I turned the calf-bound cover of the book with a mix of anticipation and nervousness. Would this be the volume that finally gave me the evidence I was looking for? Or would it be yet another disappointing dead-end? On the title page, I saw the now-familiar scrawled signature of Roger, 2nd Lord North, a nobleman in the court of Queen Elizabeth I.

At the top of the page, Roger had written his Latin motto, “Durum Pati” (“endure the hard path”), along with the date he’d acquired his book, 1569. It wasn’t Roger’s handwriting I was looking for, however, but the handwriting of his brother—the 16th century courtier and translator, Sir Thomas North.

I was in the reading room of Harvard University’s Houghton Library in October 2021, a KF94 mask on my face, just after the rare-book library had reopened from the pandemic. A half-dozen researchers were scattered around me at the long wooden tables examining books and manuscripts supported in foam cradles, similarly searching for literary treasure.

Not for the first time, I wondered how I had gotten to this point. A longtime investigative journalist, I had published a book six months earlier called North by Shakespeare: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest for the Truth Behind the Bard’s Work. It profiles Dennis McCarthy, a 57-year-old polymath who has for years been obsessively trying to prove that William Shakespeare had based many of his plays on now-lost plays by Thomas North.

I know. I was skeptical too when I first heard his theory, thinking it another conspiracy theory claiming Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare. As he showed me his evidence, however, I became intrigued by the idea. As it turns out, Elizabethan scribblers were constantly stealing and rewriting each other’s work, and even mainstream scholars believe William Shakespeare often rewrote earlier, now-lost plays to create his own. Among other plays, they’ve identified references to early versions of Romeo and Juliet, The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, and even Hamlet in various courtiers’ diaries, satirical pamphlets, and revels records.

But academics have been curiously uninterested in trying to ferret out the identity of the playwrights who penned those works. McCarthy had used some novel techniques to reach his conclusion that the author of a great many of them was Sir Thomas North, a writer 30 years older than Shakespeare who was best-known for the English translation of the book Plutarch’s Lives (the undisputed source for Shakespeare’s Roman plays) as well as several other books of courtly wisdom.

McCarthy used plagiarism software to compare the text of North’s translations—about a million words in all—with the text of Shakespeare’s plays—another million words. When he did, his computer lit up like a Christmas tree, displaying thousands of phrases in common, many found in similar situations and contexts, and many unique in English. Some were up to eight words long, the equivalent of hitting every number in a Powerball ticket and then some.

There was other compelling evidence as well. McCarthy and his collaborator June Schlueter, a professor emerita at Lafayette College, found a manuscript once in the North family library at Kirtling Hall that they identified as a source for 11 of Shakespeare’s plays. They discovered a handwritten journal North had made on a trip to Italy that seemed to inspire scenes from Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale, including details of locations Shakespeare never visited and scenes he never witnessed. They even discovered financial records suggesting North had been paid for plays along with the actors of the Earl of Leicester’s Men, a theater company with members in common with Shakespeare’s troupe.

Despite the potential bombshell of these findings, McCarthy had a problem—he was not a trained academic, never mind a Shakespearean scholar. In fact, he had dropped out of college at the University of Buffalo years ago, a few credits shy of graduation. Though he was a naturally gifted writer, who had published a book on the geography of evolution with Oxford University Press, he faced an uphill battle in getting any academic to take his work seriously.

I found the treasure-hunting aspect thrilling, knowing that in any of these old books might be the key to solve a mystery that has haunted Shakespeare’s legacy for centuries.Enlisting Schlueter helped. The two wrote a book together about the North family manuscript, and another book about the travel journal, each time passing peer review and winning endorsements for their scholarship. But no academic press would publish a book on McCarthy’s larger idea that North was the author of now-lost plays that Shakespeare rewrote as his own. It was too close to saying that Shakespeare didn’t write Shakespeare, or at least he wasn’t he singular genius he’s been made out to be for hundreds of years. At every turn, skeptical scholars asked, if North was a playwright, why hadn’t any of his contemporaries identified him as one? And where were his plays anyway?

That’s what brought me to Harvard on chilly fall day last year. I had now spent years writing about McCarthy’s theories, first in a front-page story for The New York Times, and then in my book. During that time, I had done my best as a journalist to keep him at arm’s length, asking probing questions and giving critics their due. My goal, I told myself, was to investigate the evidence, bring his views to light in an entertaining way, and allow the reader to make up their own mind about whether not they were true. And along the way, I’d ask some questions myself about what it takes to change hearts and minds with challenging new ideas.

As we traced Thomas North’s journeys across England, France, and Italy, however, I felt my impartiality starting to crumble. There were just too many coincidences pointing to North’s authorship of the source plays—too many characters and ideas in North’s work and people and events in his own life that seemed to make their way into the Shakespeare canon. I started openly asking myself whether I had just swallowed McCarthy’s Northern Kool-Aid, and was suffering from confirmation bias, seeing North’s life in the plays the way someone else might see the life of Sir Francis Bacon or the Earl of Oxford.

My objectivity faltered even more when I started doing my own research in the archives at the British Library and the Bodleian at Oxford, finding historical documents that McCarthy hadn’t even seen that seemed to support his theories. By far the most convincing piece of evidence for me came in North’s own handwriting. In his own copy of his translation of the book The Dial of Princes, which I examined at Cambridge University Library, North had written dozens of annotations in the margins. Many uncannily seemed to reference Shakespeare’s Macbeth, including the life of a “wicked man compared to a candle” (“Out, brief candle!”); and one even alluded to Shakespeare’s most famous stage direction, “Exit, pursued by a bear.”

Even so, I maintained my skepticism to the end, leaving it to the reader to decide what they thought of McCarthy’s audacious claims. When my book was published last March, that should have been the end of it—outside of a publicity tour to promote the book (virtual due to COVID), I should have been ready to move onto a new project. Instead, as I talked about my book to audiences, I felt a lingering frustration that I wasn’t able to say definitively whether Shakespeare did indeed adapt earlier plays by Sir Thomas North into his own.

Even as I started working on other articles, I ended up spending much of my time continuing to look through the documents I had photographed in the archives, to see if there was something I missed that might settle the matter on one side or the other.

I knew that there was little chance we’d ever find a manuscript of one of Sir Thomas’ lost plays—of the 3,000 or so plays written during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, only about 10 percent have survived. (We don’t have any manuscripts from Shakespeare either.) Still, I thought, we had one of Thomas North’s books, complete with his own handwriting seeming to reference Shakespearean plays. What were the chances that there were others?

I began searching online for auction catalogs from various sales from North family properties over the years, and then visited the Grolier Club in New York, a private club that has a library of rare book catalogs stretching back centuries. Whenever I found a book that would have existed during Thomas North’s lifetime, I added it to a spreadsheet, making special note of known sources for Shakespeare. The fate of Shakespeare’s library has always been an open question—Shakespeare famously left no books in his will. Yet, my growing list of North family books included dozens of Shakespearean sources, including the English histories of Holinshed and Hall, Italian authors such as Ariosto and Cinthio, and poets Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser.

At the same time, I searched online library catalogs in the United States and the United Kingdom for names of various generations of the North family who may have signed the cover pages or inserted their bookplates into volumes, as well as variations of “Kirtling” and “Wroxton”—the family’s manors—and Roger’s motto “Durum Pati.” I spent hours on my project, meticulously transcribing authors, titles, dates, and publishers into my spreadsheet, and eventually creating a database online.

At times, I questioned whether this was really worth doing at all—or if I shouldn’t just turn the page from Shakespeare and start work on a new project. But at the same time, I found the treasure-hunting aspect thrilling, knowing that in any of these old books might be the key to solve a mystery that has haunted Shakespeare’s legacy for centuries.

When I found a book with North family provenance, I contacted the library asking for photos any marginalia inside; as the world began reopening from the pandemic, I started visiting libraries myself, starting with Harvard and the New York Public Library, and eventually traveling to the UK to revisit the British Library and the Bodleian. The vast majority of the books I examined contained no marginalia at all. Several books, however, contained Thomas’ handwriting, in the same distinctive italic script as in his book at Cambridge.

One of them, an earlier edition of The Dial of Princes at the U.S. Library of Congress marked passages on death that McCarthy’s software had already identified as a possible source for Hamlet’s famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy. Had he marked it for his earlier version of the play? North’s signature and annotations also appeared in an Italian book at the Bodleian that is known source for Othello and Measure for Measure. Maddeningly, the library only had the first volume, not the second volume that contained the stories upon which the plays were based. An astrological book at Harvard contains notes in North’s handwriting about a rare astrological phenomenon that is also mentioned in Henry IV, Part 2.

By far the most significant book I found, however, was the calf-bound book I was examining at Harvard last October—a 1533 copy of Fabyan’s Chronicles. Written by Robert Fabyan, it is a compendium of English history that predates the more familiar Shakespearean sources of Holinshed and Hall. As I turned the pages, I found it full of Thomas North’s marginalia.

I turned excitedly to the reigns of the various Henrys and the Richards to see if North had noted anything included in Shakespeare’s history plays, but was disappointed to find that he had written little on any of those pages. In fact, he seems to have almost exclusively marked the early chapters of the book on Britain’s Roman-era history. I sent the images to McCarthy telling him that I didn’t think there was much here. He wrote me however to say: “It’s all Cymbeline.”

Now, I’d never read Shakespeare’s Cymbeline (and for good reason, as it’s not one of his better plays). The play is set in Britain during Roman times, as Rome is fighting with Britain over the question of paying tribute. Eventually Rome invades the island and is repulsed by a force led by King Cymbeline’s sons Arviragus and Guiderius. None of it is real history; rather, it’s a conflation of a number of historical events from the chronicles.

But McCarthy began excitedly showing me that nearly every one of North’s notes referred to characters and events from the play. In some cases, the language itself was even the same, as when North and Shakespeare both write that Britain paid to Rome “yearly three thousand pounds.” North even writes the name of a British king Cassibelan as “Cassibulan,” a misspelling found nowhere else but Shakespeare’s First Folio.

There are other common elements as well: Both reference a plot by one character to kill a rival by dressing up in his enemy’s clothes; both refer to a battle fought in Scotland by a wall of turfs more than 100 years later; and North even skips 200 pages to make a note about a deathbed vision by English king Edward the Confessor that also shows up in a dream sequence in Cymbeline.

In all, North made more than 50 annotations in the book, and half of them refer clearly to events and characters in the play (and many of the others seem to relate to it more obliquely). The kicker is that Thomas North died around 1604, but the first recorded performance of Cymbeline isn’t until 1610, so he couldn’t have seen the play and written notes in the family Fabyan.

Perhaps Shakespeare somehow found the book, read North’s posthumous marginalia and decided to construct a play out of the strange collection of historical notes. Any writer, however, knows how difficult it is to write a story based on someone else’s notes. Another possibility is that this is yet one more piece of evidence lending credence to McCarthy’s theory, demonstrating that North was making notes for his own play about King Cymbeline, that Shakespeare acquired and adapted years after his death.

I know which explanation I favor. As I heard McCarthy’s account of the marginalia, my last doubts fell away, and I realized that I was no longer a skeptical observer of the Northern hypothesis of Shakespeare authorship; I had become a collaborator. I had gone in with an idea that if North wrote early versions of Shakespeare’s plays, there would be books with his notes that demonstrated his playwriting process—and here, I had found one that seemed to show just that. There is no way that I could be that lucky, I told myself. In the face of such evidence, I could no longer maintain any doubt.

McCarthy wrote a paper about the “Cymbeline discovery,” which received coverage this April in The Observer, the Sunday newsmagazine of The Guardian newspaper. Not surprisingly, the story included skeptical comments made by Shakespearean scholars who hold fast to the notion of Shakespeare as a singular genius. But I still have more than a hundred more books once owned by the North family in my database. More than forty are at Washington DC’s Folger Shakespeare Library, which has been closed due for renovations, its collection locked away until 2023. The others, I am convinced, are scattered throughout the world’s libraries and rare-book collections. What are the chances that some of them also have Thomas North’s annotations, and that they also relate to Shakespeare’s plays? I know now that I am determined to find out.

____________________________________

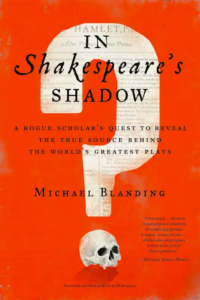

In Shakespeare’s Shadow: A Rogue Scholar’s Quest to Reveal the True Source Behind the World’s Greatest Plays by Michael Blanding is available now via Hachette.