am weirdly politically correct"">

am weirdly politically correct"">

John Waters: "I think I am weirdly politically correct"

Alexander Chee in conversation with the "Pope of Trash"

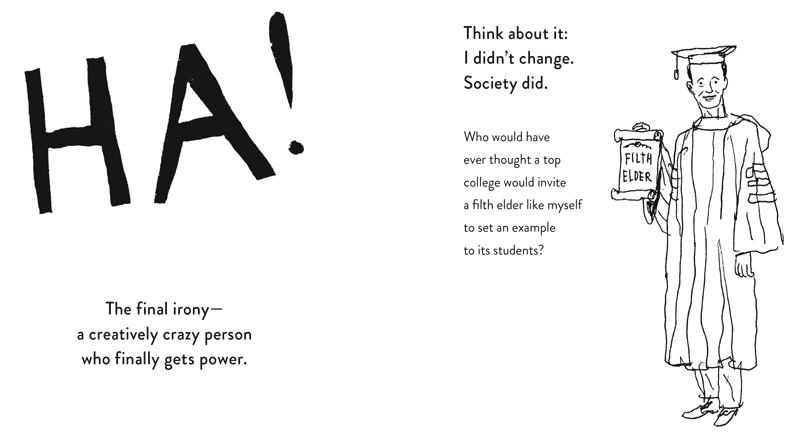

Not quite two years ago, John Waters, the legendary filmmaker, writer and self-described “filth elder,” had a viral moment (of the good kind)—his 2015 Rhode Island School of Design commencement speech, in which he playfully encouraged the graduates to make trouble, was everywhere. It was reprinted countless times across many platforms and turned into listicles—“Nine Takeaways from John Waters’ Graduation Speech”—and really, while this is all well and good, it’s always better for the artist to get paid. Now the speech is a beautiful gift book you can give to your favorite graduate, or yourself, this spring: Make Trouble, just out from Algonquin Books.

Waters took some time out to talk to me about the speech’s genesis, his filth elders, making art, whether or not one needs talent, Trump (just coincidentally), and political resistance, of course.

Alexander Chee: I enjoyed the book a great deal, and I enjoyed the speech at the time that it came out. Were you surprised that it went viral, or did you write the speech and think that’s a really good speech?

John Waters: I have a spoken word show, so I live on the road speaking to colleges and young people. I have a show called “This Filthy World” I do in theaters everywhere, so a graduation speech is not that different from the kind of thing I do anyway. I read it to my friend the night before, and he said, “I don’t know, you might want to ask a couple people.” Which made me laugh, but I’m used to that reaction; it can go either way. The reason anyone likes it is because it’s not that normal, and when I gave it, I could hear people really laughing. When the graduates would walk by me—all 800 of them, each one gets their degree after it’s over—a couple of them said, “Wow, that was amazing.” And I could hear the parents really laughing, but I was surprised at how far it went online, and then I was even more surprised when it became a book. But I’m an optimist; I think everything’s possible. Or else how would I have ever started making movies with my friends in Lutherville, MD? How could anything have ever come from it?

AC: And that guiding spirit is in the book as well.

JW: It might be, it might be.

AC: I loved this idea, in the book, of the “filth elder.” Do you have filth elders that you have in the back on your mind?

JW: I think my book Role Models was about all of them, really. It was about the people that give you the confidence to become who you want to be. It is always things that happen to you when you’re young, I think—being a filth elder to other people, I’ve certainly had people come up and tell me that, and it’s certainly a compliment. And I think I have made people feel better about themselves. I think I am weirdly politically correct, even though I say things that could have put me in prison. It is amazing that we have a country that is free, because I can make jokes about Pence shaving his balls, and I don’t fear yet that I will be arrested. But I gave an interview in Russia the other day, and I thought, what can I say here? I don’t want to get them in trouble.

AC: That’s sort of for that publication to take care of, thankfully—

JW: It is. I said, “I hate the leader of your country and mine.” Whether they’ll print that I don’t know, since it was a film magazine. I didn’t get final edit.

AC: With the idea that wisdom is born out of great mistakes, are there certain mistakes you made that went into the wisdom that became this speech that became this book?

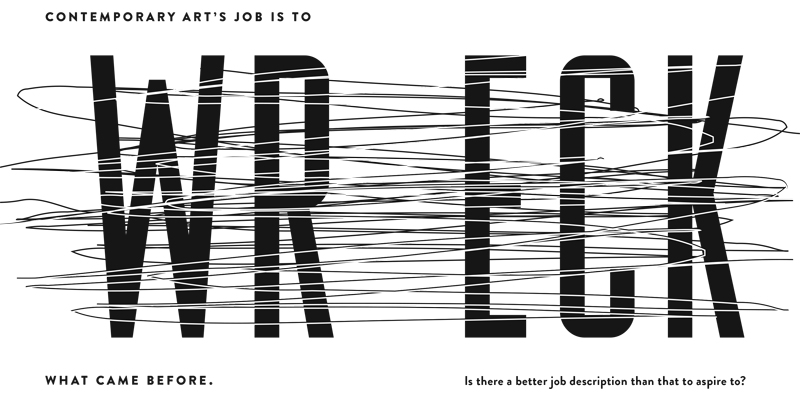

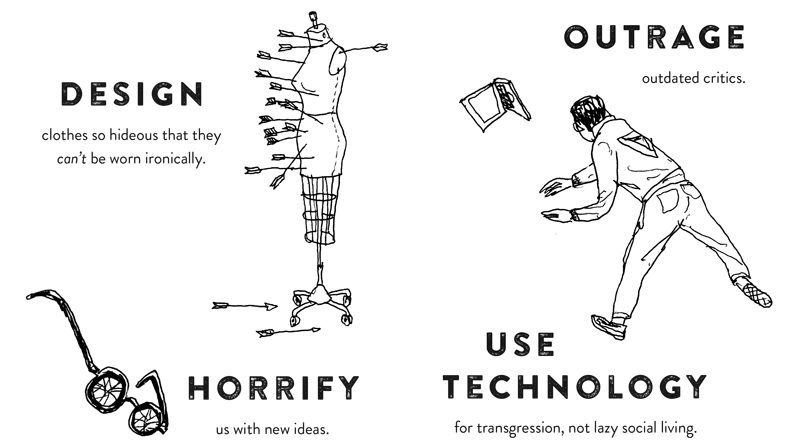

JW: I didn’t call it wisdom, but thank you. The mistakes I made were technical mistakes. If you approve of those mistakes, you call it arty, and if you don’t approve of them, you call it amateurish. It means the same thing. I have a line that Cecil B. DeMented said: “Technique is nothing more than failed style.” In a way, I believe that. My early movies, like Multiple Maniacs, which came out recently and, for the most ludicrous reasons, got the best reviews I’ve ever gotten in my entire life—which I even find preposterous—just goes to prove that.

At the same time, I don’t think I made mistakes, because I never thought I’d get as far as I have. Everything that’s happened to me in the past 15 to 20 years is complete gravy. It’s beyond what I’d ever had hoped for. I’m very thankful that I always had an audience—I’m not saying every movie I made was a success at all—but I don’t have anything to complain about, certainly. If I made mistakes, it was just learning how to get in further, how to get beyond them—this didn’t work, so let’s try this. That’s what I say in the book. No one’s free. You cannot fear rejection if you’re going to be in show business because it’s a life of rejection. That’s why when you’re young, bad reviews don’t hurt, because you’re just glad you got reviewed, that someone noticed it. They hurt when you’re older because then you have something to lose.

AC: That’s easily the most interesting point about living out past the edge of what you imagined for yourself. And I think that’s part of what your book is urging people to do, to say, “maybe you haven’t thought far enough.”

JW: When people come up to me and say, “How can I be a filmmaker?” I say, “Well, you won’t be. Because there’s no easy way or every person in America would be a filmmaker.” What a good job! You get paid well and tell people what to do all day. You have to say, “I’m gonna do this, and would this work, would that work?” But the thing I talk about in the book is, so what if you have talent? The other half is what to do with it. You have to learn the business, you have to learn to thrive in whatever business you are trying to enter. The arts is still a business, pretty much. No matter what it is, you have to get people to like it, you have to get people to see it, so you have to understand the business. You have to participate in the business you’re trying to enter. Don’t tell me you’re an artist and that you don’t go to any galleries. Don’t tell me you’re a filmmaker and you don’t care if anyone sees your movies. Well, no one will.

AC: One of the things that I really enjoyed about this also is how you inverted the outsider fantasy, which is like this thing that rules American politics, American arts. Instead, you tell us to be the ultimate insider.

JW: Don’t both Obama and Trump believe they are outsiders? It is a word that has lost its punch. “Insider” is much more threatening.

AC: I wonder if you could expand on the moment you realized that.

JW: Hairspray helped me realize it a lot because it snuck into Middle America when I never expected it to. It has the same values that I’ve had in every one of my movies—there are two men singing a love song—and yet they do it in college now. Even Republicans like Hairspray. I remember George and Barbara Bush went to see it, and he was like doing the twist out front, and I thought oh my god, what have I created here?

AC: Talk about living past the edge of your imagination!

JW: Even Republicans, teabaggers love Hairspray. Which is kind of the ultimate crossover, if no one notices that the work you did is against their values and they embrace it. Isn’t that a sneak attack? That’s like terrorism. The good terrorism.

AC: Spiking the punch at the party and making sure that something better happens.

JW: You can only change somebody’s mind if you make them laugh first. You get up and preach and preach and preach and nobody want to hear you, including me.

AC: And that’s an interesting and wonderful piece of advice. Of course, everyone now is wondering what happens to us now in the era of Trump. And this advice book—is it an advice book, exactly?

JW: I guess it is a self-help book. But all my books are self-help. Just call me Norman Vincent Peale on the down low.

AC: How do you feel like this stands up in the age of Trump? Do you feel there are any ways it needs to be finessed?

JW: No, I think actually—because when I gave this speech no one, including me, imagined Trump would win—it makes it better. It almost seems like it was written in reaction to that, which was completely accidental. At the same time, Make Trouble… isn’t that a pretty good title for exactly what everybody should be doing today?

AC: Of course, now I’m having this fantasy of you making a Trump biopic.

JW: No, I would never, because you date it. I’m writing a book right now; you never put in a Trump joke because you date the book. Every day, he says something more stupid. All my books are still in print—even the first one that came out in 1980. If I had a joke that was that specific, then it wouldn’t last.

AC: That’s an excellent point. What does this phone call find you writing now?

JW: I’m writing two books for FSG. The first one is called Mister Know-It-All, which is detailed essays on how to avoid respectability at 70, and then after that one is done—and I’m about halfway through that—I’m writing a novel called Liar Mouth about a woman who steals suitcases at airports.

AC: You said you’re about halfway through the first one; when should we look for the second one?

JW: Oh, the second one, god knows. I’ve got homework for the rest of my life. That’s what a book advance feels like. Homework. Paid homework.

AC: Were you someone who wanted to be a writer when you were younger?

JW: Yeah, I wrote movies, I wrote a story called “Reunion” when I worked at a camp when I was 13 years old. It was a horror story with gore and everything, and I read it to all the campers and they all freaked out and had nightmares and the parents called the camp and I got in trouble. That was the first thing I ever did with writing. The second thing, I published something in Fact Magazine—Ralph Ginzburg’s magazine—that was totally not a fact; I made it up. I had a reputable beginning in publishing.

AC: Do you remember what you made up?

JW: Oh sure, it was called “Inside an Unwed Mother’s Home” by Jane Wiemo. J-W—get it? I guess it’s my drag name, my pen name. It really did happen to a friend of mine, but Fact Magazine based the whole thing on that it was completely true, and it was sort of true.

But now my books are true. They’re fact-checked.

AC: Is there anything you want to add?

JW: College students, stop studying, get out in the streets! You had one march, big deal. Resist means you don’t just sit there and do homework when we have him as president.

AC: It’s really true.

JW: Every day, there should be a march.

Alexander Chee

Alexander Chee is the bestselling author of the novels Edinburgh and The Queen of the Night, and the essay collection How To Write An Autobiographical Novel. A contributing editor at The New Republic, and an editor at large at VQR, his essays and stories have appeared in The New York Times Magazine, T Magazine, The Sewanee Review, and the 2016 and 2019 Best American Essays, among others. He is a 2021 United States Artists Fellow, a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in Nonfiction, and the recipient of a Whiting Award, a NEA Fellowship, an MCCA Fellowship, the Randy Shilts Prize in gay nonfiction, the Paul Engle Prize, the Lambda Editor’s Choice Prize, and residency fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the VCCA, Leidig House, Civitella Ranieri and Amtrak. He is a professor of English and Creative Writing at Dartmouth College.