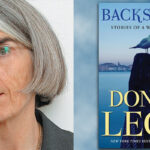

Harper Lee’s ‘Go Set a Watchman’ in 10 Quotations

Tell Don't Show: Atticus/Scout Fan-Fic, From the Source

Every other week Oscar van Gelderen, the publisher at Lebowski in Holland, who blogs here, summarizes a notable work of fiction in ten quotes, with an emphasis on style and voice. No spoilers. This week, the ultimate sequel-cum-prequel, Harper Lee’s much-discussed Go Set a Watchman.

1.

Her father was not waiting for her.

She looked up the track toward the station and saw a tall man standing on the tiny platform. He jumped down and ran to meet her.

He grabbed her in a bear hug, put her from him, kissed her hard on the mouth, then kissed her gently. ‘Not here, Hank,’ she murmured, much pleased.

‘Hush, girl,’ he said, holding her face in place. ‘I’ll kiss you on the courthouse steps if I want to.’

The possessor of the right to kiss her on the courthouse steps was Henry Clinton, her lifelong friend, her brother’s comrade, and if he kept kissing her like that, her husband. (9)

2.

‘Aunty, I’m not staying home, and if I did Atticus would be the saddest man in the world… but don’t worry, Atticus understands perfectly, and I’m sure once you get started you’ll make Maycomb understand.’

The knife hit deep, suddenly: ‘Jean Louise, your brother worried about your thoughtlessness until the day he died!’

It was raining on his grave now, in the hot evening. You never said it, you never even thought it; if you’d thought it you’d have said it. You were like that. Rest well, Jem.

She rubbed salt into it: I’m thoughtless, all right. Selfish, self-willed, I eat too much, and I feel like the Book of Common Prayer. Lord forgive me for not doing what I should have done and for doing what I shouldn’t have done—oh hell.

She returned to New York with a throbbing conscience not even Atticus could ease.

This was two years ago, and Jean Louise had long since quit worrying about how thoughtless she was, and Alexandra had disarmed her by performing the one generous act of Alexandra’s life: when Atticus developed arthritis, Alexandra went to live with him. Jean Louise was humble with gratitude. Had Atticus known of the secret between his sister and his daughter he would have never forgiven them. (31)

3.

She sat up. ‘I don’t know if I can tell you, honey. When you live in New York, you often have the feeling that New York’s not the world. I mean this: every time I come home, I feel like I’m coming back to the world, and when I leave Maycomb it’s like leaving the world. It’s silly. I can’t explain it, and what makes it sillier is that I’d go stark raving living in Maycomb.’

Henry said, ‘You wouldn’t, you know. I don’t mean to press you for an answer—don’t move—but you’ve got to make up your mind to one thing, Jean Louise. You’re gonna see change, you’re gonna see Maycomb change its face completely in our lifetime. Your trouble, now, you want to have your cake and eat it; you want to stop the clock, but you can’t. Sooner or later you’ll have to decided whether it’s Maycomb or New York.’

He so nearly understood. ‘I’ll marry you, Hank, if you bring me to live here at Landing. I’ll swap New York for this place but not for Maycomb.’ (75/76)

4.

Jean Louise followed him in the living room. When the front door slammed behind her father and Henry, she went to her father’s chair to tidy up the papers he had left on the floor beside it. She picked them up, arranged them in sectional order, and put them on the sofa in a neat pile. She crossed the room again to straighten the stack of books on his lamp table, and was doing so when a pamphlet the size of a business envelope caught her eye.

On its cover was a drawing of an anthropophagous Negro; above the drawing was printed ‘The Black Plague.’ Its author was somebody with several academic degrees after his name. She opened the pamphlet, sat down in her father’s chair, and began reading. (101)

5.

She did not stand alone, but what stood behind her, the most potent moral force of her life, was the love of her father. She never questioned it, never thought about it, never even realized that before she made any decision of importance the reflex, ‘What would Atticus do?’ passed through her unconscious; she never realized what made her dig in her feet and stand firm whenever she did was her father; that whatever was decent and of good report in her character was put there by her father; she did not know that she worshipped him. (117/118)

6.

Atticus turned to her. ‘Scout, you probably don’t know it, but the NAACP-paid lawyers are standing around like buzzards down here waiting for things like this to happen…’

‘You mean colored lawyers?’

Atticus nodded. ‘Yep. We’ve got three or four in the state now. They’re mostly in Birmingham and places like that, but circuit by circuit they watch and wait, just for some felony committed by a Negro agains a white person—you’d be surprised how quick they find out—in they come and… well, in terms you can understand, they demand Negroes on the juries in such cases. They subpoena the jury commissioners, they ask the judge to step down, they raise every legal trick in their books—and they have ’em plenty—they try to force the judge into error. Above all else, they try to get the case into a Federal court where they know the cards are stacked in their favor. It’s already happening in our next-door-neighbor circuit, and there’s nothing in the books that says it won’t happen here.’ (148/149)

7.

‘For years and years all that man thought he had that made him any better than his black brothers was the color of his skin. He was just as dirty, he smelled just as bad, he was just as poor. Nowadays he’s got more than he ever had in his life, he has everything but breeding, he’s freed himself from every stigma, but he sits nursing his hangover of hatred…’ (197)

8.

‘Henry, how can you live with yourself?’

‘It’s comparatively easy. Sometimes I just don’t vote my convictions, that’s all.’

‘Hank, we are poles apart. I don’t know much but I know one thing. I know I can’t live with you. I cannot live with a hypocrite.’

A dry pleasant voice behind her said, ‘I don’t know why you can’t. Hypocrites have just as much rights to live in this world as anybody.’

She turned around and stared at her father. His hat was pushed back on his head; his eyebrows were raised; he was smiling at her. (234/235)

9.

‘Atticus, I’m throwing it at you and I’m gonna grind it in: you better go warn your younger friends that if they want to preserve Our Way of Life, it begins at home. It doesn’t begin with the schools or the churches or anyplace but home. Tell ’em that, and use your blind, immoral, misguided, nigger-lovin’ daughter as your example. Go in front of me with a bell and say, ‘Unclean!’ Point me out as your mistake. Point me out: Jean Louise Finch, who was exposed to all kinds of guff from the white trash she went to school with, but she might never have gone to school for all the influence it had on her. Everything that was Gospel to her she got at home from her father. You sowed the seeds in me, Atticus, and now it’s coming home to you–‘ (248)

10.

Dear goodness, the things I learned. I did not want my world disturbed, but I wanted to crush the man who’s trying to preserve it for me. I wanted to stamp out all the people like him. I guess it’s like an airplane: they’re the drag and we’re the thrust, together we make the thing fly. Too much of us and we’re nose-heavy, too much of them and we’re tail-heavy—it’s a matter of balance. I can’t beat him, and I can’t join him–’

‘Atticus?’

‘Ma’am?’

‘I think I love you very much.’

She saw her old enemy’s shoulders relax, and she watched him push his hat to the back of his head. ‘Let’s go home, Scout. It’s been a long day. Open the door for me.’ (278)