Faith, Power, and Survival: What Ruled Life in Early-Medieval England

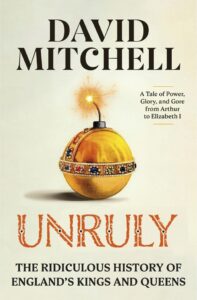

David Mitchell Considers the Less-Than-Illustrious Origins of the English Crown

For me, the misty, dark, unknowable aura of fifth-, sixth- and seventh-century Britain is an enormous draw. Murkiness with a fleeting glimpse of gold. A crown, a sword, a hoard of Roman coins buried by a rich Romano-Briton fleeing his villa in panic…

What was that movement in the fog? A dragon, a dinosaur, a galley full of legionaries hurrying away? The sense of mystery and loss is overwhelming, long before anyone thought of inventing King Arthur.

Hwaer cwom mearg? Hwaer cwom mago?

That’s the Anglo-Saxon language, also known as Old English. It contains hardly any words inherited from Brittonic, which suggests there was eerily little cordial interaction between the Anglo-Saxons and the people they displaced. It’s a snippet from a poem called “The Wanderer” that’s preserved in a tenth-century manuscript but is believed to have been written much earlier. It’s from a bit that translates as this:

Where is that horse now? Where the rider? Where is the hoard-sharer?

Where is the house of the feast? Where is the hall’s uproar?

There’s a powerful sense of missing something, which is a strangely sophisticated emotion to have been preserved for us from what, in our terms, seems like such a primitive and poorly documented culture. Longing and bereavement are surprisingly high in the mix, compared to, say, glory or sex or anger. From our perspective, this little medieval society is barely getting started and yet it’s already steeped in as much moist-eyed nostalgia as last orders at a British Legion club on the anniversary of VE Day.

“The work of giants is decaying,” laments another poem, “The Ruin.” It’s reflecting on some crumbling Roman buildings, probably those in Bath. “Bright were the castle buildings, many the bathing-halls, / high the abundance of gables, great the noise of the multitude, / many a meadhall full of festivity, / until Fate the mighty changed that.”

The true roots of English kingship are therefore so far away from the Arthurian ideal it’s actually funny.

“A meadhall full of festivity” sounds a bit downmarket for a Roman night out, and the reference to “castle buildings” is poignant. Magnificent though they are, the buildings aren’t fortified. They didn’t need to be for most of Roman rule. The Romans established reliable public order, a feat not achieved again in Britain for well over a thousand years. This was a luxury the Anglo-Saxons couldn’t imagine.

Still, the point is well made. I suppose it’s hard to live amid so much decaying infrastructure without feeling a bit glum.

The good news

Some people managed it, though. King Ceolwulf of Northumbria, for example, and his favorite historian, the Venerable Bede. They lived in the late seventh and early eighth centuries and they’re quite upbeat about life. Plus they definitely existed. You can take that as read from now on. The mists of time have lifted considerably.

Bede is one of the main mist-lifters. He was a monk in the abbey of Jarrow in Northumbria and his Ecclesiastical History of the English People was the most famous thing to come out of Jarrow until a march protesting against unemployment in 1936. Bede’s book predates the march by a cool 1,205 years and is one of the main reasons we know anything at all about Dark Age England. He dedicated it to the King of Northumbria at the time, Ceolwulf.

Bede and Ceolwulf are also both saints. I don’t disapprove of Ceolwulf ’s kingly sainthood as much as Edward the Confessor’s, because he abdicated in 737 and lived as a monk for the rest of his life, so he put the hours in sanctity-wise. As did Bede, though the soubriquet Venerable seems to have stuck to him despite achieving higher-ranking saintly status. These things happen. People never really said “Admiral Kirk.”

I have genuinely literally read Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. So you don’t have to. I’d take me up on that if I were you—it may be important but it’s boring. It was written in Latin but an English translation was on the reading list I was given before going to university, so I gave it a go.

In my nineteen-year-old arrogance, what I felt was silly about Bede was that he characterized an age of comparative barbarism and misery as one in which humanity had advanced. He only did this, ridiculously it seemed to me then, because it was a good period for the church, an institution with which he was obsessed. In England, for the hundred years or so before he wrote his history, Christianity had been on the march. That’s why Bede didn’t see the situation in the same bleak terms as whoever wrote “The Wanderer” and “The Ruin.” I felt he was just plain wrong.

Looking back, I realize I was a bit hard on him. Religion both bored and unsettled me, and yet my history teachers were constantly exhorting me not to ignore it. In an A-Level history essay, I was taught, there should always be at least one paragraph on the church. I would dutifully stick one in but I didn’t really get it. I was an agnostic who didn’t like thinking about religion because I hoped there was a God but didn’t have the confidence to commit. Plus the trappings of religion felt a bit embarrassing and weird, like properly putting on a French accent when saying things in French.

My religious views haven’t significantly moved on, but what I am slightly more capable of understanding is that, the existence or non-existence of God notwithstanding, religion is real and powerful and not just something from the olden days. Moreover, in the olden days, it was, in pretty much every society, a bigger deal than we can possibly imagine.

Christianity, for Bede, wasn’t merely something he was massively into, or he solemnly exhorted other people to adhere to, it was everything. It was the real underlying truth of existence, like science is today. It was very much not like religion is today, even for those who are very religious. If we don’t accept that, we can’t begin to understand the times he lived in and the attitude he took.

So, for him, a history of England that wasn’t entirely focused on the spread of the Christian faith would be pointless, because nothing else mattered. This was a prevalent view at the time and one that gave a brutal existence meaning, purpose and hope. I’m thirty years nearer the grave than when I first read Bede and much less confident in rejecting this worldview.

The bad news

The Romans had been Christian by the end. Originally they’d been polytheistic and inclined to use Christians as lion food, but in 313 the Emperor Constantine put a stop to all that and declared he was a Christian himself. Soon Christianity was the empire’s dominant religion, which meant that the Romano-British were Christian—hence King Arthur was Christian, even though he didn’t exist. Over on the continent, Roman rule may not have survived but Roman religion did. Tribes like the Goths and the Franks were content to live in Roman cities and were soon worshipping the Romans’ lovely big single God. Despite repeatedly sacking Rome itself, these upwardly mobile barbarians were keen to live an increasingly Roman life. It was as if they were collectively willing into existence the expression “When in Rome.”

It was different in Britain. The invading Anglo-Saxons weren’t interested in Jesus or a free limoncello. The Britons were driven west, some remaining Christian and some reverting to a sort of iron age paganism, cities were abandoned and the newcomers settled down to a rural existence throughout the south-east of the island, hurling the occasional Roman brick at one another.

The Anglo-Saxons stuck with the form of paganism they’d brought over from the continent, which was a nice little bunch of gods who, as a helpful mnemonic, the days of the week are named after. There’s Woden, king of the gods and god of wisdom—beardy guy with a cloak—after whom Wednesday is named. Then Thunor, their version of Thor, who you might know from the Marvel Universe. He’s god of thunder, which feels like a comparatively small brief, and the etymological root of Thursday.

Then it’s Frigg. I don’t know if the 1970s expression for wanking derives from this goddess’s name—though it seems unlikely as her portfolio includes marriage and childbirth—but the word Friday definitely does and I think we can all agree that the end of the working week is a lovely time for a jolly good frigg. The god of war, Tiw, accounts for Tuesday. Sunday and Monday are the sun and the moon and, weirdly, Saturday is named after the Roman god Saturn, which feels incongruous—a bit like having a parish church called St Mohammed’s.

The veneer of legitimacy was retrospectively applied in order to keep hold of all the power and wealth.

Back to the mortals: whatever the actual names of those early Anglo-Saxon big shots, it seems unlikely that any of them were kings in the sense we understand the word. What probably happened is that the new settlers appropriated areas of land and then, people being reliably unpleasant, some of those settlers would start pushing others around, demanding “tribute” and offering “protection.” Gradually, by the same method used by drug gangs to divide up LA, a system of government emerged.

The local hard guy had to stay in with the provincial hard guy who had to curry favor with the regional hard guy. It was out of this unjust and lawless maelstrom of violence that the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms coalesced. The kingly legitimacy affected by the relatively settled handful of rulers and regimes that were in existence by Bede’s day is no more respectable than a mafia boss adopting the title “Don.”

It’s just dressing up a system based on violence in order to economize on violence. If you can get people to start calling you “sire” and obeying you because they think that’s the way of the world, or somehow right and proper and endorsed by God or the gods, then you don’t have to raise so many bands of heavies or armies and incur all the risks and costs involved in asserting your supposed royalty at the point of a sword or knuckle.

In case this isn’t sounding grim enough, in the 530s–550s there was a period of extreme cold weather, famine and plague. A series of volcanic eruptions in (what is now) Iceland threw up dust clouds that blocked the sun and made the crops fail all over Europe. Outbreaks of plague followed, probably because everyone who hadn’t starved to death was hungry and cold and sad. All this suffering must have hastened the process by which power was consolidated into fewer and nastier hands. Many desperate people will have accepted the protection offered by anyone tough with a bit of spare food.

The true roots of English kingship are therefore so far away from the Arthurian ideal it’s actually funny. The notion that pious legitimacy was the foundation of the institution is totally false. Everything those early kings possessed they, or their ancestors, had either stolen or demanded with menaces.

The veneer of legitimacy was retrospectively applied in order to keep hold of all the power and wealth.

By the late sixth century and early seventh, pretending to be a king was all the rage. The vague regions of strongman influence started to coalesce into kingdoms and the idea of a bretwalda emerged. The bretwalda, which literally means either “wide-ruler” or “Britain-ruler,” was supposedly the dominant Anglo-Saxon king at any given time. We don’t know if the term was used contemporaneously—it may be a ninth-century invention—but the notion of being a dominant ruler must have been understood. It would have been the gold medal in the Olympics of unpleasantness that these violent men were competing in.

Rulers’ status was all about power deriving from violence, combined with a growing sense that a bit of regal showiness helped keep inferiors in their place and intimidate rival kings. So they energetically asserted their importance in other ways. That’s what the elaborate burial at Sutton Hoo was all about. They also built huge wooden halls, full of booze and smoke and warriors. As you can imagine, they burned down, or were burned down, with tedious regularity, but they were major symbols of the new kings’ power.

A king could put a roof over your head, at least for a few hours, and keep you warm and fill your stomach. In those bleak days, that was all it took. Rather poignantly, the modern English word “lord” derives from the Old English hlaford meaning “bread-giver.” In Roman times, there’d been circuses too.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Unruly: The Ridiculous History of England’s Kings and Queens by David Mitchell. Copyright © 2023. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

David Mitchell

David Mitchell is a British comedian, actor, writer, and TV personality, part of the comedy duo Mitchell and Webb, best known in the U.S. for the TV cult classic Peep Show and the Ben Elton-penned historical comedy Upstart Crow, which also became a West End hit. He writes articles for The Guardian and Observer.