A Pilgrimage to the World's Most Famous Manuscript

Coming Face to Face with the Book of Kells

The Book of Kells has been reported stolen twice. The second occasion was in 1874. The account in the Birmingham Daily Post and Journal for November 5 is typical of a large number of similar stories in the press across Britain and Ireland that week: “Trinity College, Dublin, is in despair. One of its chief treasures is missing—viz., the Book of Kells, written by Saint COLUMBKIL in 475—the oldest book in the world, and the most perfect specimen of Irish art, with the richest illuminations, and valued at £12,000 . . . ” It was recounted that the loss was discovered when the Provost of Trinity College had wished to show the manuscript to some lady visitors, and he found that it had disappeared. No one could recall when it was last seen, and the librarian was absent and could not be consulted.

Rumors and whispers flew around, as they can only in universities. The Birmingham Daily Post reveled in a further layer of mystery: “A receipt for the volume signed by a Mr. BOND, purporting to be from the British Museum, has been placed in the hands of the Provost.” Within a week the manuscript was located. The librarian of Trinity College, J. A. Malet, had himself taken it to the British Museum in London for advice on rebinding. The College sent its lawyer to London to demand its return, and the manuscript was hastened indignantly back to Ireland. Those were heady days for Irish nationalism. In 1874 the Home Rule League was founded. Gladstone’s Irish Government Bill was narrowly defeated in 1886. In 1888, the executive committee of the politically charged Irish Exhibition at Olympia in London requested inclusion of the Book of Kells. “It is believed that a satisfactory arrangement may be come to in that respect,” blandly reported the Dublin newspaper Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser on April 25th of that year. It was widely announced in London that the manuscript would be exhibited. This was reckoning without politics. The Board of Trinity College soundly refused: “They do not consider it consistent with their duty to subject such a unique and invaluable national treasure” to exposure in England.

The previous occasion when the Book of Kells was stolen was a little over 850 years earlier, in 1007. We have only one source for this incident and some of its details are ambiguous. The account is in the so-called Annals of Ulster, an ever-updated chronicle partly in Old Irish from the earliest times to the beginning of the 16th century. The original manuscript is also in Trinity College, Dublin. One entry in the narrative for the year 1007 has been loosely rendered something like this: “The great Gospel of Colum Cille was sacrilegiously stolen in the night from the western sacristy of the church of Cennanas. It was the most precious object of the Western world, on account of its covers with human forms. This Gospel was recovered after two months and 20 nights, its gold having been taken off it and with a sod over tablemat.”

“Colum Cille” is Saint Columba (it literally means “Columba of the Church”). “Cennanas” is the old name for the town of Kells, or Kenlis, in County Meath, about 40 miles north-west of Dublin. The westerly storage place of the book—“airdom iartharach” in the original—may mean the western end of the church or it may have been some kind of free-standing treasury to the west of the church. The stated reason for the theft was because of a highly ornamented binding or fitted case, for Irish Gospel Books were commonly enclosed in portable shrines. The original word used in the Annals is “comdaigh”; in other contexts it is usually spelled “cumdach.” Evidently the cumdach at Kells was made of gold and was ornamented with anthropomorphic images, perhaps representing the Evangelists. The robbers were interested only in the value of the precious metal, and they may have been Vikings. The thieves of the Book of Kells presumably stripped it and discarded or buried the worthless text. The two months and 20 nights of its purgatory are exactly double the 40 days and 40 nights of the Gospel account of Christ in the wilderness, or twice the length of Lent. They ended with burial and resurrection.

This “most precious object of the Western world” is now a national monument of Ireland at the very highest level. It is probably the most famous and perhaps the most emotively charged medieval book of any kind. It is the iconic symbol of Irish culture. It is included in the Memory of the World Register compiled by UNESCO. A design echoing the Book of Kells was used on the former penny coin of Ireland (1971 to 2000) and on a commemorative 20-euro piece in 2012. One of its initials was shown on the reverse of the old Irish five-pound banknote. It has been illustrated on the country’s postage stamps. Probably every Irish bar in the world has some reflection of its script or decoration. It is reproduced on millions of tea towels of Irish linen, not to speak of patriotic or souvenir scarves, ties, brooches, beer bottles, cufflinks and tablemats.

The original is displayed in a special darkened shrine now called the Treasury, at the eastern end of the library at Trinity College in Dublin, and over 520,000 visitors queue to see it every year, buying colored and numbered admission tickets to the Book of Kells exhibition. More than 10,000,000 people filed past the glass cases in the first two decades after the opening of the present display in 1992. The daily lines of visitors waiting to witness a mere Latin manuscript are almost incredible. There are signposts to the “Book of Kells” across Dublin. The new tram stop outside the gates of Trinity College is named after the manuscript. No other medieval manuscript is such a household name, even if people are not always sure what it is. I have quite often been asked whether a “Book of Kells” is similar to a “Book of Hours,” and, if so, what is a kell?

The Book of Kells, which simply takes its name from the town which once owned it (and from which it had been stolen in 1007), is a manuscript of the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke and John—in the Latin translation of Jerome, with variations supplemented with a number of traditional prefatory texts before the start of the Gospel of Matthew. It probably dates from the very end of the eighth century.

I arrived in Dublin to see it on an early-morning flight from London, for it is practically within commuting distance, connecting with the airport shuttle bus into the south center of the town. It was a crisp autumnal day, with high clouds in the palest of blue skies. You come into Trinity College through an archway in a classical building called Regent House into what is virtually a miniature city of grand houses and elegant squares. For the Book of Kells you follow signs straight ahead and then to the right, round to the far (south) side of the long 18th-century library building. With slight embarrassment at my presumption, I threaded past the lines of tourists already queuing along the cobbles outside for admission to the Treasury exhibition. You enter and leave the building through the bookshop, for Kells is serious business, like pilgrim shrines of the Middle Ages.

There is no obvious inquiry desk other than the harassed cashiers. I espied a man in official clothing and I asked where I should go for an appointment with Bernard Meehan, the keeper of manuscripts. “Oh, I’ll take you,” he said, with that irresistible Irish lilt. I suspect now that he had actually been sent to wait for me. He led me straight up the main staircase marked “Exit only” directly into the center of the Long Room, as it is called, of Trinity College Library. This is the magnificent polished wooden cathedral of books, built by the architect Thomas Burgh in 1712–32 initially for 100,000 volumes but doubled in the mid-19th century by an upper floor of multiple mezzanine galleries of gilt and leather-bound books from floor to firmament. It is breathtaking. Even my escort paused, to allow the effect to penetrate me properly. “You’ve been here before, I suppose?” he asked. I agreed that I had.

If Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel could have existed in reality, it would have been something like the Long Room of Trinity College. We walked down the length of the room, past marble busts on pedestals and exhibition cases, through barriers of green ropes, to a steep wooden staircase, like something on a sailing ship, in the far left-hand corner. “Mind your head,” said the man, whose name I learned later was Brian. He brought me upstairs into a balcony, where two conservators were working at a table, and through into the reading-room for rare books at the western end, like the sacristry of Kells. Several people were at desks, some of them (I could not help noticing) being made to wear gloves. We, however, turned right and then left again into the open-plan library offices, where Bernard Meehan emerged to welcome me most affably. He has a neatly cropped greying beard, a bit like a friendly Schnauzer dog with glasses. Everyone likes him. He is the kind of person who uses your first name constantly when addressing you.

The Book of Kells is so precious and so immediately recognizable that Bernard explained that it would be inappropriate to allow it into the reading-room. No other manuscript is comparable, not even the Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry, at Chantilly in France. The Book of Kells risks being mobbed, like a pop star or a head of state. The security arrangements around it are necessarily as complex as presidential protection undertaken by the secret services of a great nation. The three of us went out to a secure room in the library in which there could have been be no possibility of accidental interruption.

Earlier that morning Bernard had had a large grumbling humidifier wheeled in to bring the centrally heated environment of the location up to the level for the optimum safety of the manuscript. It was clearly working, for the little window had already misted up with moisture. I was placed at a circular green-topped table, prepared in advance with foam pads, a digital thermometer, and white gloves. “We are ready,” he nodded to Brian, and the two of them went off together to fetch the first volume. I cannot deny that I felt a certain excitement in sitting alone waiting for their return. It had been more than 50 years since I handled my first modest medieval manuscript, at the age of 13, in the Dunedin Public Library in New Zealand. I wondered what I would have thought then if I could have known that I would one day be in Dublin, about to meet the most famous book in the world.

__________________________________

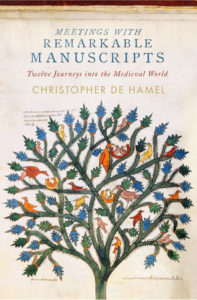

From Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts. Used with permission of Penguin Press. Copyright 2017 by Christopher de Hamel.

Christopher de Hamel

In the course of a long career at Sotheby’s Christopher de Hamel has probably handled and catalogued more illuminated manuscripts and over a wider range than any person alive. Since 2000, he has been Fellow and Librarian of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. The Parker Library, in his care, includes many of the earliest manuscripts in English language and history. He is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Historical Society.