Celebrating 25 Years of Poetry in Motion

Writing Back to a Legacy, 200 Plus Poems Strong (and Counting)

When I enter a New York City subway car, I first scout for an empty seat. But almost simultaneously, I look for Poetry in Motion posters. Riding the rails with the likes of former Poet Laureate Billy Collins or current Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith is only part of the fun—I also love to speculate about the associations the poems might summon for other straphangers, who number nearly six million every day.

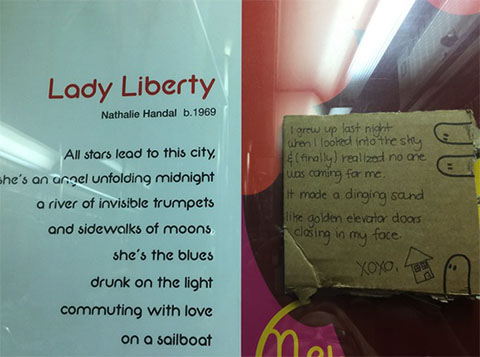

“Lady Liberty” by Nathalie Handal

“Lady Liberty” by Nathalie Handal

Last December, I was delighted to look down the aisle on a not-too-crowded 6 train and spot a piece of cardboard taped to Nathalie Handal’s “Lady Liberty.” On it was a handwritten poem—no title, no name. But following “XOXO,” there was a signature of sorts: three finger people with dots for eyes beside a simply-drawn house. A love poem back to Poetry in Motion, I quickly and arbitrarily concluded.

A love letter to Poetry in Motion on the 6 train

A love letter to Poetry in Motion on the 6 train

Poetry in Motion was founded in 1992 as a joint effort between the Poetry Society of America and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Inspired by a similar program in the London tube, it aims to ignite a broad range of conversations in public transportation. Since its New York debut, Poetry in Motion has appeared in more than 25 other cities across the nation. A new anthology edited by Alice Quinn, The Best of Poetry in Motion, will include half of the 200-plus poems featured on subways and buses, as well as a history of the collaboration.

Molly Peacock, the president of the PSA at the time of Poetry in Motion’s creation, described the program’s goals in the introduction to an earlier anthology:

Since nationalities representing the entire world ride on New York City’s public transit, we try to reflect that world. We look for poems that will speak to all ethnicities, genders, ages. We look for voices that will stimulate the exhausted, inspire the frustrated, comfort the burdened, and enchant even the youngest passengers.

Following its reboot in 2012 under the leadership of Sandra Bloodworth, the program pairs art commissioned by MTA Arts & Design with poetry; each quarter, two poems are displayed throughout the transit system. According to MTA estimates of subway ridership, these reach 1.7 billion potential readers annually. Poems can also be found on roughly five percent of MetroCards, putting millions of poems in riders’ pockets every year. As New York Times columnist Jim Dwyer noted, the MTA “could claim to be the most successful publisher of poetry in history.”

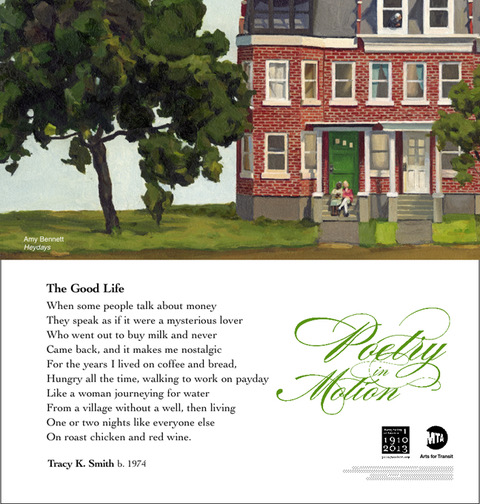

Tracy K. Smith treasured the NYC posters as a MFA grad student at Columbia University as “morsels of ecstatic language to think about and carry with me.” Years later, her poem “The Good Life” was featured in 2013 and is reportedly one of the program’s most popular.

“The Good Life” by Tracy K. Smith

“The Good Life” by Tracy K. Smith

“Having my own poem on display in the trains was an enormous affirmation,” said Smith, who had won the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry the year before. “Even more emphatic was the feeling of community I got whenever I’d receive word from a fellow New Yorker who had glimpsed ‘The Good Life’ on their commute. Your poem touched me. Or, I remember those days of living paycheck to paycheck that your poem describes. Or, I’ve never really read poetry before, but I memorized your poem on my way to work today.”

A year later, “Heaven” by Patrick Phillips received a similarly enthusiastic response—some admirers even looked him up and reached out. A father wanted permission to make t-shirts of the poem for the third anniversary of his son’s suicide. Adults told him how deeply they missed their parents. Several composers wanted permission to set it to music. One woman carried a MetroCard with the poem on the back for a year, then retired it to her bulletin board at work once the card expired.

“Heaven” by Patrick Phillips

“Heaven” by Patrick Phillips

One reader, whose mother had recently died, thanked Phillips for the comfort that his poem provided. After he replied with condolences, she emailed again with this question: I was wondering if I might ask you the inspiration for that poem. If it’s too personal, I understand.

Phillips explained that the poem was inspired by his grief at the fact that his young sons won’t remember his wife’s father, who died “too young, from really merciless prostate cancer,” and by his envy of Renaissance poets George Herbert and Ben Jonson’s faith in a heavenly reunion. Moved, he ended his reply, “And now I’m all teary on my commute home!”

Others expressed their appreciation for a moment of reflection on their way back from work. “Thank you for creating this masterpiece that I enjoy ever so often when I get on THAT car on THAT Queens-bound A train on my way home after a long hard day of living in New York City,” one such reader wrote Phillips.

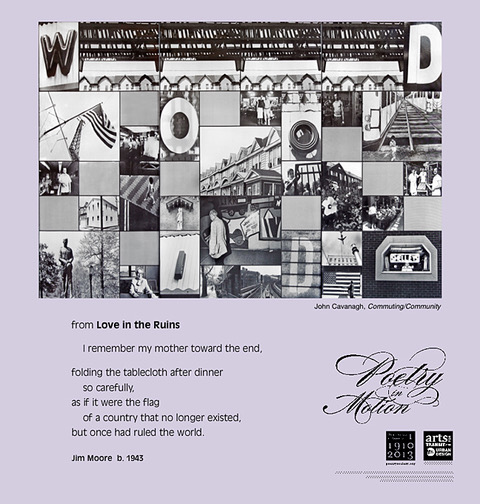

Jim Moore, who lives in Minneapolis, was surprised by how many friends and strangers emailed him about his contribution to the project, “Love in the Ruins.” During a visit to New York, his wife introduced him to an old acquaintance as a poet. Without realizing the connection, the friend relayed how she burst into tears reading a subway poem about a mother folding a tablecloth—his poem. “It was an amazing moment,” Moore said.

From “Love in the Ruins” by Jim Moore

From “Love in the Ruins” by Jim Moore

Since 2013, Moore’s had an ongoing email relationship with a woman from Connecticut who he has never met. She told him that she tucked the poem into her calendar holder as a reminder of her deceased mother and how made dinners as special as holiday feasts every night. “Yesterday was one of those times,” she emailed Moore in July. “I sat down, read it, teared up… The memory of the subway, my finding you, and your incredibly generous response remains so lovely in my mind.”

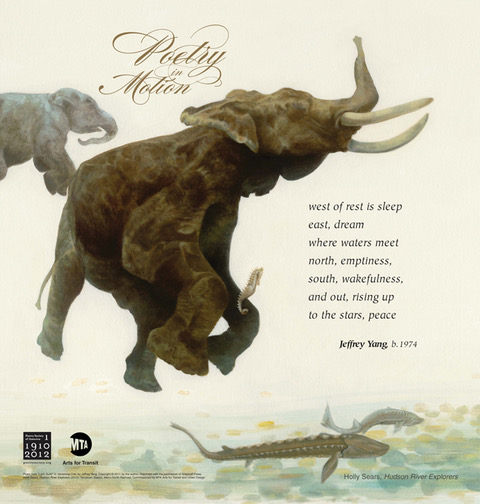

Jeffrey Yang, whose untitled poem from the sequence “Lyric Suite” was featured in 2012, was also amazed by the range of reactions to his work. “One film director has used it in his new movie, a musician has set it to music, many friends have described spur of the moment discussions with other train riders about it, a philosopher started a long online group discussion focused on it, a literary critic used it as an epigraph in her new book, a nun wrote me a glowing note about it, random people still post stills of it on the internet,” he told me. “The list goes on and on and is weirdly astonishing.”

Untitled by Jeffrey Yang

Untitled by Jeffrey Yang

Former Poet Laureate Billy Collins has the distinction of two poem commissions by the MTA: “Grand Central” for the station’s 100th anniversary and “Subway” for the launch of the 2nd Ave Subway. Collins read “Subway” on the Dec. 31, 2016 inaugural ride, which I attended.

“That poet guy must have walked the tracks before. Or he has a good imagination,” said a lanky electrician holding a postcard of the poem as we both exited the station that night. This comment was more than enough to thrill Collins. “The poem intends to draw grateful attention to those very workers,” he explained after I passed the message along.

“Grand Central” by Billy Collins

“Grand Central” by Billy Collins

My favorite pairing of visual art and poem is “Primavera,” a mosaic by Raúl Colón at the top of a stairway at the 191st Street 1 Train stop. That was my exit when I coached eighth graders at The Equity Project with their application essays for high school. As a warmup, I’d suggest they substitute as many nouns as they wanted in “Ragtime” by Kevin Young to say something unique about themselves, which sometimes extracted compelling details for their essays.

“Ragtime” by Kevin Young

“Ragtime” by Kevin Young

Other teachers have told PSA how they’ve used the Poetry in Motion poems in their classroom. A minister asked for permission (not that he needed it) to use one of the poems in his sermon. A nun wanted copies of another for senior citizens. Parents have described how they talk about the poems with their children.

“It’s a big part of how Ruby (age 6) learned to read: we practice on those poems,” one parent told. “We purposefully look for a subway car with [Poetry in Motion] posters in it, and we talk about them in the morning,” another wrote to PSA. “It brings my son and I closer together.”

Although my conclusion about the cardboard taped to “Lady Liberty”—that it’s a love letter to Poetry in Motion—is just conjecture, it’s not an unfounded assumption. The project has impacted countless people, writers and passengers alike. Whoever the unnamed poet is, they’re undeniably talking back to a legacy, 200 plus poems strong and counting.

__________________________________

Many of the poets featured in the new anthology will read their contributions and relay their stories on October 25 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts Dorothy and Lewis B. Cullman Center at Lincoln Center. Poets include Billy Collins, Aracelis Girmay, Major Jackson, Ada Limón, Jim Moore, Paul Muldoon, Marilyn Nelson, Patrick Phillips, Katha Pollitt, and Kevin Young. Admission is free but reservations required through Eventbrite.

The Poetry in Motion atlas on the poetrysociety.org website offers a sampling of poems from 25 cities, searchable by city and poem title. Poet and artists bios available here.