How Lewis Michaux Channeled a Passion For Knowledge Into Building His Harlem Bookstore

Vaunda Micheaux Nelson on Her Great-Uncle's Contribution to the Intellectual Empowerment of Black Communities

“Knowledge is power! You need it every hour! Read a book!”

“If you don’t know and you ain’t got no dough, then you can’t go and that’s fo’ sho’!”

With words like these, how could I have resisted falling under Lewis Michaux’s spell?

I believe books saved my great-uncle Lewis. As a reader, librarian, and writer, I was drawn into his story.

Lewis was independent-minded, some might say stubborn, from the time he was a child. As a boy, he refused to work in the fields for twenty-five cents a day. Instead, he found more profitable, sometimes illegal, ways to make money. Lewis’s self-directed nature may have led to dangerous risk-taking in his youth, but it served him well when he found his calling in books.

I did not experience the kind of troubles Lewis had growing up, but, like him, books were crucial in the making of me.

My early inspiration to read and write came from my parents. They read to me and my four siblings every night. Most times my mother read the next chapter of our current book, but sometimes Dad would recite poetry from memory, some his own.

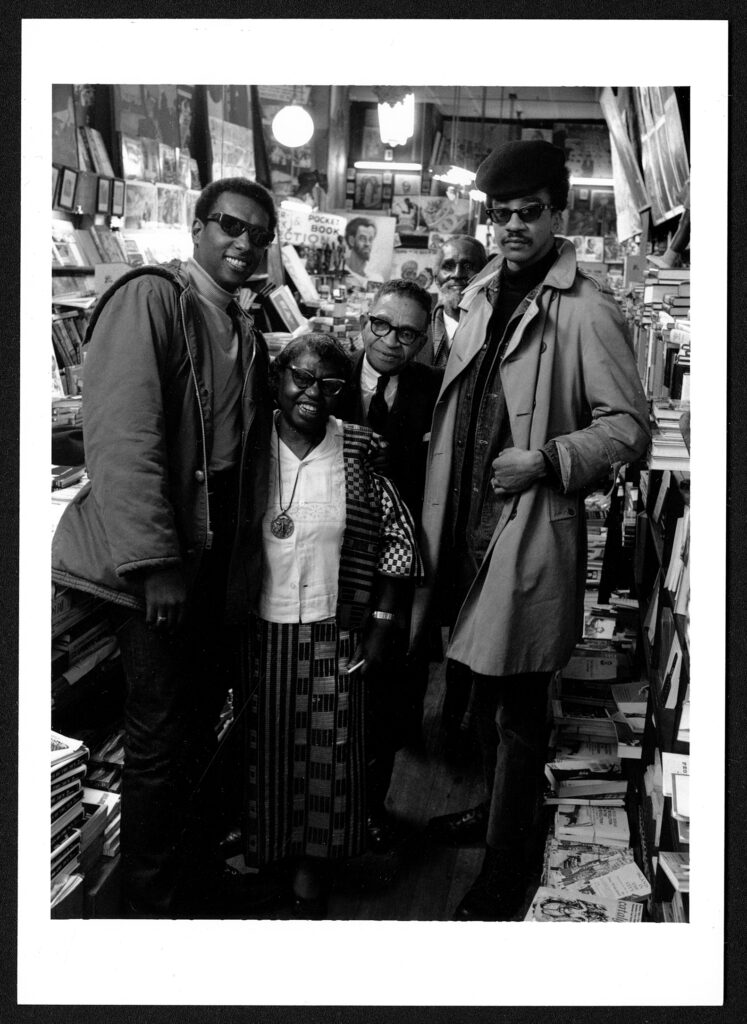

James E. Hinton. “Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown in Michaux’s Bookstore in Harlem, 1967.” Courtesy of Emory University Rose Library.

James E. Hinton. “Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown in Michaux’s Bookstore in Harlem, 1967.” Courtesy of Emory University Rose Library.

My parents gave me their love of stories. And they taught me the power of words—how they can lift up and tear down—“so be careful with them,” they said.

Lewis’s self-directed nature may have led to dangerous risk-taking in his youth, but it served him well when he found his calling in books.

Thanks to my older sister, Regina, when I started school at the age of five, I could read. The ability to read gave me more access to the stories my parents had inspired me to love. Reading led to writing; the rest is my life.

Knowing what I know now, I have no doubt that my father’s love of literature, particularly poetry, was encouraged by his uncle Lewis. My mother, who worked in the bookstore before marrying my dad, most certainly caught the fever as well. I may owe Lewis more than I know. It’s possible that I am a writer today because of his distant influence.

Lewis once said, “Where did I get that literary idea? I could have been an iceman.”

How providential that he was not.

*

In 2012, after years of research, I published No Crystal Stair, a documentary novel about my great-uncle. The book contains the stories of those affected by Lewis, by his simply saying, “Here are some books about you.” These vignettes, based on what I learned from and about actual patrons, are only those I could uncover—surely it’s just the tip of the iceberg.

It seems wherever I go to speak about Lewis and the National Memorial African Bookstore, someone stands up and says, “I was in that bookstore!” Who knows how many more are out there?

Lewis Michaux spent most of his adult life working to provide books by and about black people and encouraging them to explore their history and culture, to give them a sense of pride, to empower them. Frequent bookstore visitor A. Peter Bailey put it this way: “When I’m there, I don’t just read. I listen. I listen to Brother Michaux talking about the books and current events. He and his peers are like older brothers to the rest of us. They discuss issues and argue. I just stand around and get free history lessons.”

Lewis was a self-defined man, and he wanted black people to define themselves, not be defined by others. He believed books could provide the knowledge and language to do this. He never tired of stressing the power of learning. “You gotta know who you are before you can improve your condition,” he said.

Lewis’s words, his definitions, bored into me, turned me around and upside down, tripped me and flipped me.

He said, “I am not a so-called Negro. I say ‘so-called’ because a Negro is a thing, not a person. The word is an invention. A Negro is a thing to be used, abused, accused, and refused. That’s his role in this stroll. And blacks who continue to accept this ain’t going nowhere.”

He took my breath away.

I hope those who learn Lewis’s story will be left with a deeper desire to know more, to learn more, to question, and to be informed enough to avoid allowing others to decide who they become.

Lewis said, “Knowledge is the thing today that is needed among the young people.”

I hope those who learn Lewis’s story will be left with a deeper desire to know more, to learn more, to question.

He cautioned, “You can’t protect yourself if you don’t know something.” I love what he’s saying here. You can’t protect yourself if you don’t know something. I wish all young people could take this to heart.

Lewis determined that reading was good for him, and it would be good for other striving African Americans. He believed who we become depends a great deal on our desire to be educated, our efforts to know our history and ourselves, and our resolve to contribute.

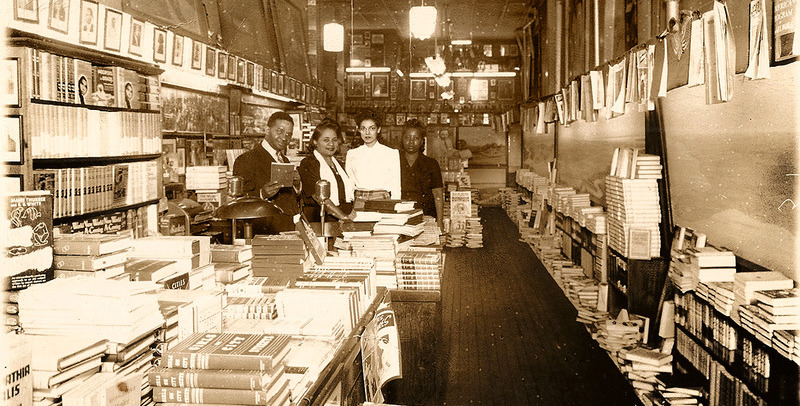

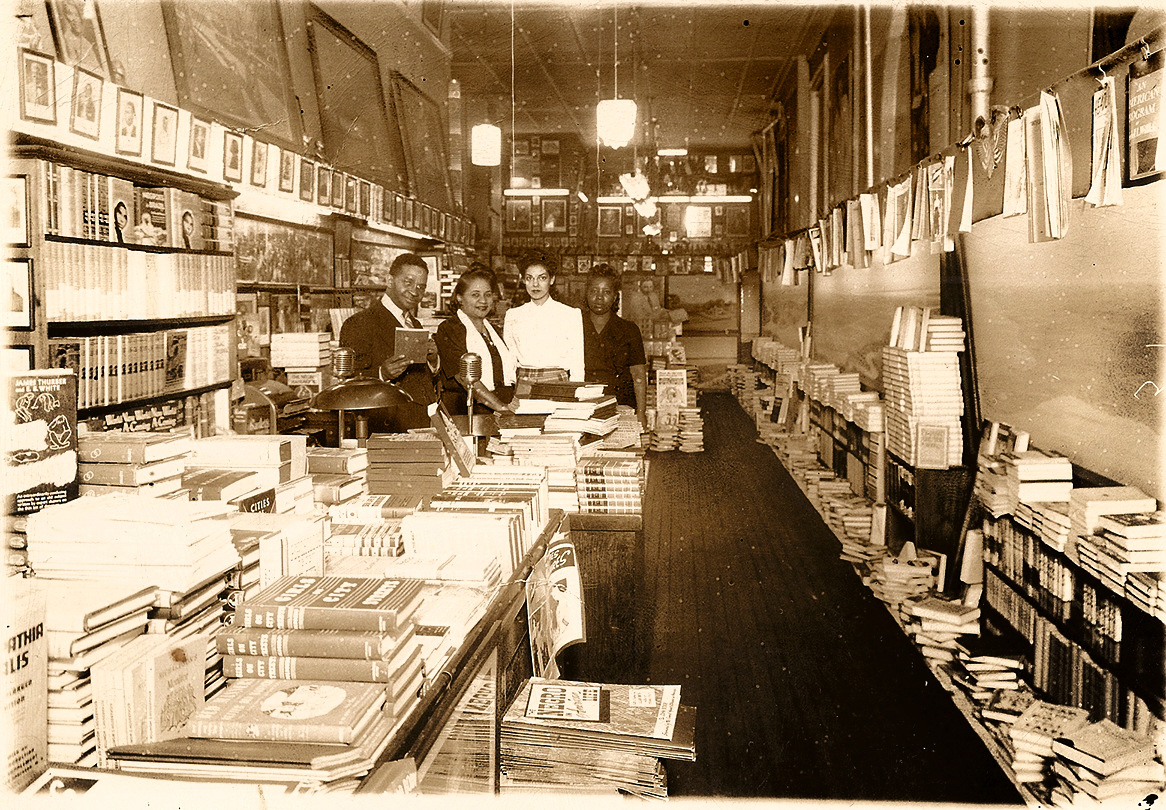

Lewis Michaux with (from left to right) Margaret Banks (Lewis’s sister), Olive M. Batch (Vaunda’s mother), and Miss Duffy inside the original National Memorial African Bookstore location circa 1945. Courtesy of Vaunda Micheaux Nelson.

Lewis Michaux with (from left to right) Margaret Banks (Lewis’s sister), Olive M. Batch (Vaunda’s mother), and Miss Duffy inside the original National Memorial African Bookstore location circa 1945. Courtesy of Vaunda Micheaux Nelson.

One quote of his I keep going back to is this:

I listen to everybody, but I don’t hear everybody. It’s all right to listen, but you don’t hear everybody because if you do, you cease to be yourself and become the fellow you hear. It’s an intelligent thing to do, to entertain the man who’s trying to tell you something, but never lose your individuality.

This is not a new idea—thinking for yourself—but I’d never heard it expressed quite his way.

As essayist Christopher de Vinck observed, “Reading aloud to my children every day gives them the widest entry to that place we call freedom.”

As a former children’s librarian and a believer in the power of books, the power of knowledge, I found this resonates with me. In a broader sense I’d add that literacy, too, is a part of “the widest entry to that place we call freedom.” Frederick Douglass (whom Lewis Michaux admired) understood and lived it. And Lewis surely believed this was the way to freedom for black Americans. “Knowledge is power,” indeed, but only if it leads to independent thinking.

Lewis used books as a compass in his search for self. Books saved him, and he went on to save many others who were fortunate enough to enter the National Memorial African Bookstore.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores by Katie Mitchell. Copyright © 2025 by Katherine Anne Mitchell. Photographs, unless otherwise noted, copyright © 2025 by Julien James. Published by Clarkson Potter, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Vaunda Micheaux Nelson

Vaunda Micheaux Nelson is known for her award winning fiction and nonfiction books for children and young adults. Her No Crystal Stair: A Documentary Novel of the Life and Work of Lewis Michaux, Harlem Bookseller received the Boston-Globe Horn Book Award for Fiction and a Coretta Scott King Author Honor. The Book Itch: Freedom, Truth & Harlem’s Greatest Bookstore won honors from the Coretta Scott King Book Award Round Table and the Jane Addams Peace Association.