“This year has been rock bottom for me,” Candice wrote after the overdose. She would soon turn twenty-six. “25 years old and what’s to become of me?” Three times, she copied the question into the spiral notebook she was using as a journal, like a naughty schoolgirl assigned to chalk sentences on the blackboard.

It was partly a question of money. Life had gotten expensive, even as inflation eased from its double-digit highs. In November 1976, right after Jimmy Carter’s election to the presidency, Candice moved to a larger place on the corner of Castro and Nineteenth, at the staggering cost of $225 a month. She must have been counting on her porn earnings. But two weeks later, she lost her ATD benefits, though she was arguably more disabled than ever before. “How can a drug dependent young woman re-enter the world of reality?” she wondered. She had weaned herself from heroin several times since the summer, the first time in a clinical setting, likely with methadone, and the second time using her own cocktail of cures, from Quaaludes to whiskey. The ministrations of a devoted new man named Mark helped her through the worst of it. But then came “a month-long coke binge.” And on it went.

Candice had stumbled into a “very quick, easy, and successful dope business,” but selling drugs only partly offset the cost of her habit. She continued her film work, booked some singing gigs that holiday season, and took “a crummy office temp job.” She ended the year in debt to her friend Karen, to her dope connection, to the photographer who had taken some headshots to advance her performance career. On occasion, she went hungry.

She soon discovered she was pregnant again, this time by Mark. The prospect of a third abortion—the second within a year—mortified her. As she waited to pick up the emergency Medi-Cal voucher that would pay for the procedure, she castigated herself for having failed to expend even the “little effort” a diaphragm required. She seemed touched, even amazed, that her boyfriend stayed with her at the clinic, telling Danny about the way Mark held her hand while they scraped out her uterus.

Even as porno chic faded, its afterglow lingered in the industry.She cleaned up again after that, for five days, the “longest span in ages.” But then she relapsed, shooting morphine, shooting Demerol. She placed herself among “the league of… ‘hard users’ or ‘hypos’ as we’re sometimes referred to.” She found a steady new client, “a Saudi Arabian princess who’s a skin & bones junky dyke,” who lived in a lavish apartment on Telegraph Hill. Princess Jay was one of the youngest daughters of King Saud; Candice met her through friends who supplied the royal entourage with drugs. The dealer was ripping Jay off, Karen remembers, and so Candice became the princess’s supplier, at what she deemed a fairer price.

*

Even as porno chic faded, its afterglow lingered in the industry. Deep Throat had created what Forbes called a “porno star system.” A handful of actresses—Linda Lovelace and Marilyn Chambers and The Devil in Miss Jones’s Georgina Spelvin—had made a handful of producers and distributors very rich. As one adult-film veteran noted, “There is nothing as valuable as a girl who is innocent and beautiful—and who knows how to handle herself. It’s worth the same in this world as a man who’s been to graduate school for seven years.” Innocent and beautiful coded white as well as young; there were vanishingly few Black female performers. Innocence was tantalizingly vulnerable; it faded fast.

One media studies scholar warned in 1977 that pornographic actresses tipped into “coarseness” almost overnight, “as if a Dorian Gray syndrome were operative.” The industry’s appetite for fresh, pale faces and bodies was insatiable. Nonetheless, the supply of women who thought they were liberated enough, or knew they were hungry enough, to pit themselves against the “final refuge of narcissism” more than met demand.

As Candice battled debt and drug dependency, Candida Royalle’s renown as a pornographic performer grew. In October 1976, she and her formerly homeless friend Laurie Detgen, aka Lailani, who was still barely of age, auditioned together for Hard Soap, which Candice called “a high budget X-rated take off on Mary Hartman,” Norman Lear’s popular television sitcom, itself a spoof of soap operas. They snagged the two leading female roles. They’d each make a thousand dollars for four days of work—more than ten times what the office job paid, a month’s rent in a day. This was the big-time. Candice decided she and Lailani were now officially “porn queen beauties,” like their “porno queen friend” Annette Haven, who had starred in several films, including the bicentennial-themed Spirit of Seventy-Sex, in which she played Martha Washington, giving blowjobs in a mob cap.

The porn star was a recent arrival in the firmament of American celebrity. Neither “porn star” nor “porn queen” had appeared in books, newspapers, women’s magazines, or entertainment industry periodicals until late 1972. But just four years later, she was a familiar figure, her louche stardom burnished by television and personal appearances and sustained by the proliferating sex press. Big-name porn queens commanded somewhat higher fees than workaday actors, but their status remained precarious and their incomes insecure. Those who could branched out. Linda Boreman had reclaimed her birth name but called the company she helmed Lovelace Enterprises; it sold T-shirts and shampoo. Marilyn Chambers hit the nightclub circuit as a singer. Andrea True, a relatively minor performer in some fifty sexploitation and hardcore films during the ’60s and early ’70s, was recast as a “porn queen star” when she released a disco single, the suggestively titled “More, More, More.”

The porn-star phenomenon resulted, in part, from a deliberate campaign for legitimacy by the group of directors, producers, publishers, and lawyers who, in the late ’60s, had constituted themselves as an adult industry, with its own trade association, the Adult Film Association of America (AFAA). The AFAA, like Al Goldstein’s Screw magazine, took shape in the immediate wake of Nixon’s election to the presidency. Both policing and promoting the respectability of pornography, its leaders mounted an aggressive defense against the counterrevolution that threatened to supplant the sexual liberalism of the counterculture. Modeled on the Motion Picture Association of America, the AFAA refused to lurk in the shadows, instead defending sexually explicit fare as part of a “new freedom born from enlightenment.” “We’re in a business we should not be ashamed of,” one industry spokesman told the Independent Film Journal in late 1969.

The AFAA’s spotlight strategy meant that, by the time Candice was shooting hardcore regularly, ambitious 35mm pornographic films often launched with formal, openly advertised premiers. The year she filmed Hard Soap, Candice attended a midnight preview of one of her earlier films, probably Honey Pie, at the Presidio Theater, which also hosted a well-publicized annual Erotic Film Festival. She and Danny had gone to the premier of his film, Cry for Cindy, as well as a launch party for another of hers, likely Baby Rosemary, one of her two 1976 releases to earn a review in Variety.

The reviews were generally lousy, and they didn’t yet mention Candida Royalle or any of her other aliases, but the skin magazines came calling all the same. The growing number of explicit glossies—slicks in industry parlance—on offer at newsstands, and the increased space mainstream newspapers and trade magazines devoted to the adult film industry, meant more column inches to fill and more publishers seeking stories. Shortly before Candice’s audition for Hard Soap, a reporter from Hustler contacted her. Being interviewed had made her “feel so special,” she wrote, even as she worried that she wouldn’t be able to show the article to her parents.

Candice also considered writing and launching her story into a dawning age of memoir. In the ’70s, the diary craze of Candice’s girlhood yielded to new and less-private genres of feminine self-scouring and self-exposure, as if the therapist’s couch had burst its stuffing all over the public sphere. Television talk shows, a genre that began with Phil Donahue in 1967, proliferated and grew increasingly intimate. In 1973, An American Family, a documentary series on PBS that prefigured the era of reality TV, riveted the nation with the miniature dramas of the Loud family, including one son’s coming out.

In 1974, American Family’s matriarch, Pat Loud, published a confessional detailing her experience with the television show, one among a spate of memoirs centered on the family traumas of relatively minor celebrities. Serious, sexually explicit feminist novels like Alix Kates Shulman’s Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen (1972) and Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying (1973) turned the standard male bildungsroman formula inside out, offering up the grist of consciousness-raising to a broad and passionate readership. Celebrity former sex workers published autobiographical tell-alls. Xaviera Hollander made headlines with The Happy Hooker in 1972; three years later Fanne Foxe, the Argentine stripper and mistress of disgraced Democratic congressman Wilbur Mills, used Hollander’s ghostwriter when she published her own life story.

In 1974, when Candice read Sylvia Plath’s autobiographical novel The Bell Jar (1963), she had felt inspired “to immortalize” her “thoughts and adventures more closely” than she had done in recent diaries. At that point, she didn’t think anyone else would ever read her words, because her life wasn’t “quite entertaining enough.” But by 1976, her life had changed. After devouring a titillating novel called Inside Daisy Clover, written in the form of a teenager’s explicit diary, she thought again about the potential audience for her journals. “How many women can say they did an x-rated film up on a ranch in Northern California,” Candice wrote of a film in which she “got it on with a real life ‘professional’ cowboy…. The scene was supposed to be of me & another guy fucking on a horse, but we simulated it.” The ambiance, she said, had been “just like in the Misfits with Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable.” She figured a book based on her diaries, and featuring encounters like that one, would be “a best seller for sure.” That was vainglory. But Candice was right that the audience for her new style of stardom was growing. In October 1976, COYOTE asked Candida Royalle to be photographed, as a VIP, while entering the third annual Hookers’ Ball, which crammed two thousand revelers into the San Francisco Hilton and made the front page of the Examiner.

*

John C. Holmes was one of the biggest names in the porn business, renowned for the astonishing size of his penis, reputed to be over a foot long. When Variety called Holmes “a performer of lengthy credentials,” it referred only partly to his filmography, which encompassed nearly three thousand appearances before Bob Chinn’s Hard Soap, which would be Candice’s breakout movie. Erectile dysfunction provides Hard Soap’s running joke—inverting the more common Deep Throat or Analyst formula, in which the female protagonist must be cured of frigidity. But like those and many other golden-age porn films, Hard Soap has a therapeutic substrate. “Dr. Holmes” is a psychiatrist, the physician who cannot heal himself. Linda Lou (Candida Royalle) and Dr. Holmes’s wife, Penny (Lailani) conspire to effect a cure. The unveiling of Holmes’s erect penis is the climax of the movie.

Hard Soap has softer edges than the films Candice had made before it. Most of the action takes place in Penny’s suburban home, where the two friends dish at the kitchen table, and sometimes on top of it. There’s a lot of natural light, and the actors generally look healthy. (Chinn trained at UCLA film school.) The score—which parrots the trembling organ melodies of midcentury soap operas (organ, get it?) and the iconic saxophone riffs of Blake Edwards’s Pink Panther films—adds a note of camp. The opening credits feature the Liberty Bell, perhaps a wink to the bicentennial year in which Hard Soap was made.

The hours were long. Constraints of space and budget, as well as the schedules of crew members who held down straight day jobs, meant that adult features were often made by night or on weekends. (Union members—sound men, camera operators—liked to moonlight on porn shoots because they were quick and typically local.) Many skin flicks were shot in as little as three marathon sessions, and few directors could afford more than five. The work was physically arduous, especially for the female performers, who maintained awkward, even gymnastic poses, sometimes for hours, all the while striving to look as if they enjoyed it. Scripts that featured sexual violence were especially grueling. One actress told Stephen Ziplow, the author of a how-to guide for would-be porn directors, that she had found it “easier to be raped for real.” By comparison to her violent scene in Easy Alice, Hard Soap was short on pain and long on play.

At that point, porn typically paid performers by the day rather than by the sex act, though the deal memo with an actress generally contained a checklist of what she would and wouldn’t undertake. In Hard Soap, “Candice Chambers” fellates four men—one while wearing a ski mask—and has vaginal intercourse with two. Each sex scene would have had to be filmed three times: first “MOS” or motor-only, without sound; then again with sound, but short of completion; and finally to capture the male orgasm, the temperamental proof-of-concept image known as the “money shot.” (Ziplow recommended filming at least ten male climaxes, “to allow for some freedom of choice” in the editing room. He also suggested that directors “bring along a can of concentrated milk,” or egg whites, milk and sugar, to confect a counterfeit ejaculate in a pinch.) Almost every sex scene also involved extreme close-ups of performers’ genitals, known as “meat” or “medical shots.” These images were like verbs, indispensable to the grammar of pornography. “The meat shot is the only real difference, outside of fellatio or cunnilingus, between the pornos and the simulated sex films,” one adult director argued. To get those “anatomical” images in focus and properly lit, a gaffer or two was essential. On the set for a movie like Hard Soap, four or more crewmen swirled around the couple having sex in bed.

None of those ways of justifying her choices had quite blunted the force of the work itself.At points in Hard Soap, Candice looks like she’s having fun. She does not partner with the punishingly enormous Holmes onscreen, though she later recalled that one day during rehearsal, he led her into a back room and had intercourse with her, more or less consensually. Holmes liked “throwing his weight around,” she said. Candice was booked to film a couple of loops for Jerry Abrams the week after Hard Soap wrapped, and she hoped those shoots would be brief, since she was “sure to be exhausted by then.” And no wonder.

Though she generally disliked seeing herself onscreen and complained that Chinn had caught all her “worst angles,” Candice watched Hard Soap at least three times in theaters and kept a personal copy. (She hung on to only five of the fifteen feature-length films she made between 1975 and 1977.) As her one-time co-star Howie Gordon points out, pornography is a genre of compromises. “In a porn film, if you are not too humiliated by what transpires between the sex scenes, then you may have yourself a rollicking success on your hands.” The adult industry rewarded even modest professionalism, he says. “If you showed up on time and were sober and had your lines memorized, they treated you like you were Laurence Fucking Olivier.”

“I love professionalism,” Candice had written after the Psoriasis debacle. And as in many of her films, she outshines the context and much of the cast of Hard Soap, with a big screen presence and a lot of style, courtesy of her own ’50s fashions. She knows her lines, and she reads them with conviction. She had also learned, by then, the tricks of the hardcore trade: kiss with your tongue, not your lips, or your partner will wind up smeared with lipstick. Don’t block his genitals with your face. Be ready for long pauses, which inevitably require the male player to recover his arousal. And especially, as she later wrote, “Never, never look into the camera. It breaks the fantasy for the viewer.”

A dedicated student of camp through her close observation of the Cockettes and her work with the Angels of Light and its offshoots, Candice brings a comic snap to Linda Lou’s serial seductions of stock characters: the mooning milkman, the peeping paperboy. As Penny, Lailani, barely twenty, looks smacked-out and ethereal, her wide, pale, glassy eyes framed by pencil-thin eyebrows, Jean Harlow to Candice’s Rosalind Russell. For much of the movie, the viewer is teased with the possibility that Linda Lou and Penny may eliminate the limp middleman and head off to bed together. Their offscreen friendship is palpable. Candice and Lailani hold each other up, even though they never wind up lying down together.

*

During some sober moment in late 1976 or early 1977, Candice sat down with a ballpoint pen and a yellow legal pad to reckon with her “new career as a porn queen.” Her musings turned into a six-page essay, which she titled “Close Call with Male Power Game.” In it, she recalled moving west, after “serving my time in the women’s movement.” At first, it had seemed like San Francisco would fulfill her feminism. She had managed to build her life “almost entirely with unoppressive men,” which led her to “forget about the remaining 3/4 of the population of chauvinist pigs, a term I haven’t used in many years.”

But porn had brought her old feminist fury to the surface again. She had rationalized the work, which she took because she was “seriously broke”; hardcore was, as she said, “financially rewarding.” She had “validated” her explicit roles by treating them “as an exercise in acting,” whose mastery would further her “ultimate goals,” the “stage & silver screen.” She told herself that she was slaying the double standard.

And yet, none of those ways of justifying her choices had quite blunted the force of the work itself. “The world of pornography, from the simulated quickies to the higher budget feature films, is not at all concerned with what people have learned from women’s or men’s liberation, and in fact still bases its success on all the old traditional oppressive male attitudes toward sex,” Candice wrote. She had tried to ignore the genre’s “obvious insult to my intelligence” and “consciousness” by dwelling on the power of the performer over the “poor horny saps” that made up the bulk of hardcore’s audience, men whom she never met and could scarcely imagine. She told herself they were “being fooled,” cheated—that the porn queen had the last laugh. That mantra had helped her “overlook my own self-prostitution for something I absolutely did not believe in.”

But she didn’t, couldn’t buy that script for very long. And so, for the second time, she decided she was done. “So much for the world of pornography,” she wrote. “It was a brief flirtation with a male dominated industry.”

Had she held to this line, Candida Royalle might have traded her emerging status as a porn queen beauty for a role in the feminist anti-pornography organizations then taking shape in California.

__________________________________

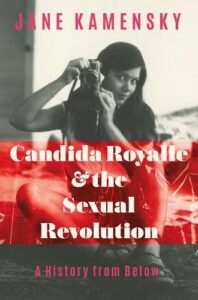

From Candida Royalle and the Sexual Revolution: A History from Below by Jane Kamensky. Copyright © 2024. Available from W.W. Norton & Company. Featured image: Victor Alcorn