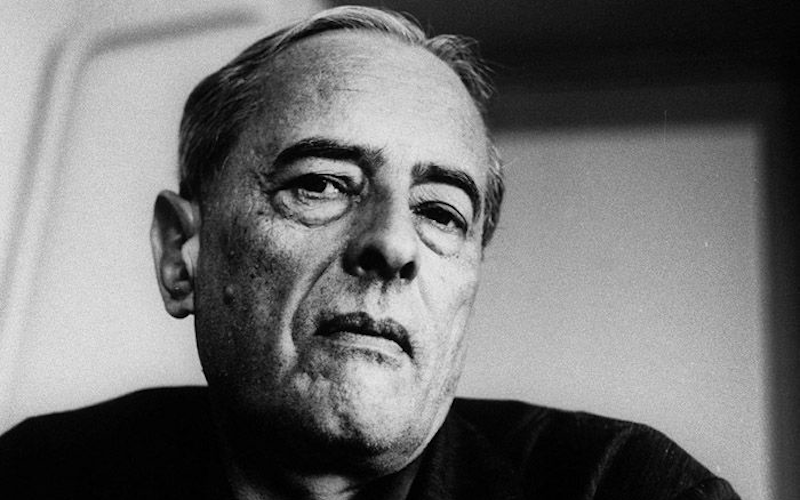

Adam Thirlwell on Witold Gombrowicz's The Possessed

Revisiting a Polish Modernist Classic

No one was better than Gombrowicz at talking about Gombrowicz. It’s possible that his masterpiece is his Diary, which he began writing in the Parisian émigré magazine Kultura in 1953, and continued until he died in July 1969. ‘I must become my own commentator, even better, my own theatrical director. I have to create Gombrowicz the thinker, Gombrowicz the genius, Gombrowicz the cultural demonologist, and many other necessary Gombrowiczes.’ In another brilliant work of self-commentary, Testament, a book-length interview with Dominique de Roux published in 1968, where Gombrowicz considers his entire oeuvre, he comes up with a constant barrage of self-definitions and aphorisms: ‘I consider myself a relentless realist. One of the central aims of my writing is to forge a path through the Unreal to Reality.’ Or: ‘I could define myself as a little Polish nobleman who has discovered his raison d’être in what I’d call a distance from Form (and therefore also from culture).’ But also: ‘Sincerity? As a writer, that’s what I fear above all. In literature, sincerity leads nowhere.’

The persona was all violence and haughtiness, but at the same time this violence was a product of a total marginalization. He had grown up in Poland in the early twentieth century. In 1933 he published his first book, a collection of stories called Memoirs from the Time of Immaturity (later republished in an expanded version with the new title Bacacay) and entered the world of Warsaw publication: of little magazines and their domestic disputes. Four years later he published a novel, Ferdydurke, and then a year later a play called Yvonne, Princess of Bourgogne. A year after that, in the summer of 1939, he serialized his so-called potboiler, The Possessed, using a pseudonym: Z. Niewieski.

Now, we will come back to The Possessed. But what then happened to Gombrowicz was a catastrophe but also fairy tale of world history. On 29 July 1939 he took the inaugural transatlantic liner from Gdynia in Poland to Buenos Aires in Argentina, a diplomatic voyage to which he was invited by Jerzy Giedroyc, who worked at the Ministry of Industry. (After the war, Giedroyc, in his Parisian version of exile, went on to found Kultura.) Gombrowicz arrived in Buenos Aires on 21 August. Two days later, Germany and the Soviet Union signed the non-aggression pact, and just over a week later Hitler invaded Poland. As scheduled, the liner turned to go back to Europe. Gombrowicz took his suitcases on board and then, just before departure, in a moment of self-preservation, took them back to shore – where he remained, in Argentina, until 1963. The literary life had suddenly become a life of anonymity and poverty.

I cherish this image of Gombrowicz anonymous very much – working a terrible 9-5 career in the Banco Polaco, a European writer lost in Argentina, while the Nazis annihilated central Europe, including his friends from literary bohemia, like Bruno Schulz. With some Latin American writers Gombrowicz worked on a Spanish translation of Ferdydurke – a translation that became legendary partly because of the difficulty of its production: between Latin Americans who spoke no Polish, and a Polish writer who spoke only rudimentary Spanish. It appeared in 1947, and was infinitely ignored in Latin America. Gombrowicz’s next novel, Trans-Atlantyk, was published in Kultura, and therefore only read by its 3000 subscribers. This was why in 1952 Gombrowicz began to write a Diary for Kultura. In it, he would create a personality equal to his lost ambition. It was his only method left to impose himself on the world.

*

What I mean is that, between the Gombrowicz who finally died in the south of France in 1969, a celebrated European novelist, and the Gombrowicz who wrote The Possessedaged 34, in the full typewriter wildness of central Europe, there is this 30-year gap in which he offered up his early writing to the full clarity of his dominating intelligence. It was only just before he died, however, when he compiled a list of key dates and works for Dominique de Roux, that he acknowledged that The Possessed was one of his works at all. The Possessed therefore has the allure of a disowned work, a tacit work – a pulp novel that was written under a pseudonym, written only (so the story goes) for money: as if this novel couldn’t fit into the vast work of self-commentary and explication Gombrowicz had set himself.

Just this once, I think, Gombrowicz was wrong in his auto-analysis. The Possessed is a true planet from Gombrowicz’s galaxy. Out of its high-speed plot emerge many themes of his later self-portrait. It’s true that it poses as some kind of gothic novel, or the parody of a gothic novel. It has a mad prince in a remote and ruined castle, and a haunted room, and a possible treasure. But it also has a strange layer of ultra-modernity: the dance halls and tennis courts of 1930s Warsaw. And anyway, Gombrowicz was always a writer of the fantastical: his art, he pointed out, was based on pure non-sense, on the absurd. To detach The Possessed from the equally parodic stories he wrote in the 1930s, or from the wild opening of Ferdydurke (where a writer who very much resembles Gombrowicz is abducted by a teacher called Pinko and taken back to school), just because its genre is a fantasy genre, is possible only through a feat of impossible engineering. In Testament he looked back on these early works: ‘The formal apparatus I had set in motion was all my own creation. And this apparatus led me by surprise into regions I would never have risked myself if I hadn’t been so high on the absurd, on playfulness, on mystification, on parody.’

Just this once, I think, Gombrowicz was wrong in his auto-analysis. The Possessed is a true planet from Gombrowicz’s galaxy.

The Possessed has one surface plot, which it gradually abandons. This plot concerns the machinations of the mad Prince’s secretary to inherit or steal the Prince’s art collection – a collection which has so far been unaccountably undervalued – so that he can then marry Maja Ochołowska: a beautiful, bourgeois girl who is also a tennis star. Gradually that story is overtaken by a darker narrative, which contains two different forms of haunting. The first form is the ghost of the Prince’s unacknowledged son, whose presence is figured in the uncanny movements of a towel at a kitchen window in the castle:

It was very gently quivering, probably because of a current of fresh air coming from the window. But this motion was strange. The towel wasn’t moving freely in the draught, but quivering, and it was taut. And that made it look as if an invisible hand were holding onto it from below. This motion could not have been the result of air currents – it was a different motion.

The second form is the developing intimacy between Maja, the tennis star, and her new coach, Marian Leszczuk (whose name, until the end of chapter 2, is in fact Walczak – a change apparently determined by a wish to avoid accusations of libel by a ‘real tennis coach named Mr Walczak’, but really, of course, for Gombrowicz to show off the patisserie lightness of his philosophical style). From the moment they meet, Maja and Marian feel a strange frisson of similarity and resemblance, both physical and psychological, that encroaches on them until soon every conversation and interaction feels uncanny.

And at last here we are, inside Gombrowicz’s studio. The Possessed is a fugue on the theme of resemblance. It imagines resemblance as possession by another, and therefore as a state that’s both intoxicating and also to be resisted. There are likenesses everywhere in this novel, all centring on the trio of Maja and Marian and the Prince’s apparently dead and unacknowledged son, Franek. Among them, there are many forms of possession, because there are many ways people can be inhabited by other people: like lust or greed or grief. Everyone is vulnerable to being petrified into a form that belongs to someone else, misshapen by other people’s neuroses and psychoses, or the inherited forms of invisible traditions.

This was the terrible wisdom Gombrowicz discovered in his early works, including Ferdydurke, his novelistic masterpiece – a wisdom partly prompted by the horror of a city’s domestic literary criticism. That city happened to be Warsaw. It could have been anywhere. He had entered the world of publication and found himself deformed, into a subject of conversation and journalism. And so he had been forced into a defining philosophy, a sort of existentialism based on shame and humiliation: ‘Accept and understand that you are not yourself, no one is ever themselves, with anyone, in any situation; to be human means to be artificial.’ And then, as he told the revelation thirty years later to Dominique de Roux:

I wasn’t the only one to be a chameleon, everyone was a chameleon. It was the new human condition, you had to understand this very fast.

I became “the poet of Form”.

I amputated myself from myself.

I discovered the reality of the human race in this unreality to which it is condemned.

And Ferdydurke, instead of helping me, became a grotesque poem describing – as Schulz wrote – the torments of human beings on a Procrustean bed, that of Form.

The other grotesque poem from this era is The Possessed.

*

Yvonne, or the Princess of Burgundy, the play Gombrowicz wrote in the same period – and which was never performed until the years of his post-war European success – was about a prince who meets a woman who disgusts him in every way. Nevertheless, he is so determined to refuse the apparently universal and implacable laws of desire and disgust that he resolves to marry her. The plot then functions the same way Pasolini’s Teorema would function – but an anti-Teorema, a Teorema of the abject. Introduced to the court, Yvonne’s absolute lack of charm or beauty acts as a drastic catalyst on the prince’s courtiers, so that each reveals their own vices and weaknesses – until finally, horrified at the revelations prompted by her mute presence, they all band together to kill her.

In The Possessed, too, people find themselves desiring people who apparently disgust them, just as everyone in the novel finds themselves hypnotized by the uncannily repulsive movement of a towel. Disgust is one of Gombrowicz’s discoveries. It’s also one of his wonderful lessons for the history of the novel. He was a grand stylist whose perception of the artificial and the unreal was so absolute that it included high style itself. In Buenos Aires he gave a talk called ‘Against Poets’, which he reprinted in his Diary. It was written, he announced, against ‘the cult of Poetry and Poets’, but as he continued it becomes obvious that what it’s really written against is our continued miasma of unreality. In poets, he writes,

“not only their piety irritates us, that complete surrender to Poetry, but also their ostrich politics in relation to reality: for they defend themselves against reality, they don’t want to see or acknowledge it, they intentionally work themselves into a stupor which is not strength but weakness.”

Beautifully venomous, true, but earlier on in the talk he had secreted another acidic truth with possibly even larger implications: ‘that all style, every distinct attitude forms itself through elimination and is, basically, an impoverishment.’

Famously, Gombrowicz kept another diary as well as his Diary – a text called Kronos, which functioned as a kind of shadow diary, an everyday record of money and sex and ambition, written almost in note form: the misshapen double of the Diary written for publication. That text only emerged in full in 2013 when it was first published in Polish. In the same way, The Possessed, which only emerged in its entirety in 1990 when the final three chapters were rediscovered, and is now for the first time translated into English with beautiful brio by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, is a kind of shadow novel. Its form is schlock and pulp. Like the prince’s abandoned son, it was almost entirely unacknowledged by its creator. And while it contains irrepressible moments of high literature – if you need an example, the moment at its finale where three bewildered characters are transformed into ‘three speechless question marks’ – it also features gleefully untalented scenes of exposition, with plot information crudely transported to the reader in impossible train conversations and purloined letters. Two major scenes of demonological investigation are detailed descriptions, shot by shot, of a tennis match, like some kind of magazine story for public schoolboys.

But the shamefulness, the pulp and the shlock, is also the mark of its genuine avant-garde originality. A novelist who’s too precious about the creation of a style is not a true novelist because they are not a true person. They are just another ghost of unreality. The Possessed, this novel of mutants and doubles, is mutant Gombrowicz, double Gombrowicz. It’s a modernist text remade with extra gore. It’s so shameful that it belongs to the only true destination of literature, which is the future.

__________________________________

From the introduction to Witold Gombrowicz’s The Possessed, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. Used with permission of the publisher, Fitzcarraldo Editions. Copyright 2023 by Adam Thirlwell.

Adam Thirlwell

Adam Thirlwell was born in London in 1978. He is the author of four novels, and his work has been translated into thirty languages. His essays appear in The New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books, and he is an advisory editor of The Paris Review. His awards include a Somerset Maugham Award and the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; in 2018 he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He has twice been selected by Granta as one of its Best of Young British Novelists. His novel The Future Future is available now from FSG.