Continual Self-Revision: Bee Sacks on Coming Out As a Nonbinary Author

“I have become a text that revises themself, that will revise themself every day, every day until the last day.”

This is a story that ends with my name and begins, I’m sorry to say, on TikTok. In early 2020, I was spending a lot of time on my phone. This was a sweet if scary time in my life: I’d finished my MFA and my agent had just sold my first novel. All my talent and potential would soon be measured against reality. Of course, I melted into Tik Tok.

At the time, the app was unique for the freakishly sensitive algorithm that curated the so-called “for you” page. Very quickly, mine was filled with newly-out adult women who’d spent their whole lives assuming they were straight. How weird for this to end up on my fyp, I thought to myself. Me! A straight woman. Almost immediately, my scrolling began to yield videos of women explaining how “weird” they had found it that their fyp began centering newly-out lesbians until—surprise!—they themselves came out as queer.

That spring, I celebrated my first pandemic Passover in isolation with my latest boyfriend. He was a good person. Most of my boyfriends had been. Whatever grief and resentment welled up in me, I’d always thought that was love. For weeks, this boyfriend was the only person I touched, the only person I sat on a couch to read with, the only person I watched TV with.

The more I wrote, the more I suspect that the words are not the truth, but they can point us toward the truth.By summer, I had come out as gay.

*

Everyone was confused. My life had many cool and kind queer people, all of whom were happy for me but a little taken aback. “Do you have someone?” they asked, incredulous. I wished I did have a girlfriend to hide behind. It would be so much simpler to tell a love story, a story of being seduced, flipped. But I was telling a more abstract story involving language.

On Tik Tok, I had learned new words that began to peel apart my previously held conflations of genitalia with gender with presentation with orientation. Amab, afab, masc, femme, top, bottom—none of these words necessarily anticipating another, as I had always imagined.

I had always assumed I was a straight woman because I enjoyed being penetrated in sex. That’s what made me straight, wasn’t it? Didn’t lesbians not want that? Wasn’t it all some kind of hazy, hard-to-picture soft rubbing that surely satisfied people less brutal and messed up than me? A variety of Tik Toks about strapping and power differentials revealed to me that no, penetration did not necessitate any particular orientation.

But was finding words that would allow me to revise one identity (straight woman) into a queer one (femme bottom?) enough to make me queer? I went on long pandemic walks with my dog, Pupik, up and down the hills of our neighborhood. In my head, sound bites from Tik Tok swirled—bored in the house bored, bitches off the xans, caught in a bad romance, Wells Fargo, wipe wipe, no-na-na-no-no, her sister was a witch, davinki?!—background noise to the question I was too afraid to ask any living person I knew: wasn’t it too late? Maybe I’d lived so long in the straight world that it lived inside me. I was 34 years old. Too late to learn how to bring pleasure to anyone other than a cis man. Too late, too late.

In a training about how to talk to other white people in our lives about abolition, a member of White People 4 Black Lives asked the group to consider, What is your stake in liberation? Who might you be outside of the structures of power you were raised in? I had spent my adult life in militantly nationalistic, heteronormative, carceral states, from America to Israel. If I were free, if we were all free, who would I let myself be?

I began to language myself out of a trap, like a hero in a myth solving a riddle.

*

By summer’s end I was eating pussy, and that first long pandemic winter, my first novel was published. City of a Thousand Gates. The back flap of the book told readers about the author, Rebecca Sacks: She lives in Los Angeles with her dog, Pupik.

I revised myself. Changed the bios on my social handles to make clear my queerness, changed the settings on my dating apps. Rebecca Sacks (she/her) is a queer writer. She lives in Los Angeles with her dog, Pupik.

A year went by. I was manipulated by a fuck-they, charmed by a butch, accidentally wore matching jumpsuits on a date with a transfemme babe, had my heart broken by a lesbian who dressed like Weird Al. I thought of myself as a seasoned dyke. I was out, meaning, I was legible.

So much of writing is having the courage to begin again. A new draft, a new story, a new day of making new sentences. When Tik Tok began showing me videos of newly-out queers who thought they were done coming out once they came out as gay until—uh oh!—gender came scratching at the door, leading them to nonbinary and trans identities, I felt exhausted. Please no, I thought. It’s too much. I’ve changed my whole life, found new words. That’s enough, let it be enough. No matter that when I heard people talk about me—She, she, she lives in LA with her, her, her dog, Pupik—I could feel myself double-take, like hearing a piano hit the wrong note.

It’s too late, I told myself. The young in one another’s arms, changing their pronouns every other week, but not you, Rebecca, not you. You are 36 years old. It’s too late.

*

I went on a walk with a trans-masc friend. One of the first people I’d ever met who used they/them pronouns. I remember being so afraid, when we’d first met, that I would mess their pronouns up and in doing so reveal something bad about myself.

“You identify as a lesbian, right?” Becker asked. They have an easy, open demeanor. Around them, you feel that there’s nothing you could say that would make them hate you.

“Yeah, I mean, currently,” I told them. Pupik ran ahead then circled back, joyfully off leash.

“Okay, my classmate might reach out to you.” Were they setting me up on a date? A felt a tiny surge of disappointment that I actively ignored. “She’s doing some therapy project on the lesbian identity.” Becker was training to be a therapist to work with trans kids and their families.

“There’s a lesbian shortage?”

“I only know nonbinary lesbians,” they laughed. A voice growing deeper each time we met.

I didn’t tell them then, but this was the first time I’d ever heard the phrase nonbinary lesbian. I didn’t know you could be both.

A few weeks later, I came out again. This time as nonbinary. A new pronoun roll out. “We get training for this at work,” my mom told me proudly. “Your gender identity is part of your human rights.” (We’re Canadian.) Other women in my life were more resistant. “It’s just not grammatically feasible,” a dear friend and fellow writer told me. As if neither of us had ever chosen to write in sentence fragments.

*

A year after my first book was published, the paperback came out. By that time, I had updated my website to reflect new pronouns: she/they.

My pronouns continued to shift when I realized that if I listed my pronouns as she/they it meant that only extremely dedicated queer people would bother using “they” at all. Odd that at the same time, I was writing a second novel about a woman who is deciding between self-determination and assimilation into ideology. Or maybe not odd—to be writing an alternate version of myself. In the proofs for that second novel, I made tweaks to the author bio that were likely invisible to most people but monumental to me. About the author, Rebecca Sacks (they/she): They live in Los Angeles with their dog, Pupik.

What the author bio did not say was that I had begun to go by a new name. Bee, pulled from the letters of my given name. More than that, I’ve always loved the letter “b.” The Torah begins with the Hebrew equivalent, bet, second letter of the alphabet. Why not start Genesis with the first letter of the alphabet, aleph, the sages wondered. I suspect the Bible knows what any storyteller knows—a story never starts at the beginning. Bee, in medias res. Bee, a revision.

“Will you ask your publisher to change your name on the book?” Becker had asked me before the second novel came out.

I think that I do not want to come out so much as endlessly reinscribe myself, my words, my names.I felt such tremendous dread at the question. I was scared. Scared that I was changing too much, that it would alienate people who had met me in another form, that it would be too confusing for readers, that it would destroy whatever branding I’d managed to achieve for my old name over the past decade of writing under it, that I’d been ceding to the Other Rebecca Sacks (an accomplished pianist in Boston that I have always felt a one-sided rivalry with).

“No, it’s too late,” I said. It’s always too late. I’m 34, I’m 36, I’m 37, it’s too late, it’s too late. “I’ll just have a reverse pen-name.” I would live as Bee and write as Rebecca. Simple as that.

*

Becker and I had loved each other for a long time before we finally got together. They are the first person to have me as Bee, which I think means, to have me fully.

I’ve erased Tik Tok. At night, Becker and I lie on the couch, reading with our feet touching. With Becker, sometimes I am a boy. The old words that meant so much to me—top, bottom, femme, masc—have faded. Like how when I write, parts of the story that are necessary as a kind of scaffolding in early drafts begin to disappear in later drafts. What’s taken its place is something more fluid, unbound, and impossible to define. Maybe, at last, a little beyond words: the sacred place where two bodies reinvent themselves endlessly.

They call me many names. The more I wrote, the more I suspect that the words are not the truth, but they can point us toward the truth. The name I chose made me more legible to myself, makes me more legible to you. What does it mean for me to introduce myself as Bee? To say, My pronouns are they/them? I think it is my way of telling you—whoever you are—how I want to be loved. These are the words you can use to love me.

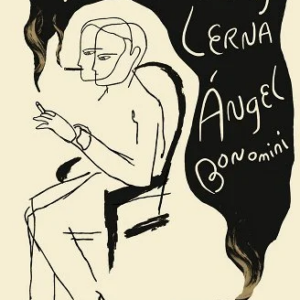

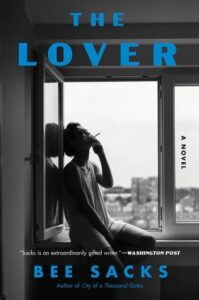

It was never too late. On May 14, the paperback edition of my second novel, The Lover, will be published. My name is on the cover: Bee Sacks.

*

What I am about to say is specific to me. Please do not transpose this sentiment onto someone else’s deadname, someone else’s experience. But me, I love seeing the evidence of myself as a layered, revising text. I look at my books side by side. From she/her to she/they to they/she to they/them, from Rebecca to Bee. These changes do not cancel each other out but rather complicate and reimagine each other. I am a text that I am writing and rewriting. A palimpsest. Sometimes, in inscribing my books at readings, I will alter the cover, using a pen to reform Rebecca as Bee. I love the evidence of this change. I love the marks left behind.

The narrative of coming out is based on a legibility that is not always safe, especially for QTBIPOC. We have not made a world in which it is safe for everyone. More and more, I feel uninterested in legibility. I do not want to be a single word so much as a palimpsest—an endless reinscription of words, names, I want to revise myself, layering one text on top of the other like an ancient palimpsest.

I think that I do not want to come out so much as endlessly reinscribe myself, my words, my names, and soon—I’m becoming certain of this—my own body. I have become a text that revises themself, that will revise themself every day, every day until the last day. Watch me.

__________________________________

The Lover by Bee Sacks is now available in paperback from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.