On the Use of Sensitivity Readers in Publishing

A Writer, Reader, and Publisher Weigh In

In the past few years, authors concerned about the accuracy of their cultural representations have started using a new tool. Sensitivity reading, or beta reading, involves manuscript review where the author is writing about a marginalized group to which they doesn’t belong. A sensitivity reader might have a particular medical condition, sexual orientation, ethnic background, or any experience or identity that may be poorly understood by the majority culture.

Some might consider the use of sensitivity readers an eye-rolling exercise in identity liberalism that has become bruised a bit by recent political events. To others, sensitivity reading is a welcome means, though by no means a sufficient one, of working towards a more inclusive and less cliché-ridden publishing industry.

Here, three people working in YA literature—an author, a reader, and a publisher—discuss their experiences with sensitivity reading and offer some suggestions to optimize its benefits.

A Writer’s Perspective

Becky Albertalli. [Decisive Moment Events.]Becky Albertalli’s experience with sensitivity readers provides a useful snapshot of this trend. When she was writing Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda, published in 2013, she hadn’t heard the term “sensitivity reader.” But the book, which centers on a closeted teenager, passed through the hands of many gay men as part of the process of consultation. This was basically a form of sensitivity reading, although not formalized.

Becky Albertalli. [Decisive Moment Events.]Becky Albertalli’s experience with sensitivity readers provides a useful snapshot of this trend. When she was writing Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda, published in 2013, she hadn’t heard the term “sensitivity reader.” But the book, which centers on a closeted teenager, passed through the hands of many gay men as part of the process of consultation. This was basically a form of sensitivity reading, although not formalized.

When it came time to write her next book, The Upside of Unrequited, sensitivity reading had become more familiar. We Need Diverse Books was launched in 2014, and major lists of available sensitivity readers were created in 2016. For this book, Albertalli wanted to be much more deliberate about the process.

The protagonist of The Upside of Unrequited, which will be published in April 2017, is a fat, anxious, cis, straight, Jewish teenage girl; this adjective soup is autobiographical for Albertalli. Other significant characters include women in relationships with other women: one who identifies as pansexual, for instance, and two moms: one who’s bisexual, while the other is a lesbian. Albertalli had people who shared these and other identities read the manuscript, adding up to a total of 12 sensitivity readers. “I can’t even explain how grateful I am, because there are things I wouldn’t have thought of that are an easy catch for people who have lived through that experience,” she says.

One example came in the very first scene of the book—which Albertalli wryly notes was a high-stakes situation. Here the narrator mentioned outright that she was straight. A bisexual sensitivity reader critiqued the overtness of this, saying, “That comes off as super ‘no homo’ to me.” Albertalli agreed. It was obvious by page two that this character was straight, and she realized that in aiming for political correctness, she had struck a false note. She reshaped the scene.

Albertalli’s respect for her sensitivity readers, and for the process itself, is clear. She estimates that she made changes with regard to 100% of the serious suggestions made by these readers, and 90% of the more minor ones. If a writer is inclined to reject a recommendation made by a person who, unlike the author, has lived the experience of the character she’s writing, Albertalli feels that it’s worthwhile for the writer to get a second opinion.

All this isn’t to say that anyone identifying with a certain community can ever speak for all members of that community. In Albertalli’s case, another Jewish reader went through The Upside of Unrequited and mentioned something that didn’t square with her own experience—unsurprising, as there’s no one way to be Jewish (or bisexual, etc.). And, in particular, intersections of multiple identities make for combinations that can’t be easily reduced to a single affiliation.

A Reader’s Perspective

Sangu Mandanna.

Sangu Mandanna.

Sangu Mandanna is an author and editor who has been doing formal sensitivity reads for over six months. She’s listed on the best-known database of sensitivity readers, compiled by Writing in the Margins, a resource created by YA author Justina Ireland.

Mandanna’s experience inhabiting these multiple roles shows that sensitivity reading makes for a unique set of demands on a reader/editor. “You’re not looking for plot holes or world-building inconsistencies, for example; you’re looking for places in the text where [characterization] or a narrative arc or even just a turn of phrase could be a problematic or downright harmful representation.”

These can be seemingly minor issues, but the very fact that they’re often overlooked points to the ease with which a majority culture can reproduce stereotypes. Mandanna gives as an example the frequent exoticizing of brown characters. “Take phrases like ‘glowing brown skin’ or ‘eyes like jewels’, which are phrases I see very often. These phrases are meant to be positive, but the author would never use them to describe their white characters.”

Like Albertalli, Mandanna talks about preserving an open dialogue between the author and sensitivity reader, and the importance of respecting limits. For instance, Mandanna says she “once flagged a point about India up in a manuscript because it wasn’t true to my experience of the country. It was true to the author’s experience, however, and we both agreed she should keep that point intact.” Exchanges like these may prove most valuable when authors don’t view a sensitivity read as a one-off service, but a departure point for conversation.

A difficult conversation the literary community needs to have is about whether there’s a danger that sensitivity reading for majority-culture authors may displace attention to minority-culture authors themselves. This isn’t either/or, of course. “I think there’s space for authors to write about groups they don’t belong to and I think they absolutely should, if only to reflect the natural diversity of the world authentically,” Mandanna says. But she feels that the priority should go to own voices work (or writing about marginalized groups by members of those groups themselves), which is already in such short supply.

Mandanna also cautions against over-reliance on a sensitivity reader. There have been unfortunate cases of authors being criticized for portrayals of marginalized cultures and then attempting to deflect blame onto their sensitivity readers. Ultimately, the buck needs to stop with the author. “Too many authors use a sensitivity reader and then assume they can’t possibly go wrong, but sensitivity readers aren’t infallible and they’re not supposed to be. They’re a resource, not a shield.”

A Publisher’s Perspective

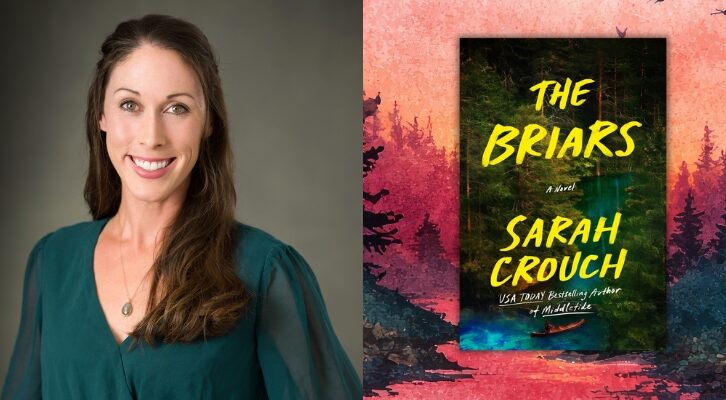

Two of Tu Books’ latest publications.

Two of Tu Books’ latest publications.

Stacy Whitman is the publisher of Tu Books, the middle-grade/YA imprint of Lee & Low Books. Lee & Low focuses on characters of color, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that it’s standard practice at the company to bring in sensitivity readers when an author is writing cross-culturally. The term used at Lee & Low is “cultural expert.”

This doesn’t just apply to manuscripts in the editing stage. Whitman advises authors to plan enough time with sensitivity readers early enough in the writing process so that major developmental changes can be made if needed. Otherwise, a sensitivity read could become a bandage, applied retroactively, when preventive medicine would have been more appropriate. On the publishing side, Whitman explains, “We send books to experts at various stages, depending on our needs, as well—if we are acquiring a book we don’t have in-house expertise in (such as a culture we’re not as familiar with), we might even run it past an expert before acquisition.”

This rests on cultivating relationships with trusted readers. At Lee & Low, “We have relationships with a wide variety of people from many different cultures and backgrounds. When we have a book outside the author’s experience culturally (or outside their experience of identity, as with an LGBT character), we look at who we know who might be an expert in the subject, and then network from there to find someone who is a good fit,” Whitman explains.

The exact form a sensitivity read might take varies. In general, “We ask the expert to evaluate the manuscript on a particular subject, not give overall feedback. But the scope of their feedback varies depending on the amount of cultural content and how that content interacts with the rest of the story.” If the subject matter is particularly controversial, Lee & Low might call in several sensitivity readers to examine the same issue.

This isn’t just a box-ticking exercise, as Whitman sees sensitivity reading as genuinely improving literary quality. “In general, cultural and subject-matter experts help make a better book! And that’s the goal—always making the best book possible.”

Ways Forward for Sensitivity Reading

This discussion raises a few suggestions for others in publishing looking to become involved in sensitivity reading. For one, it’s important for authors to have some humility about the mistakes they’re likely to make. Albertalli acknowledges in regard to her upcoming book, “I went into it thinking that I was going to screw up, and I was ready to make those changes.” Defensiveness about proposed suggestions benefits no one. “Don’t approach from the perspective of ‘I hope there are going to be no changes, I hope I didn’t screw up too badly’,” cautions Albertalli of the hazard of rubber-stamping. “When a sensitivity reader gives you an idea that you can use to make it better, that’s a huge gift and something to get excited about.”

It’s also important for publishers to support the process in whatever way is most appropriate: financially, by covering the costs of sensitivity readers; logistically, by drawing on their networks; or editorially, by working with authors to think through recommended edits.

And for publishers and authors both, Albertalli points out the need to recognize power dynamics. There’s the obvious matter of fairly compensating a sensitivity reader (Writing in the Margins recommends a starting rate of $250, although some authors may prefer to swap services as part of a writing and reading community). More generally, though, responsibility for the process should ultimately lie with the author—it isn’t reasonable for a reader to be liable for problems with a text that they didn’t write, as Mandanna’s comments attest. One way for an author to absorb this responsibility is to obtain permission from sensitivity readers before acknowledging them by name.

When it comes to ensuring that everyone’s time is used efficiently, Whitman emphasizes the importance of author preparation. This would involve reading up on the basics of not just the subject matter, but also, for instance, how to avoid racist tropes. She counsels, “Don’t pass up opportunities to learn from the huge amount of diversity work happening online now. Follow authors and educators of color on Twitter, read their blogs, read American Indians in Children’s Literature, Rich in Color, Diversity in YA.”

Sensitivity reading isn’t the be-all end-all of promoting diverse and responsible books. Rather, it’s one step in a constant process of developing cultural awareness, which can only make writing more accurate, yes, but also more interesting and illuminating.

The increasing prominence of sensitivity reading points to some reasons for optimism. Mandanna says that the authors she works with tend to have good intentions, and that this is especially true of writers who are keen to work with sensitivity readers. In her view, these writers may already be “more aware of how easy it is to make a harmful mistake and are already ahead of the curve, in that they want to avoid making those mistakes, if possible.”

Still, it would be useful to expand the practice of sensitivity reading to those authors (and genres) who tend to assume that their experiences and research are sufficient when portraying marginalized groups. It may be that YA lit, for reasons including the strong presence of women behind the scenes, has been a more welcoming home to diversity-enhancing measures. One challenge will be to apply lessons learned in YA to traditionally male-skewing genres—as well as other types of culture, such as games.

Christine Ro

Christine Ro has written about books for Brooklyn Magazine, VICE, Ploughshares, The Big Issue, and Wink Books. She has a bad habit of forgetting all but the last three books she read.