Merriam-Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary describes a jazzman as “a performer of jazz,” with the term dating back to the Jazz Age in 1926. But while it provides definitions for fancy woman, saleswoman, and madwoman, it doesn’t recognize the word jazzwoman (or jazz woman).

The same holds true for sideman, which we learn means a member of a band, especially one playing jazz or swing, and more specifically “a supporting instrumentalist.” But nada for sidewoman or side woman (although it does define a widow woman and a little woman).

What a dictionary includes and what it ignores offer insights into not just a nation’s language but also its biases. Now, as then, America’s most trusted glossary sees jazz as a man’s universe. Which shouldn’t surprise anyone since it recognizes a first baseman, but not the women who field that position. And while it knows about train porters, it has nothing to say about the porterettes or maids who, in the days of the Pullmans, set rich women’s hair, boxed their hats, tucked in their berths, and performed other up-close tasks that could have gotten porters lynched.

The three maestros helped push Mary Lou, Lil, and other women to the top even as…they held them back precisely because they were women.Merriam-Webster doesn’t just reflect norms, it legitimizes them. There weren’t many porterettes or maids on sleeping cars, but there were some, just as there were women owners and players in the Negro Leagues. As for jazz bands, few knew or know about the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, sixteen blazingly-gifted music makers who in the 1940s raised the roofs at the Regal in Chicago, the Howard in Washington, and, repeatedly, at New York’s legendary Apollo Theater. There’s even less record of the all-girl, all-Black territory and college bands of the Swing Era.

The early jazz women we do read about—from Billie Holiday to Ella Fitzgerald and Ivie Anderson—were singers, generally for big bands like Basie’s, Ellington’s, and Armstrong’s. It is no accident that they were gorgeous as well as talented. Duke, Satchmo, and the Count thought they knew what audiences wanted, and so made sex appeal a priority. They also knew that, in addition to the racial slurs that came with being Black, jazz women were belittled as warblers, thrushes, and canaries.

One of the few to break through those barriers was Lillian Hardin Armstrong. She demonstrated as early as the 1920s that jazz women could do more than sing, in her case by playing the piano, composing, arranging, and leading the band. Even so, if history recognizes her at all it is as Satchmo’s second wife, musical enabler, and all-round helpmate. Books on him depict her as puffed-up and jealous, because she had more refined manners than he did, and she rightfully resented not getting the credit she warranted. As for embroidering her academic and other records, she did, but there’s reason to believe the embellishing was partly Louis’ doing, to make himself seem smart by having picked a valedictorian as his bride.

Lil, who grew up in Memphis, played marches on the piano in grade school, hymns in church, and, after she and her mother moved to Chicago, she demonstrated sheet music at a store on State Street. Her style was what she called heavy, like Willie the Lion Smith, and she was crackerjack enough to be invited into King Oliver’s band a year before Louis arrived in the city and on the scene.

While she was only mildly impressed by him, he was so taken with her that Hot Miss Lil became part of his original Hot Five. She co-wrote hits with Satchmo, encouraged him to join and then leave Fletcher Henderson’s band in New York, and helped launch his career and live up to her claim that he was the World’s Greatest Trumpet Player. Later, she toured as “Mrs. Louis Armstrong and her Chicago Creolians,” an all-girl band of fourteen, was house pianist at Decca Records, and performed as a soloist.

How good was this jazz pioneer? Her biographer in 2001 called her “the most important woman in jazz history,” which was overreaching, but she was one of the most important of her time. A Chicago Defender writer came closer to the mark when, in 1934, he wrote, “to the surprise of this chronicler and the other patrons as well, likely Mrs. Louis Armstrong’s all-girl orchestra does not suffer in comparison with that of her more famous hubby…Lil herself is a great pianist and arranger.” The reviewer, a man of course, didn’t hide his skepticism that a gals’ band could be anything but a “novelty,” or could ever measure up to the likes of Armstrong and Ellington. But after hearing Lil a second time he found himself “a fine supporter of girl bands and musicians. They offer plenty [of] jazz and swing and will entertain you with the late[est] song hits, as capably as any of the masculine orchestras.”

Mary Lou Williams ran into similar skepticism while doing even more than Lil to make jazzwoman a Webster-worthy concept. Known in Pittsburgh as the Little Piano Girl, as a three-year-old she played spirituals and ragtime on a pump organ while propped on her mother’s lap. At six, she got racist neighbors to stop throwing bricks into her family’s house by giving them private concerts and brought home money that helped support seven siblings. By fifteen she was a full-time musician.

Fats Waller was so delighted when he heard the teenaged Williams that he playfully tossed her into the air. Celebrated pianist Art Tatum took her on tours of jazz clubs. Later, her piano-playing, composing, and arranging catapulted her to the vanguard of Kansas City swing, be-bop, and, after she became a devoted Catholic, sacred music, including writing a jazz mass that thousands heard at St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Whatever the genre, she was a pioneer and innovator. When she died in 1981, the New York Times called her “the first woman to be ranked with the greatest of jazz musicians.”

Williams’ career intersected with those of Armstrong, Ellington, and Basie. In 1953, Louis offered her a job in his All-Star band; she declined, knowing that would mean sharing the spotlight. She joined the Count in mentoring young musicians in Kansas City and wrote music for his orchestra. While she already knew him and his gifts, when she heard the Basie band in Paris in 1954 “I couldn’t sit down during the concert, I couldn’t stop dancing.”

She was closest to Duke, although she vacillated between adoring and abhorring him. She first ran into his band in the mid-1920s, when it was still called the Washingtonians. She wrote fifty or so compositions and arrangements for him from the 1940s through the ‘60s, and found his freewheeling rehearsals heavenly. But she resented that when she needed money, Duke wouldn’t hire her even though she’d bailed him out in the early ‘40s when ASCAP wouldn’t let him broadcast his own compositions. As for Ellington personally, “I never had too much to say to Duke,” Williams wrote. “I always liked being around sidemen or little people.” Ouch. That didn’t stop Duke, in his memoir, from calling her “perpetually contemporary” and saying, “she is like soul on soul.”

Like Lil, Mary Lou had to contend with a double stigma. They were Black in the era of Jim Crow persecution, and female at a time of rampant sexism. Ellington, Armstrong, and Basie weren’t exempt from such misogyny. While they employed more women than their fellow bandleaders did, they shared the prejudice that it was unladylike to play a trumpet, trombone, or any instrument other than perhaps the piano. The three maestros helped push Mary Lou, Lil, and other women to the top even as—in ways they may not have realized—they held them back precisely because they were women in Black and jazz worlds controlled by men.

While African-American jazzmen had a hard time on the road, be it finding accommodations or earning a living wage, African-American jazzwomen had it tougher, with even lower wages, fewer options on restrooms or rooming houses, reluctance on the part of the State Department to send them on tours, and a tacit assumption that this ostensibly egalitarian music form was a male bastion.

Melba Doretta Liston made a name for herself a bit later, and without the pizzazz of Lil or Mary Lou. Liston stood out because her instrument wasn’t a refined keyboard, but a hard-blowing trombone. She toured with the Basie band in 1948, one of just three female instrumental players to perform with him. The rigors of the road burned Liston out, however, and in later life she was best known for arrangements she wrote with pianist Randy Weston.

If Mary Lou Williams, Lil Hardin Armstrong, and Melba Liston were the exceptions to the rule that women should sing and not play, diva Bessie Smith was its embodiment. Young Bessie perfected her singing on Tennessee street corners, where she and six siblings earned enough to keep going after their parents died. A generation later she was crowned Empress of the Blues as the most successful Black vocalist of the 1920s and ‘30s. Smith helped open the singing profession to African-American women, drawing on slapstick and theatrics to get her audiences to listen to her lived stories of surviving poverty and racism, sexism and the trials of love.

Of her nearly two hundred recordings, several of her best were crooned in 1925 alongside Satchmo, including “Cold in Hand Blues” and “Sobbin’ Hearted Blues.” She already was a star by then, while he still was Joe Oliver’s masterly sideman. “Everything I did with her, I like,” Louis said. “She had a quick temper, made a lot of money. A cat came up to her one day, wanted change for a thousand-dollar bill—trying to see if she had it. Bessie said, yeah. She just raised up the front of her dress and there was a carpenter’s apron and she just pulled that change out of it. That was her bank.”

While African-American jazzmen had a hard time on the road, be it finding accommodations or earning a living wage, African-American jazzwomen had it tougher.Billie Holiday also knew about the blues she sang—spending time in a Catholic reform school, fighting off a rapist, scrubbing white people’s stoops, and running errands at a brothel in exchange for being able to sing along with recordings by Satchmo and the Empress. Like Bessie, Billie showed that women belonged on center stage rather than in supporting roles. And like Smith, Holiday’s unorthodox but affecting singing brilliantly incorporated social critique, most poignantly in “Strange Fruit,” the poem-turned-song that became an anthem of the civil rights movement. At the mixed-race Café Society nightclub in Greenwich Village, she always sang it as her closing number. The waiters stopped all service in advance, and the room went dark save for the spotlight on Holiday’s face as she prayerfully chanted:

Southern trees bear strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees

Pastoral scene of the gallant south

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

While Billie gave Louis much of the credit for her elegantly cool phrasing and feeling, Count Basie actually did more to launch her to stardom. Basie was awestruck as soon as John Hammond introduced them in 1937 and she was soon working for him. “I joined Count Basie’s band to make a little money and see the world. For almost two years I didn’t see anything but the inside of a Blue Goose bus, and I never got to send home a quarter,” she wrote in Lady Sings the Blues.

There were a lot of great things about the Basie band, and the experts are just beginning to pick it to pieces after almost twenty years to find out what made it so great… I still say the greatest thing about the Basie band of those days was that they never used a piece of music, still all sixteen of them could end up sounding like a great big wonderful one sound… For the two years I was with the band we had a book of a hundred songs, and every one of us carried every last damn note of them in our heads.

Basie and Billie split in early 1938 for reasons that, like most such partings, depended on who was telling the story and when. “I quit,” Billie said. Her biographer said she “was fired—‘asked to leave.’” The press and others blamed Hammond. Basie booker Willard Alexander claimed responsibility, saying he let her go because “Billie sang fine when she felt like it. We just couldn’t count on her for consistent performance.” For his part Basie, who generally called Billie by the endearingly formal form William (she called him Daddy Basie), said, “I loved Billie an awful lot. I loved Billie as far as love could go.”

As for her leaving, the Count wrote, “according to the story, I had let her go because I felt that it would be easier to work without a girl singer. But I think Billie left because she got a chance to make more money than we could afford to pay at that time. As for me not wanting a girl singer, how could that be true when we replaced Billie with Helen Humes as fast as we could?”

Billie and Louis shared a manager, Joe Glaser, who made a request of her he never made of the rotund Satchmo: skinny down. “He told me he hadn’t booked me anywhere because I was too fat. I told him to tell that to Mildred Bailey the Rocking Chair Lady. I was big, sure, but she still had plenty of pounds on me. But I started losing weight and finally he told me he had a job for me at the Grand Terrace Club in Chicago.”

Weight was a lifelong issue for Velma Middleton, a former chorus girl and dancer who sang for Armstrong bands for twenty years. Critics mocked her size (she weighed nearly three hundred pounds), her vocal style (less than pitch perfect), and her on-stage antics (miraculous splits and comic duets). What mattered was that audiences adored her, and Louis did, too. Sadly, she suffered a stroke during a tour of Africa and in February 1961, in just her mid-forties, she died alone at a hospital in Freetown.

These sidewomen’s experiences with the three bandleaders make clear that being pretty mattered almost as much as being racy (Velma, to some eyes, was the exception). “They used to call me The Pretty Department,” said Maria Cole, whose stage name was Marie Ellington and who was no relation to Duke though she sang for his band as well as Basie’s. “We got up to do our numbers and you sat there, regardless of whether you were performing or not. To look pretty,” she said of her time with Duke. Ellington later acknowledged that Marie, who married singer Nat King Cole, “was so pretty it took a while for audiences to realize that she was presented for the purpose of singing rather than just to be looked at.”

Kay Davis worked with Duke from 1944 to 1950, but at first he’d stand her on stage merely to hum and be eyeballed. “I used to call home at least once a week crying,” she said, “because I wasn’t doing anything significant.” (Duke said it was significant, that “she had perfect pitch…so we decided to use her voice as an instrument.”) Another reason for Kay’s crying: the “baby doll pumps” singers had to wear, which “hurt our feet so we could hardly cripple out on stage.”

But she says Duke “was always very kind to me… He had a respect for me I wasn’t due—about my talent… It was, I think, kind of amazing to him that I had finished college, you know, gotten a Masters in Music and [yet] I would go with the band…But this was just a dream come true. It was very exciting.”

Davis and her sister sidewomen also were taught that the way to get along with the sidemen was to be one of the boys. That meant shooting craps and playing cards on buses and trains, the way Billie Holiday did. It meant accepting the upper berths when the boys claimed the lower ones, because they had more seniority and bravado. It meant sometimes tolerating more teasing than they’d have liked, and taking care that kidding didn’t descend into harassment. But most of the time, as Lu Elliott said, boys in the band “looked out for me.”

Elliott’s real name was Lucy, but she changed it to Lu at Duke’s suggestion. “He said, ‘I think it sounds much better to go out and say, “bringin’ to you our vocalist, Lu Elliott’ than saying ‘Lucy Elliott.’” Pianist Judy Carmichael got different advice when she went backstage to say hello to the Count and, with a quick look and the merest of words, he made clear she should stop wearing the tight jeans that she called “spray-on pants.” “I was horrified. I was the girl who wanted to be taken seriously, not to look like a twenty-something groupie trying to hit on one of the band members,” she wrote. “I’ll never know if Basie meant to give me a particular message, but I heard what he was saying and changed what I wore from then on when I went to hear music.”

Gender wasn’t the only challenge facing Black jazzwomen. They lived with racism that sometimes was even more insidious than what Black jazzmen faced. Jewel Brown, who replaced Velma Middleton in the Ellington band, says her mother steeled her for that, teaching her “how to act among the Caucasian people. She said, ‘You never want to look at a Caucasian man sitting with his wife. Look above the head, like you, like you looking but you not looking at them. And if anything, look at her, not him.’”

Mary Lou Williams, who was old enough to be Jewel’s mother, saw that bigotry for herself when, as a teenager in the late 1920s, she worked as a piano player at a roadhouse-brothel outside Memphis: “The clientele consisted of barrel-bellied, loud-mouthed, third-grade readers whose preoccupation was gambling and girls. A rich, big fat redheaded, freckle-faced plantation owner came up to Memphis from Mississippi with this little nurse. Every night he’d give me $5 each time I played his requests. Around the third night his girlfriend tried to take him away, saying, ‘You like nigger girls?’” The female owner of the club sent Williams home, fearing for her safety. “When I returned to the job, she told me that this sick man had paid the cook $50 to kidnap me and bring me to his farm in Mississippi.”

“I had heard many tales about black women being kidnapped and taken to Mississippi across state lines, out of the reach of Tennessee authorities. And when their parents had gone to get them, they were shot at the gate.”

Was it all worth it for these talented women? Lu Elliott believed it was, saying, “I have benefited by just being able to wear the banner of having been a Duke Ellington vocalist…It can only enhance anything that I’ve ever done or will do in this business.” Not so for the Queen of Swing Norma Miller: “It was just a living. I did one-nighters with Basie, and I’ve asked God, if you ever get me out of this, please never let me do this again.”

__________________________________

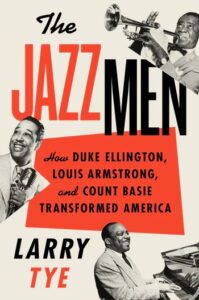

From The Jazzmen: How Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, and Count Basie Transformed America by Larry Tye. Copyright © 2024. Available from Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.