathy and imagination with rigorous investigation of self and world.

Linda Gray Sexton, Searching for Mercy Street and Half In Love

Linda Gray Sexton tackles the legacy of her larger-than-life mother in two memoirs. In Searching for Mercy Street: My Journey Back to My Mother, Anne Sexton, Sexton delves deeply into her childhood—her adoration of her mother, as well as the harrowing emotional and sexual abuse her mother inflicted upon her in the midst of drinking binges and psychosis. In Half in Love: Surviving the Legacy of Suicide, Sexton focuses upon how she’s stepped into her mother’s shoes as an adult, not only by becoming a writer, but also through her own struggles with depression, her own attempts at suicide.

Karen Green, Bough Down

Karen Green, David Foster Wallace’s widow, weaves art and text together in this luminous, aching portrait of grief. In passages like “(And when he gave way, was there room for feelings or the words for feelings?) While I brush my teeth, I can see him in my periphery at the other sink. The outline of him lulls and stings. (And when he gave way, was it the end or the beginning of suffering?)” she illuminates that sometimes, we don’t have the answers to our stories, but we can make art out of questions.

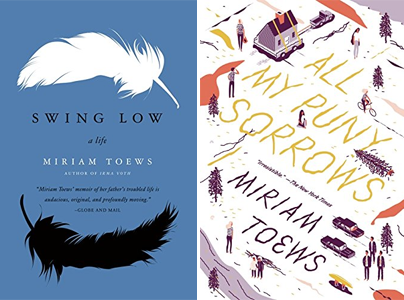

Miriam Toews, Swing Low and All My Puny Sorrows

Toews’ memoir, Swing Low, explores her father’s suicide; her novel, All My Puny Sorrows, was written after her sister died by suicide as well and offers a fictionalized account of this loss. My sister sent me the novel from Canada before it was published in the US. We were both grateful for the way in which Toews captured the strange sweetness of shared grief along with the gut punch of it, how she wove humor into her wrenching tale. There were definitely some funny moments around the time of my mom’s death, and it was relieving to see that humor doesn’t necessarily disrespect pain—in fact, it often accompanies it, and to leave it out would be dishonest.

Peter Handke, A Sorrow Beyond Dreams

Peter Handke wrote this slim but potent memoir about his mother’s suicide in the span of two months shortly after her death. He writes “I had better get to work before the need to write about her, which I felt so strongly at her funeral, dies away and I fall back into the dull speechlessness with which I reacted to the news of her suicide.” The whole book carries a sense of urgency, as if he’s writing against the clock, as if he’s rushing to get the words out before they disappear—words about his mother’s life in Austria before, during, and after WWII, words that plumb his experience of grief. Toward the end of the book, one can sense the words starting to peter out; many of the later paragraphs consist of only a single sentence, as if Handke is starting to lapse into the speechlessness he had feared. This feels more like an earned speechlessness than a tragic one, though, as if he could finally rest after finding the catharsis he needed.

__________________________________

Gayle Brandeis’s memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis is available now from Beacon Press.

Gayle Brandeis

Gayle Brandeis is the author of Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write and the novels The Book of Dead Birds, which won the Bellwether Prize for Fiction of Social Engagement, Self Storage, Delta Girls, and My Life with the Lincolns, which received a Silver Nautilus Book Award and was chosen as a Read on Wisconsin pick, as well as a collection of poetry, The Selfless Bliss of the Body. Her essays, poems and short fiction have been widely published and have received numerous honors. She teaches in the low residency MFA programs at Antioch University, Los Angeles and Sierra Nevada College, where she was named Distinguished Visiting Professor/Writer in Residence.