On Envy, the Internet, and Diana Ross

Jami Attenberg and Maria Semple in Conversation

I first met Maria Semple on the floor of BEA in between the booths of our publishers, an unromantic setting, the Javits Center, but this is how we meet each other sometimes. She talked a mile a minute, this charming rat-a-tat-tat, and she was confident and assertive and, unlike most writers—god bless our neurotic hearts—she seemed like a real professional in just existing in her skin. I grabbed a galley of her book, the brilliant and entertaining Where’d You Go Bernadette, which went on to spend a year on The New York Times bestseller list, and has been optioned for film with Cate Blanchett to star. I have since become friends with Maria, and I can tell you three things about her: she has read everything, she is an autodidact, and I have never heard her utter the words, “I don’t have an opinion on that.” Lauren Groff calls her newest book, Today Will Be Different, “…searingly honest and hilarious and dark and neurotic.” I call it witty and cranky and smartly structured and deeply satisfying. Do you like good books? Boy, do I have one for you.

Maria and I emailed for a few days about being a troublemaker, professional jealousy, Diana Ross, and other important matters.

–Jami Attenberg

Jami Attenberg: Hi Maria! Let’s start with something very simple. Are you the kind of writer who likes the actual act of writing, being in the moment, or do you prefer having written, just seeing a big pile of words in the rearview mirror?

Maria Semple: Good morning to you, Jami! It’s the Gore Vidal quote about writing. “It’s hard to start and impossible to stop.” God, I just checked the internet and can’t find that quote anywhere. Maybe Gore Vidal never said that and I’ve been going around all these years saying he has.

JA: Maybe you said it, Maria.

MS: I’d never say something so succinct . . . which you’re about to find out the hard way! Yes, I love the act of writing. It fills me with fiendish delight, devising ways to cause trouble.

JA: Do you have a vision of what kind of trouble you want to cause?

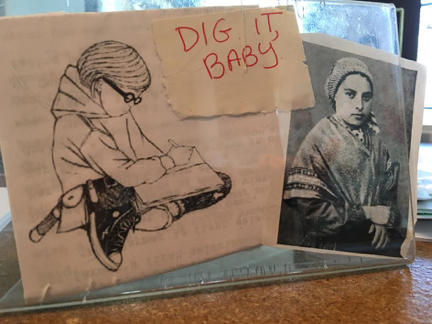

MS: All kinds: forcing my characters into terrible jams, writing myself into story corners, wrestling impossibly tangled ideas into words. On a personal level, I get a sick thrill from finding an aspect of myself that is too ugly to expose, then doing it anyway, or coming up with a highly specific rant that nobody else could possibly relate to and committing to it. My basic premise being that if I keep it exciting for myself, the rest will follow. Here’s a reminder, which I keep framed on my desk.

JA: I see Harriet the Spy, consummate troublemaker there. But who is the other woman?

MS: Harriet watched over the writing of Today Will Be Different. That’s Saint Bernadette of Lourdes who kept watch over Where’d You Go, Bernadette. (A real trouble-making nut job, can’t you see the no-good in her eyes?)

JA: I always think about how I write the first draft for myself, the second draft for my editor, and my third draft for my presumed audience. And I love that revision where I am in a kind of conversation with the bigger world. Do you calculate that into it at all eventually, that there’s an audience out there?

MS: I’m constantly thinking about the reader. John Gardner, in either The Art of Fiction or On Becoming a Novelist, said that fiction writing must be an act of generosity. I see myself as a benevolent hostess. I want to throw the perfect dinner party for my readers. Or, I should say, I’m always asking myself, “What’s the most fucked-up thing that can happen now?” Because when I’m reading a book, I want to be pulled in, thrown off, messed-with, ambushed. (I’m sure you’re thinking, note to self: never go to a dinner party at Maria’s!)

JA: I am thinking to myself: Can I please go to a dinner party at Maria’s house?

So voice is a huge part of this, being a hostess. Do you have any thoughts on your discovering your voice in your writing? Is there anything to getting older and knowing your voice? In some ways I have had to give myself permission to fully explore/explode my voice, and I don’t think I could have totally done that when I was younger, or maybe I was not able to have the honesty needed.

MS: Voice has been a long, complicated journey for me, and yes, it’s developed with age. Anyone who knows me knows I talk fast, talk a lot (with varying degrees of coherence), over-share, go off on loop-de-loops, cry on a dime and frequently appall. You’d have to say that’s my voice. I wrote my first novel, This One Is Mine, in spare-ish third person. Back then, I thought that’s what novelists did, write at a remove. But the more novelists I met, the more I realized their voices directly corresponded to their personalities. Weird, tight-assed people wrote weird, tight-assed novels. Smart, kind-hearted people wrote smart, kind-hearted novels. With Where’d You Go, Bernadette I started out in first person, in Bernadette’s/my voice. But she became really toxic really fast. If even I felt like taking her out back and shooting her by page 20, how would the reader feel? So I found it necessary to fold in other voices . . . which is how it became an epistolary novel.

With Today Will Be Different, I decided to let it rip. In the beginning, Eleanor comes on fire-hose strong. I gave it a name: “The Trick.” One of my delights was playing with the readers’ relationship to “The Trick.”

JA: In Today Will Be Different, Eleanor has a fascination with poetry, which made me wonder if you dabbled in that as well.

MS: I’m a philistine when it comes to poetry. Like Eleanor, I met weekly with “my poet” Ed Skoog, who’d assign me a poem to memorize, I’d recite it, and we’d see where the conversation took us. It was a divine chapter in my life, over now only because Ed moved to Portland. I’m immensely intimidated by poetry and feel like I need it explained to me. Memorizing poems is something I highly recommend to all writers. I can usually nail down 90 percent of a poem in an hour or two. But that final 10 percent is where the magic happens. Your brain wants to fill in words in a habitual way. Forcing it into a different direction, you can practically feel your brain expanding and rewiring itself. Who needs LSD when you can memorize “Skunk Hour”?

JA: I feel like men named Ed are always moving to Portland! I have this theory that poets are the purest of all the writers because they absolutely have to do it for love because there’s basically no way to make a living at it.

MS: When I first met my Portland Ed, I gushed with sympathy about his decision to become a poet, how it must be a wretched and destitute existence. He had a jolly laugh and assured me that poets are the ones getting away with the whole thing!

JA: Do you ever miss Hollywood? I’m simultaneously terrified and dismissive of it. Like I think I’m probably more terrified because I feel like there’s this shroud of mystery around it that I can’t understand and never will, there’s a specific language, and also an assessment of people, this Robocop-like assessment if you’re culturally/commercially relevant enough. But I get to be dismissive of it because I have this safe harbor in writing books.

MS: With Hollywood you’re certainly only as good as your last credit… to a cruel/idiotic/hilarious degree, depending on your state of mind the day you’re getting the shaft. As humiliating as my resting state was while I was in LA, I was always grateful to be a writer. Writers, unlike actors or directors, control their own destiny. I’m a firm believer that good material gets rewarded. Not necessarily in the form of a frenzied auction and a seven-figure deal. But someone will remember you when it’s hiring time for another project, or be favorably inclined to read the next one. Who knows how the tendrils of fate work? Faith is required.

For better or worse, when it comes to Hollywood: those are my people. I miss the neurosis, the intensity, the shorthand. In my new book I have a line where Eleanor says of New Yorkers . . . excuse me while I refer to the Torah . . . “Living too long in New York does that to a girl, gives her the false sense that the world is full of interesting people. Or at least people who are crazy in an interesting way.” That’s how I feel about Hollywood. My father Lorenzo was a fancy-pants screenwriter; there were always actors, writers and directors hanging around. Archie Bunker drove carpool. For share day, Bob Newhart Jr. had his dad come in and do standup. I’m neither intimidated nor impressed by show business types, just comfortable. I feel so fortunate that as a novelist Hollywood doesn’t have a mythical power in my personal cosmology.

JA: Novelists have mythical powers in my cosmology. One of our shared joys is old Paris Review interviews. Can you talk about any you love in particular and what you get out of reading them? I like to seek guidance from dead writers about their attitudes about writing when I’m in a down cycle from my writing.

MS: What a service the Paris Review has done for the world, keeping those interviews going strong! Their range is breathtaking. It reminds you there’s no one way to write. As much as the writing advice, I love the introductions and the circumstances of the interviews themselves. Last night I read the Jack Kerouac. Three poets show up on Kerouac’s doorstep unannounced. Kerouac’s wife, Stella, chases two away but the third talks his way in and the two others join after they promise there’ll be no drinking. What follows is entertaining and disconcerting: part erudite inquiry, part “Shut Up, Little Man.” At one point Kerouac gobbles down pills they’ve brought and only pages later bothers to ask what they were. “Obetrol,” they answer. Kerouac says, “Oh, obies.” I mean, come on!

JA: You have a genuine curiosity about other writers but I’m wondering—and I ask this because I’m doing this panel for AWP next year about professional jealousy—do you ever get jealous of other writers? I mean you’ve sold many many copies of your books, and yet I sense, like any writer, it’s possible to still feel competitive.

MS: I missed the memo on professional jealousy. That must sound easy for me to say because I’ve had a hit book. But even when I had a book that tanked, I wasn’t jealous. Humiliated, hopeless, self-pitying, yes. Maybe I lack imagination, but every time I try to go down the road of fantasizing about possessing another person’s success, it breaks down before I can get off on it. What does that even look like? I’m living my life but I’m writing their books? I was just talking to a writer who was all envious of Jonathan Safran Foer and his expensive house and movie star girlfriend. I said, “You want to move to Brooklyn and live in a giant house and have everyone hate you for it? Where are your wife and kids in this?” I’m sure I sounded like Spock but I couldn’t make it compute.

For those who are jealous of other writers, here’s a hint. Envy is based on your false belief that the other person possesses something magical that exonerates them from the rules of reality. In other words, you’ve created a false construct where you think, “If I had money, I’d have no problems,” or, “If I got a rave in the New York Times, it would wash away the pain of the past, present and future.” Once you realize that problems are an inescapable aspect of reality, envy melts away. Sure, money and fame solve the problems of being broke and obscure. But they come with their own set of problems. Nobody wants to acknowledge it, but good problems are still problems! (Feel free to use that on your panel, Jami. I can come and watch you get booed offstage.)

JA: You sort of grudgingly interact with the internet. It makes some writers feel nervous or annoyed or distracted. I have a very natural attachment to it, even though I acknowledge I spend too much time on it. Is there anything you get out of it?

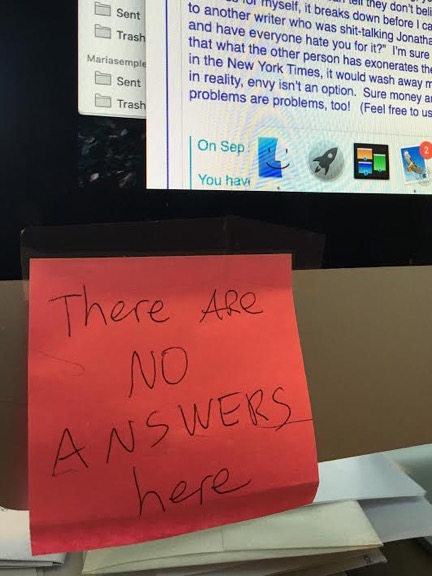

MS: Of course, it’s good for Google and maps and learning how much your frenemy paid for their new house. But here’s what’s taped to my computer…

…To remind myself that if I’m looking for something deeper, I won’t find it on the internet. Obviously there are practical aspects to social media—increasingly so when it comes to book promotion. I have social media accounts so people will know where to find me on tour, and I’m trying my damnedest not to let my pages revert to internet ghost ships. But I don’t talk to people on social media. It reminds me of the time a friend went to see Diana Ross in Vegas. The climax of the show was “Reach Out and Touch.” You know, “Reach out and touch somebody’s hand / Make the world a better place if you can.” Diana went into the audience and implored people, “Come on, everyone! Reach out! Touch your neighbor’s hand!” The whole place was on their feet, people were crying, and Diana walked down the aisle towards my friend, who reached out to touch her and as he did, Diana moved the mic away and said sotto, “I will touch you. You will not touch me.” Then she raised the mic and continued singing.

JA: Oh my god Diana! That’s a scandalous story. You basically mean it’s a one-sided output for you, you have boundaries, walls up.

MS: I don’t have the fortitude for the moment-to-moment verdict of social media. You can handle that, Jami. But it fills me with anxiety and forces me into an obsessive underworld. My way is happily toiling in a cave for four years, hurling my manuscript into the world and running for cover.

JA: I often wish I had more boundaries. I’m trying to get better at it.

MS: In the words of Pudd’nhead Wilson, “It is easier to stay out than get out.” I know I’m defying the basic premise of social media to not be all BFFs with everyone. Publishers stress that readers nowadays want to feel like they’re in a relationship with an author. But I’ve just put everything I know into writing and in exchange you pay me $25 for a book. Can’t we be done?