Please Stop Talking About the "Rise" of African Science Fiction

Tade Thompson Breaks It Down: African SFF Has Always Been Here

Whenever I see an article that starts with “The Rise of. . .” I think of dough. When it’s applied to African science fiction, I picture an endlessly rising (and falling) dough that will never become bread. Each “rise” is celebrated but ephemeral, existing only until the next event that is itself seen as a “rise” without reference to what has gone before, leaving the field oddly ahistorical to the uninitiated.

In 2009 there was a confluence of events in the science fiction and fantasy (SFF) landscape. Racial and cultural tensions within the genre came to a head in what is internally referred to as Racefail ’09—a series of blog posts, responses, comments, and counter-comments about the representation of People of Color in SFF. A big budget movie called District 9, though flawed, earned four Oscar nominations and brought African Science Fiction into the limelight. Pumzi, a short SFF film, was made and released by Wanuri Kahiu, from Kenya.

It’s possible you’ve never heard of any of these events, but they all conspired to bring us the Black Panther movie (and you’ve certainly heard of that unless you’ve been hiding under a vibranium-laced rock). But it’s not the first African narrative to feature a hidden, technologically advanced city (that honor probably belongs to Golden Gods [1934] by George Schuyler).

What links District 9 and Black Panther, two films almost ten years apart, is the response of the Western consumer. Both triggered a demand for articles about the “Rise of Afrofuturism” or “African SFF” or similarly titled pieces. But a even casual perusal of the genre shows there’s sufficient creative work to make such articles unnecessary, or, worst case, perpetuators of a gentle literary oppression that keeps African science fiction infantile.

I will say that there is a difference between African SFF and African-American SFF and Afrofuturism, but the two are so intertwined that I predict in a few years it will no longer be a useful distinction, with Afrofuturism becoming the umbrella term. I’ll stick to African SFF, which itself is problematic because who is an African? I say this so that the reader may know there’s a great deal of intersectionality here, cutting across ethnicity, nationality, religion and so on.

What I would like to do here is give a few examples that show African SFF across the ages, to hopefully demonstrate the amnesia that fogs things up until the next big budget event like, say, Black Panther II: Vibranium Boogaloo.

Many of the earliest works have a tendency to skew literary, and it is doubtful if the authors would self-identify as writing SFF. Though African-American science fiction dates back to the 19th century [The Huts of America, 1859], the first African SFF books are arguably Gandoki (1934) and Nnanga Kon (1932)—with honorable mention to Thomas Mfolo’s Chaka (1925).

Nnanga Kon/ Le Phantom Blanc by Jean-Louis Njemba Medu means “white ghosts” or “phantom albino” in Bulu, and won the International African Institute Competition for 1932. It casts white colonialists as technologically advanced supernatural beings and is a powerful first contact narrative which spawned folktales in Cameroun.

Gandoki (1934) by Muhammadu Bello Kagara also involves encounters with Colonialists, only this time it is Nigeria, there is resistance as well as travel to other realms and phantasmagorical experiences with djinn. A similar, but more episodic book is Forest of a Thousand Daemons (1939) by D.O Fagunwa, which describes the hunter Akara-Ogun’s adventures in an enchanted forest.

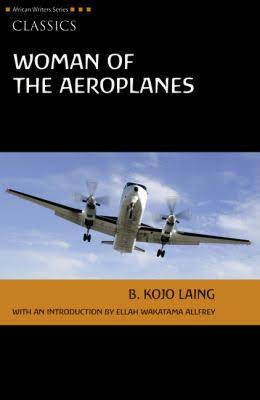

Woman of the Aeroplanes (1988), a book of lush language and great imagination by Kojo Laing is a lyrical exploration of an African village quantum-entangled with a town in Scotland.

The Famished Road (1991) by Ben Okri relates the experiences of an abiku (a Yoruba spirit child), interweaving the supernatural and material world, earning the author the 1991 Man Booker prize.

African SFF from the new millennium began to shift into traditional territory, becoming concerned with futurism, space travel and the environment. Savannah 2116 AD (2004) by Jenny Robson is a futuristic novel with an environmentalist bent.

The most significant writer in African SFF is Nnedi Okorafor. After a distinguished career in children’s fiction, her 2010 novel Who Fears Death became a milestone. It won the 2011 World Fantasy Award and the 2010 Carl Brandon Kindred Award. The book was also nominated for a Nebula Award and a Locus Award. She has won the Hugo award and been nominated for every major science fiction accolade.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention Zoo City by Lauren Beukes, Muna Hacha Maive Nei? by Masimba Musodza, Azanian Bridges by Nick Wood, A Stranger in Olondria by Sofia Samatar, Nigerians in Space by Deji Olutokun, Taty Went West by Nikhil Singh, Blackass by Igoni Barrett and the collection A Killing in the Sun by Dilman Dila.

Africans have been writing science fiction since at least the 1920s, and have produced bodies of work in literature and sequential art to the present day, work which has won critical acclaim and literary awards. Because of all the above, it would be difficult to justify the idea of an “emerging” African interest in science fiction in 2018. The perpetual existence of “Rise of” articles resembles what Toni Morrison was talking about when she said, “It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining over and over again, your reason for being.”

Back to my admittedly weak metaphor, if you are a person who bakes, you’ll know that letting dough rise for too long spoils the bread.

African science fiction is not rising. It is here.

Tade Thompson

Tade Thompson lives and works in the south of England. He is the author of the Rosewater trilogy (winner of the Nommo Award and John W. Campbell finalist) , The Murders of Molly Southbourne (nominated for the Shirley Jackson Award, the British Science Fiction Award, and the Nommo Award), and Making Wolf (winner of the Golden Tentacle Award). His interests include jazz, visual arts and MMA.