The village of Hubyn was never officially evacuated—but over the last 30 years so many people have left that the effect is the same. Of a few dozen houses, most stand empty. A single multipurpose shop caters to an aging population. Plastic flowers adorn a Soviet war memorial engraved with symbols no longer tolerated in Kyiv. The road that once connected Hubyn to its local municipal town—Chernobyl—was blocked three decades ago, when the border of the Exclusion Zone was drawn along the village’s northern edge.

We drive into Hubyn in the middle of the afternoon. Two old men sit on a bench, and a handful of women wearing shawls plod along the main street, their footsteps synchronized with the rhythm of the pounding industrial techno. Outside the long-abandoned village club, young Ukrainians in dreadlocks and neon rave gear drink beers and share a joint as they wait for the party to begin.

Town sign, Chernobyl. In the Soviet era it was common for towns and villages to erect their own idiosyncratic “welcome” signs. Alongside a hammer and sickle are various symbols representing the river port, industry, and the nearby nuclear power plant.

Town sign, Chernobyl. In the Soviet era it was common for towns and villages to erect their own idiosyncratic “welcome” signs. Alongside a hammer and sickle are various symbols representing the river port, industry, and the nearby nuclear power plant.

The rave in Hubyn is the brainchild of Igor Oprya. For several weeks he and a team of volunteers have been sweeping debris into piles inside the old club building to make space for dance floors and a bar. The promotion of the event was controversial: an online video clip showed a masked man daubing paint in rainbow colors over the town sign in Pripyat’s Microdistrict 4, with a caption that read: “I Invite Everyone to Chernobyl Future Rave.”

Some stalkers were outraged at what they considered to be a desecration of the Zone. I spoke to Stepan, one of a number of stalkers who smuggled in pots of grey paint to return the sign to its original condition. “These people call themselves AVO,” he told me. Anarkho-Vandalskyy Otryad AVO’s social-media feed describes the project as “performance art theatre,” and calls for the decommunisation of Pripyat. A previous rave they held in the Zone was named “Tripyat,” and their next event, “Chillnobyl,” was only a week away. I was curious to know how AVO justified their interventions in the Zone and it seemed the best way of finding out would be to go along to the rave and ask them.

By dusk the village club is crowded and notch by notch the music gets louder. A local woman in her mid-fifties approaches the hall. I assume she’s come to complain, but instead she begins introducing herself to the partygoers. We talk. Her name is Valya and she lived in Donetsk, but came to stay with her family in Hubyn when conflict broke out in east Ukraine. She’s reluctant to talk about the war, so instead I ask her what she thinks of the rave. “Wonderful,” she says. “Hubyn is mostly abandoned. It’s a sad place. When they closed the Zone it became a dead end. It’s good to see young people here!” Before the party kicks off, a film is projected onto a wall once hung with noticeboards and decorated with portraits of Soviet leaders. Valya fetches two elderly female neighbors from the village and together we watch the documentary The Babushkas of Chernobyl (2015).

Village club, Hubyn. In September 2019, this long-abandoned building on the border of the Exclusion Zone was rejuvenated as the venue for an illegal techno rave.

Village club, Hubyn. In September 2019, this long-abandoned building on the border of the Exclusion Zone was rejuvenated as the venue for an illegal techno rave.

By nightfall the dance floor is manic. Pumped-up ravers in neon costumes swing glow sticks and blow whistles. By 10 pm one partygoer has already passed out on a sofa, and after his friends help him outside, he promptly staggers back in and collapses again in the same place. People gather around fires on the lawn outside; stray sparks and cannabis smoke hang in the air as local babushkas drift in and out of the crowds. I buy a “Black Stalker” (whiskey and cola) at the surprisingly well-stocked bar and take it outside, where I get chatting to a techno DJ waiting for his early-morning slot.

“Techno is pure emotion,” he says, between swigs of an energy drink. “The most honest of all musical genres.” I ask him who these partygoers are—stalkers, or ravers? He gazes at the crowd for a moment. “Some stalkers, I think, but a lot of these people I know. It’s like the Kyiv rave scene, taking over the Zone. I thought it was strange at first, when they asked me to play here. But then I thought, why not? Chernobyl is ours, it’s our history. I think it’s good to bring life back here, to express new emotions in this place.”

Stalker tour operator Vladyslav Suvorow arrives around midnight. He’s fresh from an illegal hike—and apparently it was a total disaster. It had rained heavily all day, soaking their party of eight to the skin and turning the soil into slippery mud. After ten kilometers they gave up, deciding to surrender themselves to the police for an easy lift back to the checkpoint. But one of the tourists had no passport, which would have meant lengthy questioning by the border guards. So Vladyslav stayed with him, and the two of them walked for another nine hours through the rain to get safely out of the Zone. My own stalker guide, Kirill, arrives a little later, though I almost don’t recognize him. Last year he had been a teetotal, contemplative sort, who seemed more at ease in the Red Forest than around other humans. But tonight Kirill is a celebrity—everyone at the rave seems to know him, and he shouts, swaggers, dances, and drinks his way through the crowds. When I say hello, he greets me warmly—but he isn’t in any state for conversation.

The only sober person in the hall seems to be the rave’s organizer, Igor. He’s constantly on the move. Now he’s rushing from an electrical failure in the second sound system, to tend to a passed-out drunk in the garden. It isn’t until some time in the early hours that I manage to pin him down for a chat.

Perimeter fence, Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Behind the village of Hubyn, rusted barbed wire hangs across a footpath leading into the Zone. From this location, a trespasser would have to walk for a full day before encountering significant levels of radiation.

Perimeter fence, Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Behind the village of Hubyn, rusted barbed wire hangs across a footpath leading into the Zone. From this location, a trespasser would have to walk for a full day before encountering significant levels of radiation.

“A lot of people here have never been to Chernobyl before. We are trying to draw attention with our performances in the Zone—even if it’s negative attention.” Igor, whose interest in the Zone was partly inspired by the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. games, says he has made more than thirty illegal visits since 2012. He worked briefly as a waiter at one of the hotels in Chornobyl, and it was while talking to tourists there that he became concerned about the nature of the industry. “I am not against tourism—I’m pro-tourism. But official tourism in the Zone today is vicious and corrupt. All the tour companies pay into a criminal kickback scheme, when really the money should be going to the national budget.”

Igor says his group, AVO, provides a protest movement. “It’s a virtual counter-subculture,’ he says. ‘It started in 2010 as a joke. Our mission today is to transform Pripyat—not destroy it as some are saying, but to use performance to bring attention to it. Okay, so we painted a sign… so what?” No one got hurt, and already it has been painted back to its original color. There’s a Soviet crest on top of a building… by law it must now be removed. So how about instead we paint it pretty pink? Ukraine’s decommunization law is absurd, and this is how we answer it—with absurdity, with post-irony.’

Crane claw, Yaniv (Pripyat outskirts). This piece of equipment was used to clean debris from Reactor Block 4 during the 1986 clean-up. Today it gives a potentially dangerous dosimeter reading of up to 600 μSv/h. In late 2019, it became the target of purported ‘performance art’ and was painted bright pink. This began an ongoing battle between graffiti artists and the purist stalkers who would attempt to restore its original colors.

Crane claw, Yaniv (Pripyat outskirts). This piece of equipment was used to clean debris from Reactor Block 4 during the 1986 clean-up. Today it gives a potentially dangerous dosimeter reading of up to 600 μSv/h. In late 2019, it became the target of purported ‘performance art’ and was painted bright pink. This began an ongoing battle between graffiti artists and the purist stalkers who would attempt to restore its original colors.

A few weeks later, AVO’s next stunt is to paint Chernobyl’s famous abandoned crane claw bright pink. A highly irradiated object, it isn’t as easy to restore as previous targets were. Online, Igor writes: “On the outskirts of the city of Tripyat there is a crane claw that was used to scoop up the Chernobyl reactor debris… Now tourists will be less likely to endanger their health, because they will no longer photograph themselves in front of this beauty.”

I sleep in a friend’s car, waking at dawn to the ceaseless drumbeats. A handful of zombies are still dancing in the hall. Some huddle in corners or sleep in tents pitched in storerooms, while others sit outside, smoking cigarettes and staring blank-faced into the embers of last night’s fires. Behind the village club, the old road, its tarmac edges overgrown with grass, leads north towards the forest. I follow it past the graveyard with its war memorial, until it stops abruptly where the earth has been bulldozed into a ridge marking the outer border of the Exclusion Zone.

Mural on a residential building, Heroes of Stalingrad Street, Pripyat. This Socialist-realist mural depicts virtuous citizens (a farmer, a construction worker, a police officer, and a Young Pioneer) under a radiant Soviet crest.

Mural on a residential building, Heroes of Stalingrad Street, Pripyat. This Socialist-realist mural depicts virtuous citizens (a farmer, a construction worker, a police officer, and a Young Pioneer) under a radiant Soviet crest.

The “Bridge of Death,” on the road between Pripyat and the power plant. It is claimed that on the night of the disaster a number of Pripyat residents stood here to get a better view of the burning plant. The bridge derived its nickname from the widespread—but incorrect—belief that all the spectators died soon afterwards from radiation exposure.

The “Bridge of Death,” on the road between Pripyat and the power plant. It is claimed that on the night of the disaster a number of Pripyat residents stood here to get a better view of the burning plant. The bridge derived its nickname from the widespread—but incorrect—belief that all the spectators died soon afterwards from radiation exposure.

A few rusted strands of wire swing lazily between the trees. Distant electronic beats pound through the forest, shaking dewdrops from the pines. High above, a woodpecker responds with its own staccato counter-rhythm as I step into the Zone. Inhaling deeply, I feel a tremendous sense of freedom—a vast and complex terrain stretches before me, where nature thrives untamed, and those who remain submit themselves to its mercy. Strange utopian art from the old regime lies waiting to be discovered beneath the trees and steel giants—towering technological wonders of the Cold War era—rise up like rusted guardians over this timeless no-man’s land. As I walk into the sentient forests of Chernobyl, I hear the words of Tarkovsky’s Stalker:

“Everything is already taken from me, there, on the other side of the barbed wire. All I have is here. Can you understand?! Here! In the Zone! My happiness, my freedom, my dignity—everything’s here!”

_________________________________________________________

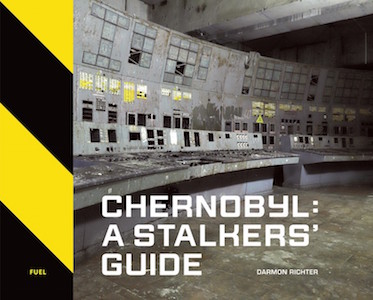

From Chernobyl: A Stalkers’ Guide by Darmon Richter. Used with the permission of FUEL Publishing. Copyright © 2020 by Darmon Richter.