It Breaks Before it Bends: On Donika Kelly's Black Girl Poetry

Nikky Finney in Praise of a Psalm of Pure Resolve

A first book is a migration story. It is a leave-taking from the old rules and rulers. Turn. Rotate. In this migration story, a poet returns west in order finally to set sail. There is death in the home-going. There is sweet birth. Opening the wide door wide will require a hammer of words.

The poet learns what trust is and isn’t. What real is and what real isn’t. A liquor store and a beauty shop are on fire behind her. The poet can smell the pomade and the alcohol burning together. She whistles and crows as she gathers up everything she can. We follow her because the suitcase she is holding is smoldering with all of us in it. She stands there holding on tight to the grip’s hot handle. We read and blow on our own fire-eaten hands as we turn. Keep turning. The screen of pages, as you will see, keeps changing from little girl on fire to burning ancient Los Angeles, to sex. She will not look away anymore. The poet who is writing of the narrator’s undoing has refused to be undone and disappears somewhere into the ink without warning. Turn.

I found the first book of Donika Kelly’s poems to be made of red bricks and seashells, poem material so old you can still smell the salt in them—from before—when the city the poet is returning to was not a city at all. Some of the poems sit squat in the middle of the page like something you could throw and break a window with. Some of the poems fall down the page like the ladder required to climb inside that broken window. There is always the glimmer and glint of hope in these poems peering out, even as the page smolders. On the map itself, there are places where blood has been spilled. There are places where screams went ignored. Rotate. Turn. See the daughter finally stop running from herself.

Keep reading and you realize this poet rests her alphabets in the mythology of fire and the resurrection of ecstasy. She is gripped in a blaze that has never gone out, that has continued to burn underground, in the safety of a daughter’s only, orange-light horizon. See the mother. See the resurrection. Move on.

The poet has decided to run into the many rooms of memory. She has clearly drawn her weapons. She knows trees: fig, walnut, and olive. She knows birds: blue bower, cave swallow, hermit thrush. She knows Greek mythology. A minotaur can sometimes be seen running outside the window. The minotaur keeps up with her Black girl life.

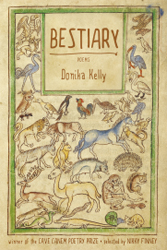

Bestiary is a first book of poems by an all Black girl who teaches us nothing is all black, or all female, or all male, or all belonging to humans, or all tidy. Bestiaries come out of an old tradition, but the beasts that push us to write our modern migration stories are found everywhere we dare deeply look. A hybrid of longing and lust is chronicled and mapped out here. What has been made contains a compass of new measuring. An inch is now a foot swinging at the father’s head.

Before it is over and the last page turned, we will discover that the poet is not afraid to close her eyes around every winged thing she can find. We will see she has great need of elevators and anything else that will lift her from the ashes. Levitation. Rotation. Landing. She walks strongly and confidently, right up to the live thing, and then pushes her tongue deep into the skin of a patch of black walnut trees in order to hear what she really needs to hear. She is measuring out what she needs in order to leap.

There are hundreds of years of unreliable others imagining and appropriating the desires of Black girls, eschewing their hopes and dreams as poets and people.

Kelly’s first poetic report to the world would not be complete without including the national-pastime party drinks of Black people: pink panties, screwdrivers, and that smoothest of smooth operator, Canadian Club. Reverence is held onto for that most sacred Black card game, Spades, the one that is tattooed on the back of every Black person’s hand born before circa 1980. Rotate. Turn.

The official public record tells us there are hundreds of years of unreliable others imagining and appropriating the desires of Black girls, eschewing their hopes and dreams as poets and people, their birth-marked stories, their personal migrations. For the other record, let me say, those reports have never had anything to do with Black girls and whales, Black girls and riots, Black girls and minotaurs, centaurs, satyrs, mermaids, werewolves, or Black girls “being a thing that breaks before it bends.” Black girls have always and often been the whispered-about and the strangely labeled. Not enough Black girls, whose own personal stories could turn you to stone with just a whisper, their up-the-side-of-the-mountain migrations rarely published or allowed to be told. But here is one that I have pulled from the great pile into the light so we might add it to the small truth pile of others. In Bestiary, no bending will be allowed. Rotate.

Kelly catalogs the scribbling girl heart switching and swooning, sweating, remembering, chiseling—memories cradled upright into the unholy light of childhood’s LED lights. A migration of pure trust. The poet finds the cadence and courage to morph into wired-hair, mythical Griffon, the pointing dog known for its even temperament, rough coat, and bearded muzzle. Turn to midnight, turn to the father who is also there at midnight, “walking from his room to mine,” after which the poet begins whistling—and crowing too. Rotate. Turn. Remember the old churchwomen who twisted our ears and warned us about “the whistling woman and the crowing hen?” How righteously they dangled that stand-alone brazen woman before our eyes, believing that if they did we might be scared enough to be “good girls” and stay in line. Remember how they warned us we would come to No Good if we followed the whistling crowing woman? Please follow closely.

Come inside. Kelly’s first book is a compendium of rocks, ledges, whistles, and edges. These poems come complete with their ithyphallic males, with their eye-to-eye looking at each other and their permanent erections. Kelly introduces a human obsidian cast of characters, alongside the poet’s bright-speckled granite memory, spilling with nests made of translucent stones, blood, and floating feathers from the long, preening migration journey of girl to woman. Harder things are held high. There are also the brutal, bruising, unexpected drops straight down.

In order to find comfort or truth, or both, we are not allowed to leave the poet’s journey too soon, not before the narrator takes the time to see herself as a serious student of male porn, “Only the boys for me now, hard / bellied and fucking.” A narrator who loved cartwheels and was always afraid of riots and the Pacific air on fire finally makes it to the land of her birth, turning her own intimate pandemonium into olive trees, turning the fires on the edge of town into the mating call of the whistling female thrush. Looking it all right in the eye.

Donika Kelly whistles and crows her book into a psalm of pure resolve. And in the end, no mythology remains. Everything is singed and true. A report has been filed on the poet’s behalf. A Black girl has whistled and warbled into the morning and night air and dutifully weighed in with her long black pen. A new song has been measured out from the ancient rubble of Los Angeles and the poet’s own four-chambered muscle. Bestiary’s lesson is complicated and also simple. Love can be hunted down.

From the introduction to Bestiary. Used with permission of Graywolf Press. Copyright © 2016 by Donika Kelly. Introduction copyright © 2016 by Nikky Finney.

Nikky Finney

Nikky Finney is the author of four books of poetry, On Wings Made of Gauze, RICE, The World Is Round, and Head Off & Split, which won the National Book Award for Poetry in 2011. She has written extensively for journals, magazines, and other publications. For 21 years she taught creative writing at the University of Kentucky and now holds the John H. Bennett, Jr., Chair in Creative Writing and Southern Letters at the University of South Carolina in Columbia.