In an essay on the painter Walter Sickert, Virginia Woolf once voiced a surprising preference: “Words are an impure medium; better far to have been born into the silent kingdom of paint.” This turned out to be a running theme. In 2021, David Zwirner put out a collection of her art writing with the wistful title, Oh, To Be a Painter!

Though perhaps “paint > words,” is a surprising sentiment to hear from one of the twentieth century’s greatest authors, Woolf is far from the only writer in thrall to the visual arts. There’s a long list of novels featuring painter protagonists. And in some cases (see: Dorian Gray) a piece of art propels a plot. Less remarked on is the writer-turned-visual-artist phenomenon, presumably born of authors like Woolf who held a candle for the canvas. Or, more than a candle. Yes: here’s the part where I invite you to consider the writer who picks up the brush, pen, or scissors… herself.

Polymathing is a difficult row to hoe, so I take a moment to marvel first at all the artists who work across mediums. But—and at the risk of being gauche—while looking into the hybrid creator, I was curious to see who wore their second hat….the best. So here is a ranked list of art works by mostly-known-as-authors. (Givens, to get them out of the way: obviously, art is subjective, and I am no Jerry Saltz.)

10.

Alexander Pushkin

The beloved Russian novelist Alexander Pushkin was a quintuple-threat. The man wrote books, plays, poems, and music. Biographers also recently discovered that he kept a graphic journal, stuffed with doodles and sketches.

Like this one of of his lover, Anna Alexevyena Olenina.

Though Pushkin never pursued drawing professionally—perhaps he was too busy, between the other four careers—you can see the aptitude here. There’s a clear personality, coming through in the bold line work of his sketches. So I would like to give this busy genius a solid participation trophy, in my imaginary contest.

9.

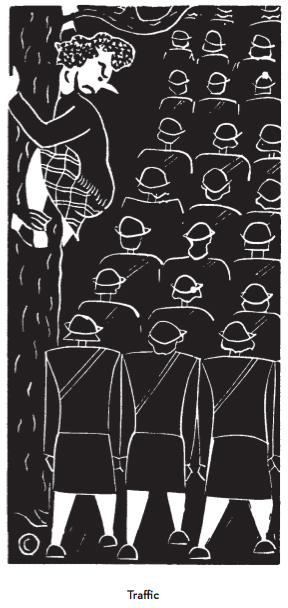

Flannery O’Connor

The fact that the grand dame of the Southern Gothic moonlit as a cartoonist is fairly well-documented. O’Connor spoke often about her drawing practice, which she saw as part of “the habit of art.”

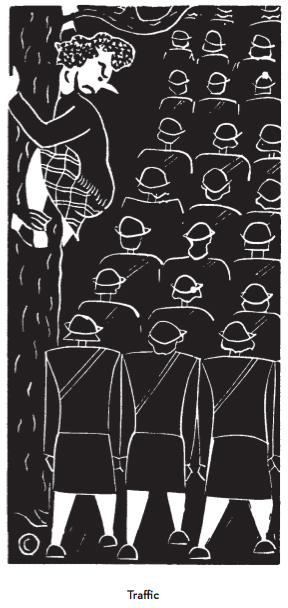

The satirical cartoon series she drew about the women of WAVE (or, Women Appointed for Voluntary Emergency Service) has been the subject of particular fascination. Find one of those panels, below.

I enjoy the snouts! The shoulders! There’s something of Harold Gray’s “Annie” in these woodblock-y curves. But what strikes me the most about this series is the playful sense of humor. Though ever-wry, I don’t tend to think of the lady as a goofball on the page.

Counterpoint: the composition does leave a little to be desired. O’Connor’s aperture on the sketchpad doesn’t feel as tight as it does in, say, “Country People.”

8.

William Makepeace Thackeray

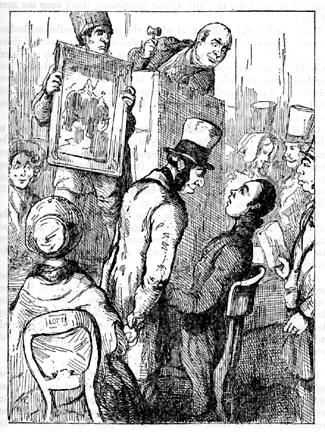

The Victorian wit is one of the few folks on this list who was well-known as a visual artist in his lifetime. Thackers did not hide his second love under a bushel. In fact, many of his pieces accompanied an illustrated printing of his novel, Vanity Fair.

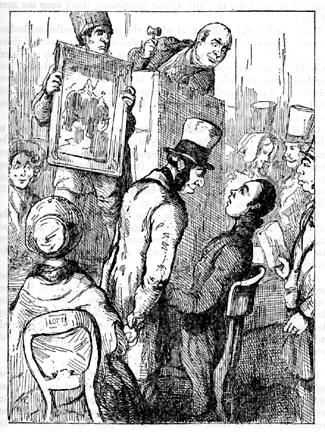

In 1875, the art collector Joseph Grego gathered hundreds of Thackeray’s illustrations and published them in a ridiculously named compendium. Here’s a sample from those files, via The Victorian Web.

Really fun line work, in this “reviewer’s” opinion. But this one’s maybe a little staid, a little claggy. Some of the work seems stranded between caricature and earnest representation.

7.

Franz Kafka

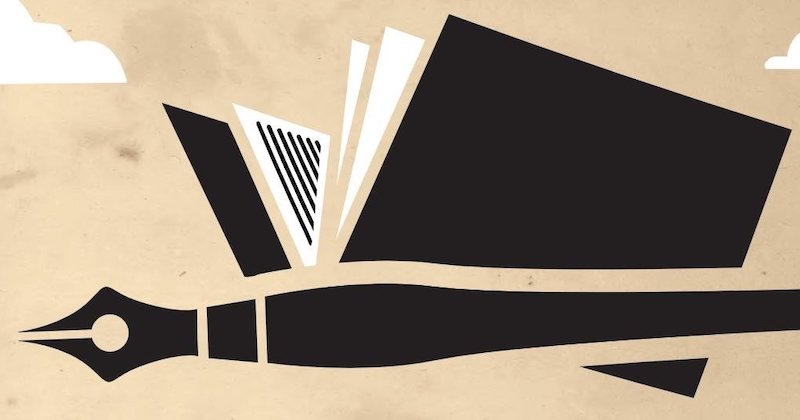

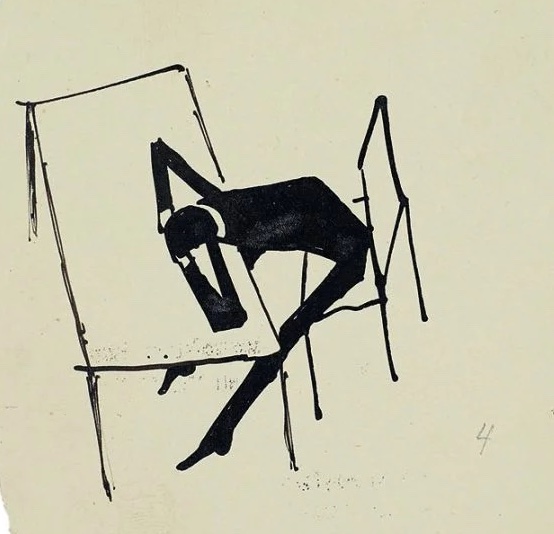

In his own estimation, Kafka was “once a great draftsman,” in addition to being an epoch-defining story writer. His sketches were recently collected in a book, Franz Kafka: The Drawings, which was excerpted in these very pages.

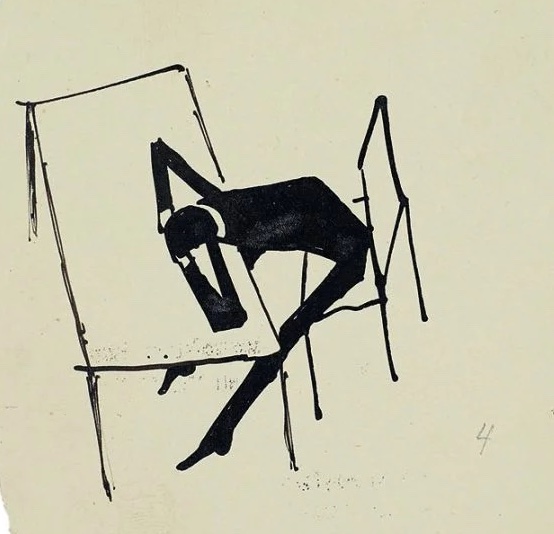

This drawing, from the literary estate of Max Brod, caught my eye.

Kafka’s jagged angles lend themselves to interesting compositions. Which rhymes with his general vibe, in the short fiction. And I’m not sure if I’ve ever seen the anguish of the writing process represented better.

The lines are confident, elegant, dynamic—if a little hasty-feeling. I think the clerk could have been a contender!

6.

Victor Hugo

It’s unclear to me how Victor Hugo had time to draw, given the sheer amount of print matter he produced over his reign as the big literary tuna in 19th century France. But somewhere in between writing to two thousand-plus-page opuses (opi?), and many plays, novellas, and short stories, Hugo honed a real talent for drawing. His son Charles described his work as “often strange, always personal,” and reminiscent of “the etchings of Rembrandt and Piranesi.”

Hugo’s drawnings were collected in a book, Shadows of a Hand: The Drawings of Victor Hugo. Here’s a favorite from those pages.

I get sucked into this strange octopus. It’s so compelling! Dark, vivid, and textured. Just like large sections of Les Misérables.

5.

Sylvia Plath

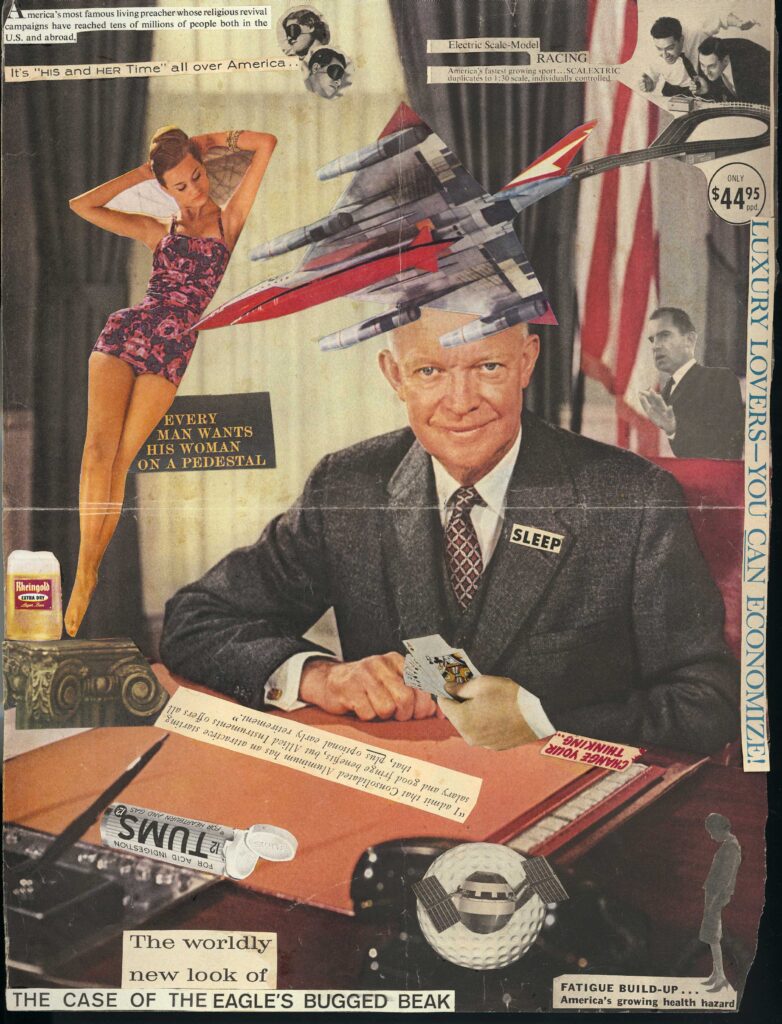

The poet Sylvia Plath actually set out to become an artist. She was an art major at Smith College, and made self-portraits, drawings, and collages throughout her life.

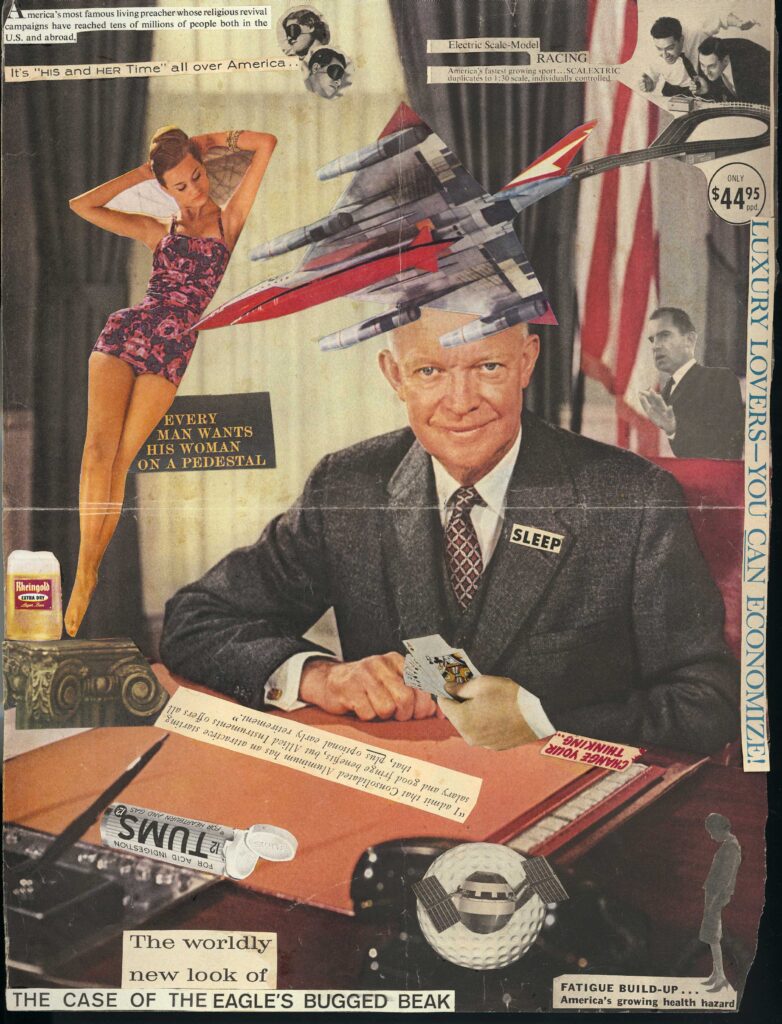

In 2018, the National Portrait Gallery dedicated an exhibit to her early work. This collage of Eisenhower (among other things) is liveliest to me.

Plath’s work is generally exuberant, if sometimes eerie. She seems to be just as interested in the uncanny at the easel as she is at the desk. But her work often features text, which feels a little like cheating, for the purposes of this very scientific exercise.

4.

Lorraine Hansberry

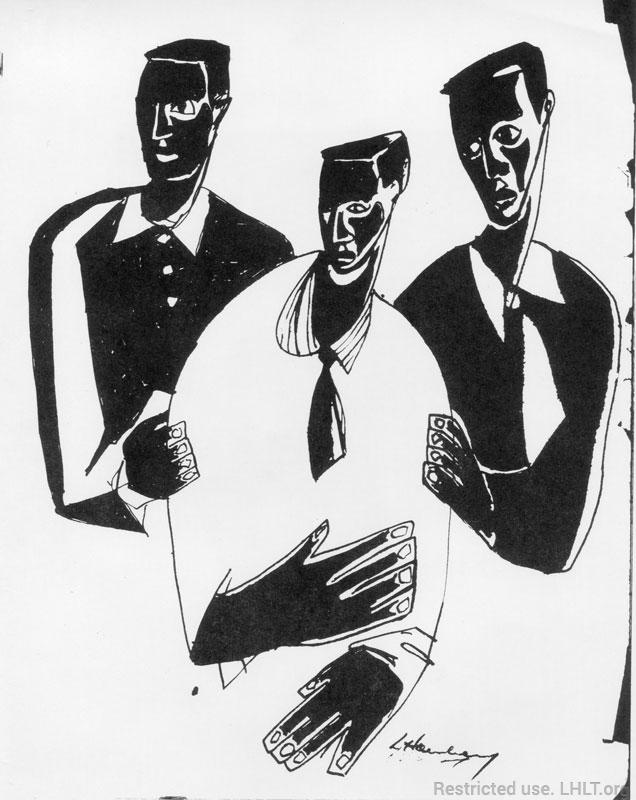

This brilliant playwright also studied drawing and painting before she ever applied her wicked wit to a typewriter. While a student at the University of Wisconsin, Hansberry produced several black and white illustrations, and self portraits running the gamut from cheeky, playful doodles to dramatic etchings.

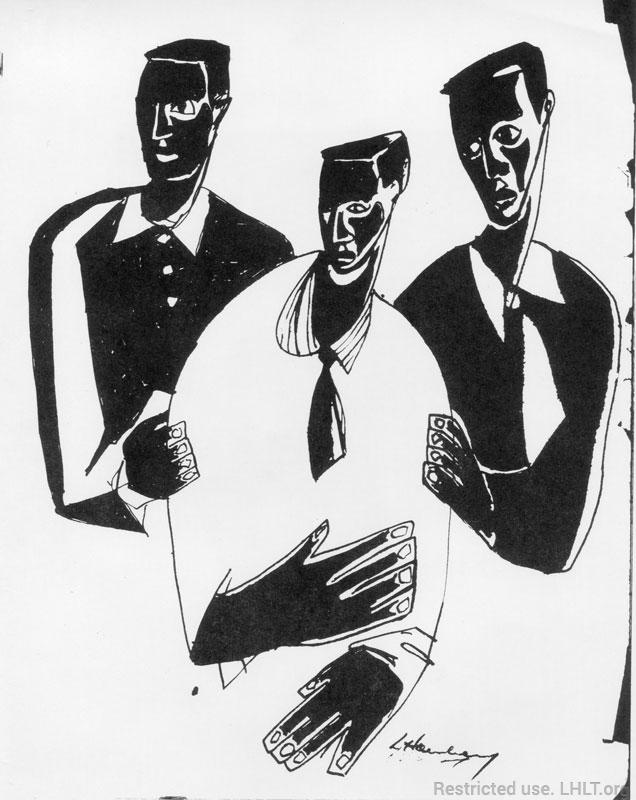

Here’s her “Three Men,” via the Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust.

I’m pretty dazzled by the shadows and shapes in this one, whose subject’s brows remind me of the famous Jean-Paule Goude print of Grace Jones. Yet another reason to mourn the early loss of this monumental talent.

3.

Tennessee Williams

Oh, Tennessee. You luminous, dramatic soul. A 2015 show at the Ogden Museum in New Orleans celebrated the Southern dramatist’s second calling.

For my money, Williams’ playful palette—as in 1976’s “Cri de Coeur,” seen above—is almost as exciting, zany, and heartbreaking as the best of his writing. And attention must be paid to this cheerful portrait of the actor Michael York.

2.

Federico García Lorca

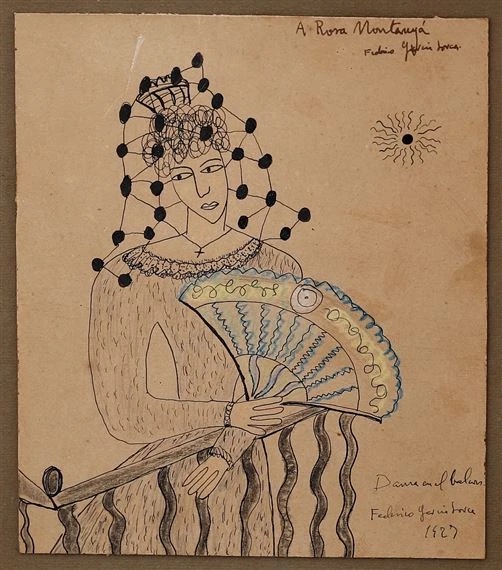

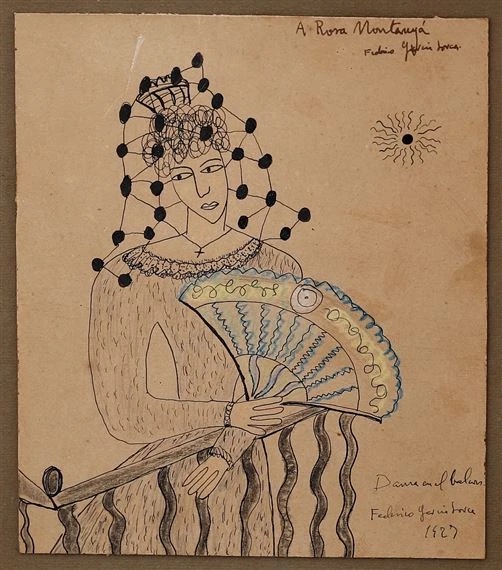

Poet and playwright Federico García Lorca was also an artist by trade. He worked in lithographs, mixed media, and good old fashioned pen and ink. I gravitate towards the drawings, which have a surrealist edge. As in 1927’s “Dama en el balcón,” pictured here.

I appreciate the subject’s whimsical tilted head, and the curious costuming. But mostly I’m drawn to the vibe creeping around the edges of his shapes. You can see where Lorca’s friendships with Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí left fingerprints.

1.

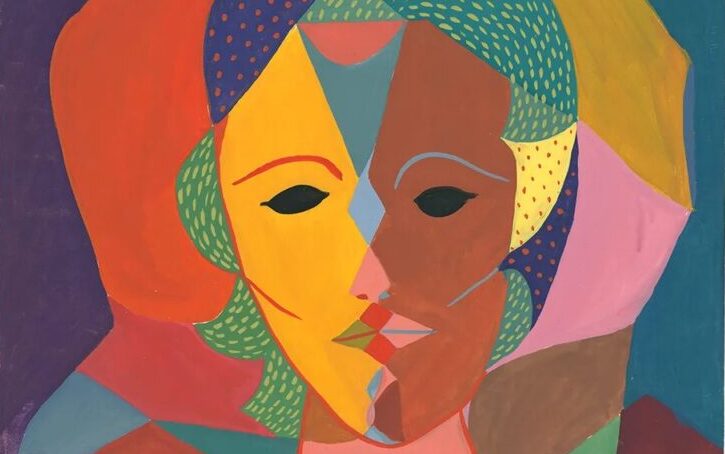

Rabindranath Tagore

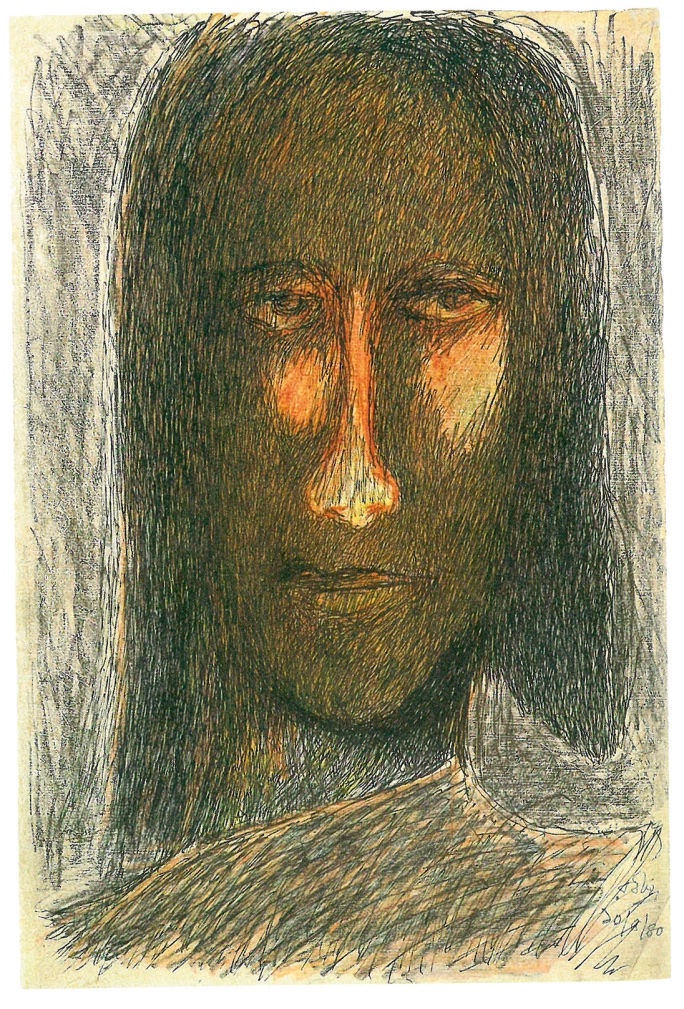

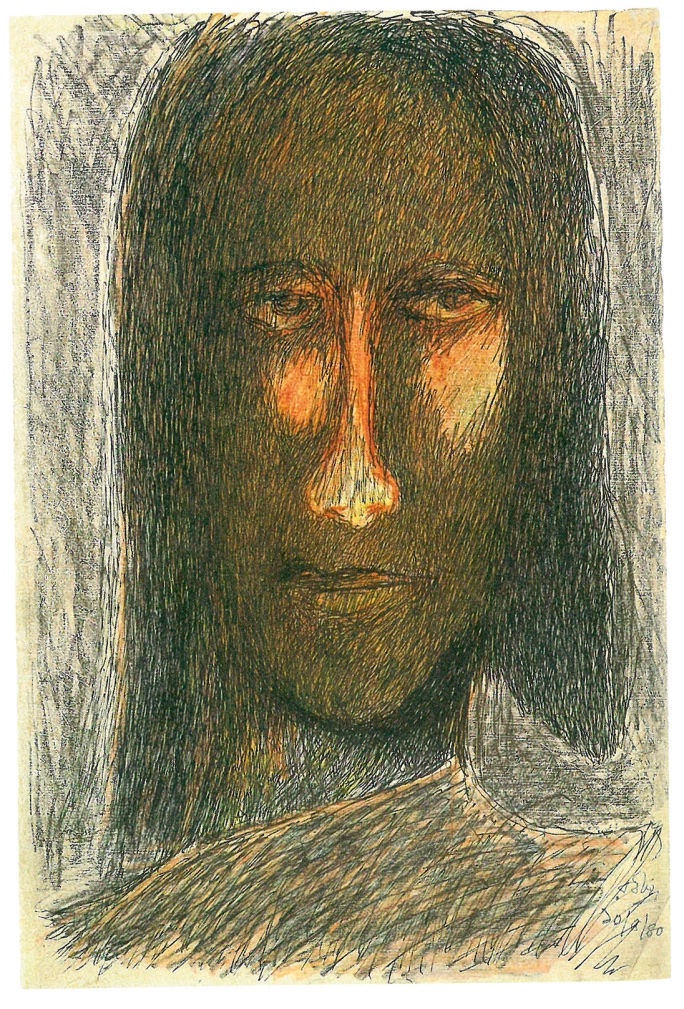

A philosopher, a painter, and a Nobel Prize-winning poet, Tagore was a true Renaissance figure. His moody, often large-scale portraits tended to depict haunted faces in extreme close up. Like this 1940 piece, “Piyali,” care of Sotheby’s.

I kind of can’t stop looking at this moody, layered, mask. It creeps and compels. It sticks to the skin, like the best poetry. So Tagore is the winner.

These visionaries make a case for the visual author, a trend that continues. In a recent Washington Post piece, the novelist Nicholson Baker described a lately-found “hankering” for painting. The novelist Raven Leilani has spoken about how her painting practice informs her work. And the author/academic/painter Nell Irvin Painter(!) has a new hybrid collection out (I Just Keep Talking: A Life in Essays) in which she investigates her own twin streams of creativity. So there’s certainly something durable to this idea of “the habit of art.”

Perhaps it’s best to judge an artist’s body of work, no matter the medium, as one continuous project. As Woolf said in her Sickert piece, “Undoubtedly the arts are closely united…Nowadays we have specialized to such an extent that critics neither hear music nor see color in literature; meaning is isolated; which accounts for the miserable state of criticism in our time and the partial manner in which it deals with its subject.”

Well-worded, Virginia. Maybe we should all be painters.

Cover image, via Smithsonian, “Triple-Face Portrait,” by Sylvia Plath.