Is Pedantry the Mother of the Essay?

And Other Questions Ken Chen Has for the Essay at the End of Time

The following is from How We Speak to One Another, a compendium of writers in conversation with and about essays of any kind, contemporary or classic, drawn from Essay Daily.

[A white screen]

Q. You! I knew you could procrastinate, but this book is nearly going to press, and you have still not started your essay. In fact, you have procrastinated so much that you now write this essay at the end of time itself!

[Camera opens upon a dystopian tableau (the heat death of the universe, to be precise) and pans toward the author of this essay, who is sitting at a desk garlanded by cyborg wires and extraterrestrial meshes, clearly technology thousands if not millions of years into the future. In the window: Star Trek: The Next Generation-style starscapes, Dyson spheres, hawkers selling End of the Universe merch.]

A. [A wobbling cigar clenched in jowl, the writer bangs his palms against the keyboard—faux-typing as Art Tatum percussionist tantrum.] I am writing! Can’t you see I am writing!

Q. [The interviewer floats as a disembodied ai consciousness, she (or rather it) materializes a goblet of sherry via the nanotech hospitality services. The sherry levitates in the air and slowly vanishes, so as to mimic imbibing.] I have to admit that I am surprised—you are not unfamiliar with secreting out ideas at the behest of the suspenseful cliff-hanger, but now you have taken your belatedness to an absolute level. We scarcely have a few minutes before all the space-time around us collapses. Will you make your editorial deadline?

A. [In a leisurely tone] To be honest, perhaps I was set back by the prompt: to write about one essay. I think I felt suspicious about that directive, a suspicion that when coupled with my aura of cognitive turpitude proved entropic. Though I hold in my hands the very essay about which I am writing an essay. [Fans himself with a sealed envelope in the air, a la the Oscars.]

Q. Suspicious? Why would it be suspicious to write about essays?

A. Not essays in the abstract, not essays in the multitude, but about one essay, the essay, the definite article. [Outside, a few of the stars begin to shut down, the fuses of old bulbs buzzing off. The universe is leaking its variety like a bad anthology.]

Q. I see! Might as well write about a food you ate, that one time!

A. Or your favorite breath of air! Your favorite attempt! Your favorite excuse! Your favorite procrastination! [Flapping the envelope around, he accidentally flips it into the air, where it wafts and lands behind him.]

Q. Aren’t you being a little . . . pedantic? You could surely name a singular example of other things with which you possess a similarly polygamous relationship (say, your favorite book), could you not?

A. Is pedantry the mother of the essay? In addition to the word no, the obvious difference is that the book is an aesthetic object. [Looks confused, then gets on all fours to look for the envelope.] What would it mean to consider the essay into an aesthetic object?

Q. Is it bad to be an aesthetic object?

A. You should ask a woman.

Q. An essay is not alive.

[Is the essay alive?]

A. [Stands up, holding the envelope, brushes dust from knees.] I call it “Casper.”

Q. What are you talking about?

[To disembodied intelligence] Are you Casper?

Q. Who is Casper?

A. The aesthetic, the imaginative, etc.—a cute cartoon of make-believe!

Q. [Laughs]

A. [In Old Testament jeremiad setting] When the essay believes it has achieved autonomy, what it has gained is not sentience, not a modernism or avant-gardism. Rather, it has become cute. Essay anthologies rarely include, say, lies, prayers, liturgies, scientific treatises, pamphlets, non-stylized journalism, movie reviews, philosophical theory, scholarly encomiums, or my receipts. I need the receipts to get reimbursed for my plane fare to the end of time–

Q. Is a newspaper an aesthetic object? Also, are you going to open the envelope now?

A. That the newspaper would never be aestheticized (except perhaps now as a physical object of nostalgia) is my point. You would never select your favorite issue of a newspaper to anthologize. The newspaper occurs inside a print culture, a context of news and politics, time and space. [Holds out the envelope and begins to open it, but then relents, realizing something with a sigh.] But I anticipate what you are saying. You are saying I barter in false analogy.

Q. Is the essay a newspaper?

A. Well, one rarely learns from the contemporary essay because there is not enough world to go around. The literary essayist is ashamed of the barbarism of pure content and so turns her own genre into a pop-up book, for example, through embarrassing formats like outlines and lists and faux-interviews.

Q. I see. Or the exception that proves the rule is when the essay (that most maximalist of genres) becomes assimilated into a nonfiction wing of the novel through creative nonfiction and memoir.

[Gulp of sherry.]

A. See, if our conversation were a literary essay, I would write it as an essay progressively getting drunker.

Q. Is not the essay different from those other genres in kind? Or do you see all prose nonfiction as equal?

A. I hope I do not simply palm one gauche purity and substitute an even less polluted impurity. First, more than any other literary medium, the essay possesses an unusual function—that is to say, it possesses a function. Many essays can be right or wrong. And they can possess means by which to be morally or politically accountable. Can a poem be right or wrong? Second, the essay possesses a more direct and unmediated relationship to content. The novel and the poem gaze at the actual world through a lens that has been greased with auteurship, non-argumentation, and fictiveness. The aesthetic is that which possesses no function or content—the beautifully useless. When we aestheticize the essay, we staunch its utility and its reality. The literary essay rarely includes criticism or scholarship, since both possess an object and the literary essay must be its own object. The aestheticized essay is the fossil text—the essay at the end of time.

[Why does science fiction’s vision of the future not more often include literary critics?]

Q. Aesthetic as anesthetic! You fear that the genre-fication of the essay represents its gentrification. I can prove you are wrong. I shall do so relying on utterly trivial facts that contradict you in my utterly inventive fabulous forthcoming essay!

A. Do your made-up facts have good or bad politics? Do they come with a cost?

Q. I will make up facts with good or bad politics! I will make up an imaginative cost!

A. [Cantankerous, shoos away bodiless, noncorporeal entity with the envelope.] Shoo, the aesthetic, scram you smug mildew, you Casper the friendly ghost!

Q. I suspect something perhaps more and less profound: you are afraid of vulnerability. You do not want to be pinned down. You would invent whole political ideologies and speculative futures before being caught doing something as tacky as loving something—or exposing yourself by naming a single essay you like.

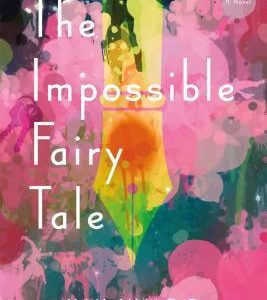

A. While my self-loathing tempts me to agree with you, perhaps the best way to rebut you is by praise. Lately, I have found my favorite prose nonfiction writers to be academics or radical writers like Michael Denning, Katherine McKittrick, Amitava Kumar, David Graeber, Sianne Ngai, Bhanu Kapil, José Rabasa, Benedict Anderson, Jacqueline Rose, Pankaj Mishra, Cedric Robinson, Timothy Mitchell, Fred Moten, and M. NourbeSe Philip, whose epilogue in Zong! is the best essay I have read this year and maybe the best essay I have read on the process of writing.

Q. Hmm . . . I’ve never heard of them. Do they write short elliptical fascicles? Do they embed actual text messages into an otherwise fictional narrative? Have they ever written a poignant personal reflection in a Choose Your Own Adventure format?

A. No.

Q. Oh, too bad they are not imaginative writers.

A. They are very imaginative writers. They have imaginative politics.

[He sits on the floor in front on a steel-colored pillar constructed from (insert technobabble). Thinks about Nietzsche’s comment that Plato’s fake plays were the lowest mode of adversarial sock-puppetry.]

Q. [Awkward disembodied yawn] When you are bored, do you try to fill it with essay?

A. What is it, is the question I guess. [In a way that is impossible to represent visually, the disembodied voice stares outside the window at gray goo floating through the sky like lazy plankton.] I am not bored. I am annoyed.

[What would it mean for film to exist at the end of time?]

Q. You have changed, you know, in the ten trillion years that I have known you.

A. Have we really known each other that long?

Q. Yes, I am the computer, the you-computer, you installed in your head to eject you from your head when you feel like your ghost is evaporating out of your skin. Do you think you have changed?

[Ken Chen was born in San Diego, California, in 1979 to two Taiwanese immigrants who had come to the United States on the planet Earth. A resident of New York, he uploaded his consciousness in the sixteenth millennium and became a roaming nebulae when–]

[So you are saying he is a gasbag filled with hot air.]

A. When I think about the eons that the multiverse has expanded and contracted its vast caverns of space, I think about all the people I have known and loved. I think about how these experiences have changed me. One way that I have changed is in my relationship to the essay.

I used to love the essay for its discursiveness. It is a seismograph of a consciousness trawling through the language. An essay, you see, is a style of thinking. The idea of an exceptional essay insults this idea, curating an exemplary product rather than viewing any given essay as a trace imprint from a larger consciousness. I once found myself comforted by the power of essays to explain—to get a wee bit sentimental, the way they inadvertently act as wisdom literature.

Lately, I find myself wanting art that knifes away the subtitles.

Q. Is our conversation an essay? [Pause.] No response?

A. [Checking phone.] Sorry, people I have never met are congratulating me on LinkedIn for an anniversary of which I lacked awareness.

Q. The return of time! Do you believe that prepositions shouldn’t be what your sentences end with?

A. If a preposition expresses a relation, what does it mean to end on that relation—on the interval?

[Are stage directions the comment code in the programming language of visual narrative?]

Q. I think you have procrastinated to the end of time, because procrastination is the most essayistic endeavor, and because now that we are at the end of time, we have access to every essay that will ever have been written.

A. I do not like that quantitative and commodifying approach to human noises [reaches for a spray canister of Borges Repellant], but shall I talk about an essay I’ve been thinking about lately?

Q. You’re kidding!

A. The Communist Manifesto! You’d never see it in an anthology of literary essays despite it being the most influential essay of the last two centuries.

Q. You don’t even like it.

A. The essay I would like to talk about is–

Q. Do you believe that essays are how we speak together? Or more to the point, why are you being so sophomorically antisocial, so unhelpful in this essay?

A. Wait, where did I put that envelope?

Q. That flimsy and renewable source of narrative?

A. Wait, something’s coming to me. [Suddenly the camera shakes, and the two players wobble and grab the furniture melodramatically.] What was that?

Q. This platform is reversing direction.

A. [Outside, black holes expand and resurrect into bloated red giants.] So I’ve been thinking lately of this poem I once read in elementary school. [His interlocutor watches the author stare out the window with an autumnal air of wan remembrance and begin to whisper what sounds like the word, Rosebud.]

I don’t remember the name of it. The poem was about this little boy in caveman times. It was about, like, you know, how he’d whip a snake as a lasso or wash himself using a woolly mammoth snout as a showerhead. I once pictured my younger self reading this poem as a young and future poet being struck by the magic of metaphor. Now I realize that what struck me was something more prosaic–

Q. Ha ha.

A. My liking the poem actually betrayed an essayistic tendency. The poem was speculation. I liked the poem because it expressed an idea one could paraphrase, somewhat like an essay, rather than because it made me experience a narrative (fiction) or the materiality of language (poetry).

[Hi, guys!]

Q. You have been quoted in the interstellar transmat media saying that you wish to swallow up poetry and the novel as subgenres of the essay.

A. They have proven rather tough gristle.

[Outside, all matter begins to heat up and swirl. Planets become hot dust.]

Q. What are you doing as you are writing this essay?

A. I am hunched standing at the kitchen table while my daughter Leila plays by herself on the floor.

Q. How old is Leila?

A. She turned fourteen months yesterday.

Q. Through what fourth-dimensional flux can you exist in such separate times at once?

A. The technology of lies, love, and the essay.

Q. What is happening?

A. We have arrived at our end, the beginning of time.

[A white screen]

“Is the Essay at the End of Time?” is reprinted by permission from How We Speak to One Another (Coffee House Press, 2017). Copyright © 2017 by Ken Chen.