How Did America's Banks Get So Much Political Power?

A New Book Traces These Origins to NYC's 1970s Financial Crisis

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: a government spending beyond its means. Puppet politicians doling out impossibly generous contracts to union workers at the behest of big labor. Greedy constituents clamoring for extravagant government spending—free college, municipal hospitals, affordable transportation—which leaders fund through profligate borrowing. Things going belly up when the economy collapses. The larger powers refusing to help so as not to enable a government that, like an addict, couldn’t quit the unfortunate habit of helping poor people. Eventually, all parties bravely coming together to stave off bankruptcy by agreeing to a punishing regime of austerity that sees the bulk of social services sent to the abattoir.

The tragic fate of the liberals who flew too close to the sun and got burned is the boilerplate narrative of financial crisis borne from government spending. Eventually, this saga’s conclusion comes to be seen as an inevitability, the proper outcome. And it is always a self-serving story by those who somehow manage to come out of the ensuing belt-tightening not just unscathed, but richer and more powerful. The impossible simplicity of this tale is what animated historian Kim Phillips-Fein to embark upon Fear City, her brilliant corrective to the story of the 1970s New York financial crisis. Banks, businessmen, and politicians used the crisis to dismantle New York’s social safety net, and have largely succeeded in dictating how it’s been remembered: not as a guillotining, but a fiscally necessary craniotomy.

“Politics remains marked by the notion that when a city must decide between paying its debts or caring for its citizens, it faces not a choice but a foregone conclusion.”

At the time, ascendant conservatives and neoliberal Democrats tacitly agreed on this point, and the political spectrum lurched right as a result. Today, even as left-leaning leaders in America like Bernie Sanders become increasingly viable, they argue for less-than-radical New Deal style services that existed in some form just a few decades ago—and these half-measures alone have been met with hostility by those who finger-wag about financial rectitude. So, if you’ve found yourself wondering why the Democratic mainstream seems incapable of articulating anything other than a means-tested, corporate Frankenstein liberalism, New York in the 1970s and Fear City is a good place to begin.

“The crisis proved a way to change the politics of the city in profound ways without ever talking about race or class explicitly,” writes Phillips-Fein. “The threat of bankruptcy elided policy choices, making it appear as though there were simply no alternatives—as though the transformations were brought about not by anyone’s decision, but by the abstractions of fiscal rectitude and financial necessity.”

Even today, politics remains marked by the notion that when a city must decide between paying its debts or caring for its citizens, it faces not a choice but a foregone conclusion.

“This City is Fucked”

The array of services provided by New York City in the lead up to the 70s crisis was immense but inadequate, shared but segregated. New Yorkers criticized what was broken, but also battled to fix it. And the city had much to build upon: tuition-free education through the City University of New York, a system of local clinics and 24 city-run hospitals, and a 10 cent subway ride in 1950 (equal to just about a dollar today). “The city almost seemed to proclaim a right to happiness and pleasure, even for people insignificant in terms of wealth and power,” writes Phillips-Fein.

This didn’t come cheap. As a municipality, New York’s ability to raise funds for its programs through new revenue, which had to be approved by a tax-wary legislature in Albany, was severely constrained. So local authorities looked up: By the end of 1960s, under Mayor Lindsay, nearly 40 percent of the city’s budget came from state and federal funds. But as Lyndon B. Johnson’s liberal consensus fell apart and the economy faltered, these income streams were drying up. The city’s white tax base began their flight to the suburbs, encouraged by federal politics around homeownership. And New York mayors chose not to confront this reality, resorting to borrowing and hoping the political and fiscal situation would improve.

Phillips-Fein details how an array of financial acronyms allowed the city to keep spending: TANs, RANs and BANs (tax, revenue, and bond anticipation notes). These short term municipal bonds, paid back over a year or so—rather than decades—were happily purchased by banks, which then sold them across the entire country on the back of New York’s rock solid credit rating. Rather than let the city raise taxes, the state loosened the laws constraining New York’s borrowing, and the spigot kept flowing. When Lindsay entered office in 1966, the total volume of these notes was $433 million. By the time he left office, they comprised $2.1 billion out of a budget of almost $10 billion, and the city was $8.5 billion in debt—though shoddy accounting meant no one really knew how bad it was.

In the wake of 2008, readers of Fear City may (not) be shocked to discover that ratings agencies gave the city a green light, with Standard and Poor’s crediting New York’s “amazing resiliency to withstand budget difficulties.” But not everyone was hoodwinked. Phillips-Fein tells the story of Steve Clifford, a 30-something employee in the city’s comptroller office who had long hair, dressed in a dashiki, and seethed at the spending of Lindsay’s replacement, Mayor Abraham Beame. Clifford was one of the first to sound the alarm about how the city’s borrowing and dicey accounting. In November 1974, Clifford penned a memo to a Republican state senator in which he spelled out his concerns with characteristic irreverence: “This city is fucked,” he wrote.

And on March 6th, 1975, after several close calls, Clifford was proved correct. In what was normally a routine ceremony, the comptroller prepared to offer a set of BANs that would be necessary to cover the city’s payroll just over a week away. Representative of the various banks normally purchased the notes, placing their bids in a tin box. But the 11 a.m. deadline for bids passed without a bid. Beame was furious at what he saw as a betrayal by the financial establishment. “The city set the rules; the banks had to follow them,” writes Phillips-Fein.

But Beame was no longer in charge, and the changing financial landscape meant that banks could find profit elsewhere. “Having begun to operate in a global context, they no longer saw their economic and political interests and being inextricably linked to those of the city,” as Phillips-Fein tells it. Eventually, on March 7th, the banks purchased the BANs at their highest interest rate ever after 10 and a half hours of negotiation. “It was clear that the normal relationship between the city and the banks had collapsed,” writes Phillips-Fein. “That’s when the fiscal crisis really began.”

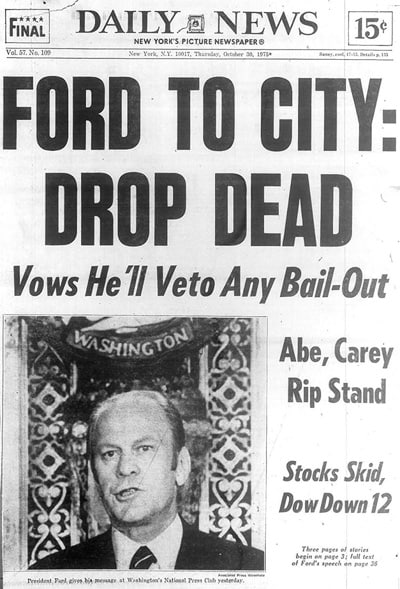

Drop Dead

Fear City doesn’t exonerate New York City, but it does forcefully argue that the state, banks and federal government played their own significant part in the crisis. Everything would have been different had Gerald Ford decided to step in with loans to bailout the city, or if the federal aid, which did eventually arrive, had come sooner. Instead, Ford refused—leading to the famous “Ford to City: Drop Dead” Daily News headline—until its leaders gave up and gave in to a harsh regime of austerity. “24 hrs. Must do what’s right. Bite bullet,” Ford wrote to himself in May 1975, ahead of meeting with Beame and Hugh Carey, New York’s governor.

The crisis happened as the decline of New Deal liberalism intersected with the rise of contemporary conservatism. Rick Perlstein makes a strong case in 2014’s The Invisible Bridge that an insurgent Ronald Reagan made federal intervention by the Ford administration an impossibility (Reagan: “I include in my prayers every day that the federal government will not bail out New York.”) Phillips-Fein doesn’t dismiss this assessment, but her profile of Ford is of a man for whom New York’s spending was almost personally offensive. (While in college, Ford ran his fraternity’s finances and his graduating yearbook notes Ford “put the DKE house back on a paying basis.”)

Some of Ford’s White House ghouls are familiar faces today. Donald Rumsfeld, who served as Ford’s Chief of Staff, appears in the book as one of a cadre of advisors pushing him to let the city implode—declaring “Hell no” at the prospect of a bailout. For those like Rumsfeld who wished to cure New York by gutting hospitals, schools, and saftey, suffering was the treatment, not its side effect. Speaking to Congress in October 1975 as it mulled stepping in, Treasury Secretary William Simon recommended “that the financial terms of assistance be so punitive, the overall experience so painful, that no city, no political subdivision, would ever be tempted to go down the same road again.” To Simon, the crisis was a fundamental indictment of liberalism.

But he didn’t really take stock of his own role in facilitating the crisis. In his previous job, Simon had been in charge of the government and municipal bond desk at Salomon Brothers, quite literally responsible for purchasing New York’s bonds. Even as the roots of the crisis had enriched him personally, he loathed New York’s spending. “What the hell happened to the American free-enterprise spirit: did the puritans need subsidies?” he once quipped.

Big Mac

To get the crisis out of the the Mayor’s hands, banks and businesspeople began assuming something like direct political control over the situation through two semi-governing bodies created by the state and Governor Carey: the Municipal Assistance Corporation (MAC), which would raise money for the city, and the Emergency Financial Control Board (EFCB), which was tasked with getting to a balanced budget by 1978. Staffed primarily by the business elite, both advocated crippling cuts that they themselves would not have to suffer.

The Village Voice ran a piece in September of 1975 on the EFCB titled “Meet Your Junta.” There was no labor representative on the board. No black or Latino representative. There were, however, four public officials, the president of telephone corporation, the president of American Airlines, and the president of Colt Industries. Some on the EFCB and MAC considered themselves liberals but, faced with a supposedly apolitical fiscal reality, they purported to have no choice but steer the city hard towards austerity.

MAC’s most prominent member, banker Felix Rohatyn, believed that “overkill” was necessary to get nervous markets to buy the city’s debt, and the board directed Beame to institute tuition at CUNY even though the $32 million it would raise would do next to nothing to balance the city’s budget (MAC needed to sell $3 billion in notes in 90 days after its creation in June). “Rohatyn told [Beame] that he didn’t get it,” writes Phillips-Fein. “It wasn’t the money that mattered but the symbolism of it, the evidence that the city was changing its ‘life-style’ for good.” The very notion that bankruptcy should be avoided at all costs was the preferred position of the bankers who worried that a judge might put paying firemen or teachers above servicing the interest on municipal bonds.

“Mayor Beame had an axe / Gave the city 40 whacks / When Big Mac saw what he had done / They told him make it 41,” one protest limerick went. From a firehouse in Brooklyn to Hofstra campus of CUNY, activists managed to successfully if sometimes temporarily array of cuts. The results were mainly local since there were no unified city-wide efforts to stave off austerity. The title of the book, Fear City, comes from a pamphlet firefighter and police groups hoped to distribute at the airport to highlight the dangers caused by civil service cuts—eventually stopped by a judge’s injunction.

“Those rich men who prescribed the city’s leaching never suffered from it themselves, and they put forward a supposedly neutral language of inevitability to elevate a deeply political financial ideology—one that wields enormous influence today.”

The structures of the fiscal regime were not susceptible to normal democratic pressures. “The marchers and protestors could not affect the people who had real power: those around the country who had purchased the city’s debts,” writes Phillips-Fein. “These investors were now Beames constituents as much as the residents of New York, and perhaps more so.”

Finally, at the end of November of 1975, Ford agreed to step in with $2.3 billion in short term loans after the state raised taxes. While not the end of the fiscal crisis, this proved the turning point—the bond markets now had a sign the feds would help if things got bad, allowing risky and self-interested financial maneuverings to continue with relative ease.

Those rich men who prescribed the city’s leaching never suffered from it themselves, and they put forward a supposedly neutral language of inevitability to elevate a deeply political financial ideology—one that wields enormous influence today. And Democrats learned all the wrong lessons from the fiscal crisis. Rather than fight the logic of finance, they embraced it, and it has become intractably woven into the fabric of the party. Now the Democratic mainstream relishes in tsk-tsking its leftist flank (and even its constituents) about what policies are realistic. Healthcare is perhaps the most obvious example, with the Affordable Care Act standing as both a major achievement (especially in its expansion of medicaid) but also a confusing, broken, and flawed market-based healthcare system originally proposed by conservatives. And charges from Hillary Clinton and other prominent Democrats that single payer is impossible—this as the Democratic base and some legislators clamor for it—leads them to not even advocate for it.

When Democrat Ed Koch succeeded Beame as mayor of New York in 1977, he ran on a platform of reality-based liberalism. In office, his shuttering, against massive protest, of Harlem’s beloved Sydenham hospital seemed to proclaim a militant rejection of all that it had symbolized. Now, a commitment to a robust and functioning social state by local politicians in one of the most progressive cities in the country seems lost. While Bill de Blasio swept to power in 2013 on an ethos of progressivism, he appears uncomfortably dependent on real estate developers to help build a more affordable city.

For his faults, however, de Blasio is a veritable Eugene V. Debs next to to Governor Andrew Cuomo—perhaps the epitome of a post-crisis New York Democrat—whose solution to a collapsing rail system is to call for the privatization of Penn Station and an investment in self-driving cars. His free college tuition plan, announced earlier this year, is tailored to help the middle class, and resembles not a genuine commitment to education, but a transaction between the state and citizens in which the later must meet certain onerous conditions to enjoy the largess of the former.

And above the political fray, the financial control board created during the crisis remains; diminished but not dormant, still looking over the city’s budgets from its office near Wall Street. Should New York default on its debts or run a budget with a deficit above $100 million, the board would awaken from its slumber, its blades whirring into action, ready to make the will of the powerful felt once again.

While a cautionary tale on the substantial limits of socialism on the municipal level (cities are not nations—they can’t borrow endlessly), Fear City is also a reminder that a far bolder world is possible. Had a democrat been in the White House in 1965, had banks not turned a blind eye in favor of profit, had the statehouse been more friendly—who knows what New York might look like today. Thinking about what was lost during those years in New York is staggering and tragic: free tuition at CUNY, hundreds of firehouses, childcare centers, much of the city’s robust municipal hospital network.

Many of these systems were hampered by racism and underfunding in their heyday—this is why, in crucial ways, treating the New Deal liberalism as a panacea is, itself, deeply limited. But regardless, the staggering cuts in the 1970s hurt those already worst off—people of color and the poor—eliminating, rather than fixing, the public sector.

Fear City details how austerity politics tightened the grip of the invisible hand on the throats of the weakest in society in the 1970s. But Phillips-Fein reminds us this outcome was not inevitable at the time. And it need not be today.

Isaac Kaplan

Isaac Kaplan is a writer living in New York and an editor at Artsy.