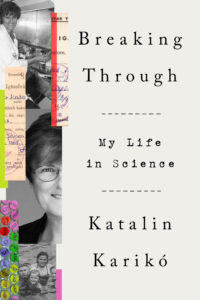

Nobel Prize Laureate Katalin Karikó on Her Hungarian Childhood

“I understand now that this local ‘soap cooker lady’ was the first biochemist I ever met.”

There is a story my family likes to tell: a moment I cannot remember. I am a toddler, still chubby-cheeked, with a blunt blond bob. I am standing in the yard of my childhood home. In front of me, my father has begun butchering the family pig. This is his work, his vocation. He is a butcher. It’s how he earns his livelihood, and it’s how he keeps us alive. He’s been doing this work professionally since he was twelve years old.

The dead animal lies on its back atop a platform of bricks, which keep it from getting muddy. My father singes the fur with a handheld wood burner, similar to a blowtorch. He slices open the long belly of the animal, reaches into the cavity. He scoops out innards, working carefully so as not to puncture the organs. Lumpy intestines glisten. Then he lifts a hatchet and hacks the animal into two equal halves at the spine. Now what lies in front of me seems less like an animal, a being, and more like a product. At last, he begins dividing the carcass into bright red cuts of muscle.

This scene is too much for my sister, Zsuzsanna, three years older than me. Zsóka, as I call her, is not squeamish. This is postwar Hungary, after all. Squeamishness is a luxury afforded to no one—let alone a hand-to-mouth laboring fam ily like ours. But whatever it is that has captivated me in this moment does not seem to have the same effect on my sister.

Still, I am captivated.

My parents used to chuckle, remembering the way I looked then: my wide eyes taking everything in—the whole complex topography of an animal’s interior. All those disparate parts that for so long worked together to keep this one creature alive. All the mystery and wonder they seemed to hold, visible at last.

This, for me, is how it begins.

While I cannot remember those early moments seeing my father work, I recall, precisely, the world that surrounded them, the landscape of my childhood.

Kisújszállás: central Hungary, the northern great plain region. Clay soils. Sweeping grasslands. A medium-size agricultural town of roughly ten thousand people. We aren’t as isolated as some towns; we’re a stop on the railroad, for one thing. Also, Route 4, a primary route to Budapest, goes through town. There are a few paved streets, though my family’s road is made from packed dirt.

Our home is simple, small. It is constructed, literally, from the earth that surrounds it: clay and straw, pressed into adobe walls, whitewashed, then covered with a thick roof of reeds. The reeds, as I remember, have faded in the sun. They look like a shaggy gray wig.

We live in a single room. The house is larger than this one room, but for most of the year, the other rooms are too cold for anything but storage. We live where the heat is. In a corner of the room is the source of that warmth: a sawdust stove, the cheapest possible way to generate heat. It’s constructed from sheet metal, about a half meter across, like an ordinary metal barrel with a central cylinder that is packed with sawdust. We collect that sawdust from a nearby wooden toy factory, carrying it home from the factory with the help of horses. Once home, we store the sawdust in the barn, in a pile taller than my father. In the summer we check the pile regularly to make sure it hasn’t started generating its own heat; sawdust is known to spontaneously combust.

The sawdust stove grows hot enough that my mother sometimes uses it as an extra cooktop. When it really gets going, the exterior metal glows red. Zsóka and I long ago learned to keep our distance, lest we burn our skin. It’s our job, though, to fill the insert container with sawdust every morning. This is hard work, and it must be done carefully. Like many of the things we do, it isn’t a chore—at least not in the sense that people use the word now. It’s not something that our parents ask us to do, not a favor we’re doing for the family. It’s simply what must be done. If we don’t do it, our family will freeze.

At the center of the room is a large table. Here we prepare and eat meals, sometimes gathering extended family for boisterous celebrations. At this table, my sister and I do homework and read, help our mother roll out fresh pasta from flour and eggs.

Each night, my father stands at the head of the table, doling out dinner servings to each of us. He served in the army during World War II and cooked for hundreds of soldiers on the front line, rationing foods with precision. I can still see him today: He ladles pasta into his own soup bowl. “Soldiers during the war on the front lines!” he hollers. Then he reaches for my mother’s bowl. “Soldiers during the war in the back country!” Then he reaches for my bowl, then my sister’s, giving us kids the smallest servings. “Soldiers during peacetime,” he says quietly.

Then he laughs and serves us all a little more. Times might be hard now, but he’s known worse. Every adult has.

Nearby are the beds where we sleep: mine and Zsóka’s, our mother and father’s. The beds are so close, we can reach out to touch one another during the night.

Outside is not only my father’s smokehouse (where sausages hang, dripping thick globs of fat, stained orange from the paprika, onto the floors) but also the barn, where, already, a new pig is growing. Next year’s meat. In the yard, chickens peck the earth, and we have several gardens. In the main garden, we grow food for our family: carrots, beans, potatoes, and peas. Dinner is made from whatever happens to be ready for harvest (flavored, like the sausages, with paprika—always lots of paprika). Zsóka and I have a garden of our own, too. Every spring, we place seeds in the ground. Our fingers are still clumsy, but we are gentle as we work. Gently we cover these seeds with soil, then—weeks later—watch shoots push their way into open air and stretch toward the sun. We also grow fruit. We have apple, quince, and cherry trees, plus a grape arbor and pergolas.

And there are flowers, too: blue hyacinths, white daffodils and violets, and great bursts of roses, which together make this humble homestead feel a bit like Eden.

Someday, decades in the future and an ocean away from here, in a land I haven’t yet heard of called Philadelphia, I’ll settle down in a home on a wide suburban street. There I’ll go in search of flowers to plant, and it is only when I struggle to find white daffodils that I will understand what I’m doing: searching not just for any blooms, but for these, the flowers I knew as a little girl, the ones I can remember my mother planting and tending.

Outside of town lie fields of corn. We plant this corn ourselves, using hoes to soften the soil and cut the weeds. We thin the plants, pull weeds from the soil, fertilize the ground with cow manure, and then harvest the crops. We give the kernels to the animals, then use the cobs to fuel the kitchen stove.

Everything is like that: Nothing goes to waste. We shake walnuts from trees, eat the nuts, and burn the leftover shells as fuel.

It will be years before plastic becomes a part of my life, years before I understand the concept of garbage, the idea that some things are so useless they can simply be thrown away.

We don’t have a cow, but our neighbor does. Every morning, my sister or I run over to the neighbor’s home with an empty jug. We fill the jug with milk still warm from the udder and serve it for breakfast. Leftovers become kefir. When we rinse the last milk from glasses, we pour the cloudy water into a pot for the pig, who devours everything greedily.

As we scurry around, getting ready for the day (the indoor air so cold our breath is sometimes visible), we listen to a small radio. Each morning, an announcer tells us whose “name day” it is. Every day of the year, a different name, a different person in our lives to celebrate: February 19, Zsuzsanna; November 19, Erzsébet. Good morning, the voice on the radio might say. It’s October 2, which means it’s the name day for Petra. The name comes from a Greek word that means stone, or rock. . . . Then, when we arrive at school, we know whose name day it is, and we wish them a happy one. It’s a good system. How many of us really know the birthdays of the people in our lives? But if you know someone’s name, then you know their name day, and can wish them well.

For the first decade of my life, we use an outhouse. At night—especially in winter—we pee in a chamber pot. Nearly everyone I know, at least in these early years, does the same.

There’s no running water of any kind in our house. In the yard, we—like all the families on our street—have a well. Sometimes, I lean over the edge, staring down into the darkness, feeling the cool, wet air on my skin. In the summer, this well becomes our refrigerator. We lower our food to the water’s edge to keep it from spoiling. In the winter months, the whole house becomes our refrigerator (in the coldest months, we store eggs beneath our beds to keep them from freezing).

We use our well water for animals or for watering plants. This water is too hard for bathing and washing, and it isn’t potable, so each day my father walks to a nearby street pump, carefully balancing two thick buckets on a wooden rod. Zsóka and I follow him, carrying water home in smaller containers. Once a week, we heat this water, pour it into a shallow tub, then bathe in it.

At the community pump, neighbors exchange gossip, dis cuss the day’s news, share everyday joys and frustrations. This pump is, for me, the original watercooler, the first chat room.

Occasionally, a man rides up our street on a large horse. He bangs a drum loudly, calling us all outside to hear whatever announcement he’s brought from the authorities. This is another, more official news source—what some communities call a griot or a town crier.

“Next Tuesday,” the man might bellow, “there will be a preventive vaccine campaign for chickens! Keep your chickens indoors on that day so that they each might receive their vaccine!”

We make note of the information, then carry this news to the water pump when we go. Everyone repeats the announcement, in case anyone missed the man’s visit: Did you hear the news? Chicken vaccines. Yes, next Tuesday. Keep your chickens indoors.

And, sure enough, when Tuesday comes, students from the veterinary school enter our yard. Zsóka and I catch our chickens in the hatch and hand them over, one at a time, to the man who will inoculate them—my first-ever vaccination campaign, I suppose.

Science lessons are everywhere, all around me.

I climb trees and peer at birds’ nests. I watch hard eggs become naked hatchlings, mouths wide and begging. The hatchlings grow feathers and muscles, leave their nest, begin pecking the ground. I see storks and swallows take flight, then disappear when the weather grows cold. In the spring, they return and start the cycle all over again.

In the smokehouse, my sister and I collect fat drippings with a spoon. We drop the fat into a pot; when summer comes, my mother calls a woman to the house. She’s ancient, this woman, carrying knowledge passed down through generations. Under this woman’s direction, we melt the fat, then mix it with sodium carbonate, using a precise ratio she alone seems to understand. Then we pour the mixture into wooden boxes padded with a dishcloth and wait for it to harden into soap, which we slice with a wire. We use soap bars for bathing and shave some into flakes for laundry.

Looking back, I understand now that this local “soap cooker lady” was the first biochemist I ever met.

Science lessons are everywhere, all around me.Another lesson: One summer, our potatoes are infested with a pest, Leptinotarsa decemlineata, known in the United States as the Colorado potato beetle. The insects lay eggs, and larvae explode across the garden, eat away at stems, and turn entire leaves to lace. They’ll destroy the whole crop if we do nothing. My parents put me on potato beetle duty. I scour the plants, plucking insects one at a time, dropping each into a pot. Each bug is about half an inch long with a spotted head and dramatic black and white stripes on its backside. The bugs themselves don’t especially bother me, but when I miss one, it lays clusters of eggs, from which erupt disgusting pink larvae, wriggling and sticky. I pluck those, too.

The work is tedious and sometimes gross. But it provides me with an early education not only in entomology but also in ecosystems. For here, too, nothing goes to waste: I feed these pests to the chickens, who are delighted with the bounty. Potato beetles feed the chickens, who in turn feed us: a lesson in the food chain that becomes, quite literally, a part of me.

There’s no end to the work to be done. My sister and I carry water to chickens and gather their eggs. On the rare occasions when our family chooses to cook one of our precious chickens, we chase that bird down with a broom and scoop it up. We wash dishes and clothes by hand. Twice a week, my grandmother, who lives a half-hour walk from our house, cuts bunches of flowers from her garden—labdarózsa (snowball bush), török szegfű (sweet Williams), rózsa (roses), dália (dahlias), szalmavirág (strawflowers), tulipán (tulips), kardvirág (gladiolus), and bazsarózsa (peonies)—then hauls them to sell at the market. We help her cut and prepare these flowers for sale.

Even if my grandmother hadn’t told me the names of these flowers, I would have learned them by heart. In fifth grade, I receive a book about the flora of Hungary; the book features gorgeous watercolor illustrations by Vera Csapody, a Hungarian woman botanist and artist. I am obsessed with this book; hour after hour, I turn the pages, memorizing the bright bursts of colorful petals, the spindly root threads emerging from rotund bulbs, and the precise variegations and striations of leaves.

__________________________________

Excerpted from the book Breaking Through: My Life in Science by Katalin Karikó. Copyright © 2023 by Katalin Karikó. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.